The Gethsemane crisis: Why didn't Jesus want to die?

One of the most challenging stories of Scripture is when Christ kneels in despair at Gethsemane, and asks that he should not face the cross. Its familiarity can dull us to its strangeness. Without the cross there could be no salvation, so why didn't the Son of God want to die?

Mark's Gospel (14:32-36) says: 'They went to a place called Gethsemane, and Jesus said to his disciples, "Sit here while I pray." He took Peter, James and John along with him, and he began to be deeply distressed and troubled. "My soul is overwhelmed with sorrow to the point of death," he said to them. "Stay here and keep watch."

'Going a little farther, he fell to the ground and prayed that if possible the hour might pass from him."Abba, Father," he said, "everything is possible for you. Take this cup from me. Yet not what I will, but what you will."'

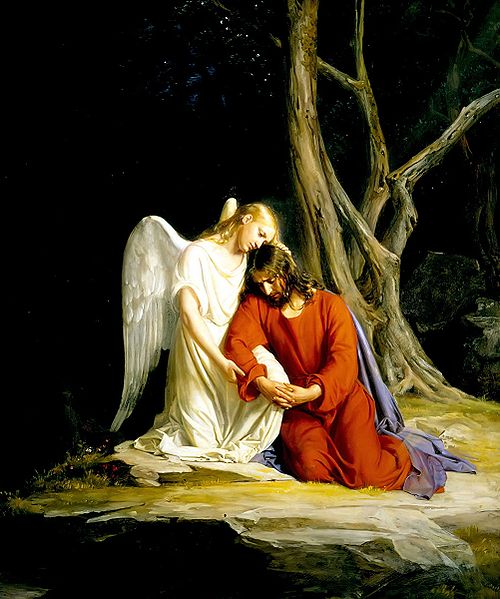

Jesus repeats this prayer twice after, and in Luke's account we read of an 'agony' so great that 'His sweat became like drops of blood, falling down upon the ground', and that an angel came to strengthen him (Luke 22:39-46).

Agony is an appropriate description of the moment; this is not a scene of serenity, of Christ peacefully coming to terms with his death. It is not even that he laments the pain of death while accepting that it's part of the plan. He explicitly asks God, for whom anything is possible, to 'take this cup from me'. This cup harks back to 'the cup that I am going to drink' earlier mentioned by Jesus (Matthew 20:22), itself a reference to the 'cup of wrath' in the Old Testament, a vivid metaphor for God's righteous judgment (Jeremiah 25:15, Isaiah 51:17). The cup for Jesus is the cross, and he doesn't want it.

It's a story that has inspired many, showing a highly relatable, human Jesus who struggles with mortality and the reality of pain and suffering. The crucifixion will be of great cost to Christ. It is a prospect that psychologically haunts him. But since Christians believe Christ was fully human and fully divine, that latter nature must surely be present too – the Son of God is doubting the mission for which he was sent.

Some theologians have simply said that Christ only experienced weakness and suffering in regard to his human nature, others have found this unsatisfying or problematic.

So was Jesus ambivalent about the plan to save humanity? Was he frankly keen to avoid it if he could? For the Gospel writers, these are scandalous words to put in the mouth of your saviour. Yet three of them did just that.

Gethsemane certainly makes for engaging drama and impressive art. In the recent film Mary Magdalene Joaquin Phoenix portrays Christ with a focus on his vulnerability and weakness. When he performs miracles it drains him; at times he seems to pass out in public.In the film's version of the resurrection of Lazarus, Christ weeps, but here only after Lazarus has been raised. His tears appear to be for himself: this man's death gives him horrifying premonitions of his own imminent demise.

Giovanni Bellini's painting Agony in the Garden gives a stunning portrayal of the Gethsemane event, with Christ surrounded by numerous winding pathways and two horizons, one painted in light, the other in darkness. It offers a reflection on human agency: Christ has a choice of which path to take. Close to the viewer we see a swinging gate door that offers an easy escape from Judas and the Roman guards approaching in the background. Will he stay, or will he go? When we speak of a state of 'agony' today, we frequently imply just this kind of crisis of judgment, an internal wrestling about which path to take. We're reminded by Bellini that Christ had a choice.

Jesus tells his father 'everything is possible for you', but in a sense, everything was possible for Jesus too. He could have run away. He could have summoned angels and wiped out his opponents. We know what happened ultimately, but our understanding is amplified when we recognise it was a free choice. A choice which was paradoxically not the imposition of will, but the relinquishing of it to divine purposes.

Christian orthodoxy has long struggled with putting the incarnation into words without undermining or doing damage to it. There is the danger, for example, of speaking about the God who became flesh in such a way that Jesus was never properly human or not quite divine. One runs the risk of an anti-trinitarian heresy by breaking up the will of the Father and Son, as though they had conflicting goals.

With a paradox like Gethsemane, human words probably get in the way: this isn't an event demanding a theological treatise or an easy 'explanation'. It is a deeply emotional encounter, Jesus embracing his Father with an honesty that we might share with our own parents. Humanity is thus offered a glimpse into the life of the godhead, of divine love and a divine will to suffer and save, related to the human fear and agony that we know so well. We might not 'get it'. But we can see it, relate to it, bow before it. Gethsemane could have gone another way, and yet for our sake, it didn't.

Jesus prays a radical prayer that human beings who follow him are invited to make their own, in the face of whatever anxieties may befall them in their own agonies: 'Yet not my will, but yours be done.'