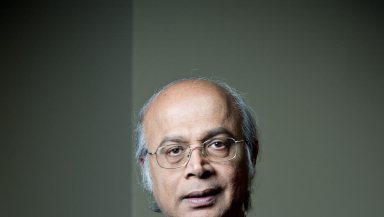

It has been announced that Michael Nazir-Ali, former Bishop of Rochester, has left Anglicanism and become a Roman Catholic.

He was received into full communion with the Roman Catholic Church, entering the ordinariate on his name day, the feast of St Michael, two weeks ago.

This is without doubt one of the most politically and theologically significant changes of allegiance in the Christian world for some time.

There have been a number of high-profile conversions including a former Bishop of London. So why should that of Michael be so nuclear in ecclesiastical and political life?

The answer is that he formed the centre of a nucleus of evangelical resistance to the slippage in the secular progressive accommodation embarked on by the Anglican Church. He was particularly outspoken on the serious consequences of ignoring the implications of the growth of Islam, and the importance of the Christian definition of marriage being restricted to a man and a woman with the intention of having children.

Previous high-profile Episcopal conversions were mainly of Anglo-Catholics. It was almost expected of them. Others shrugged their shoulders and passed them off as almost inevitable and of no great surprise or perhaps even of no great significance.

But Nazir-Ali is different. The route by which he came to prominence, which included holding the post of General Secretary of the Church Missionary Society, was evangelical. And of course evangelicalism is usually uncompromisingly hostile to Catholicism.

The whole of Western culture is reeling under a kind of civil war. It amounts almost to a form of cultural and spiritual nervous breakdown. All organisations are creaking at the seams under the assault of what is variously called progressive, politically correct, woke or cultural Marxism.

The Church has been creaking more than most since the fault lines are theological and spiritual as well as philosophical and political.

Anglicanism's global movement of conservative protest, 'GAFCON', was largely led by Michael Nazir-Ali. His articulate and well-informed theological voice acted like a glue to hold together disparate orthodox actions across the Anglican world. His influence provided much of the driving force that both propelled and held together the conservative or orthodox Anglican revolt against the progressive revolution led by the American Episcopal Church and followed by Archbishop Justin Welby from Lambeth Palace.

The fact that he has turned his back on the protest movement he helped to create has enormous significance for two reasons in particular.

Firstly, it is an indication that Nazir-Ali has, like others who have converted recently to the Catholic Church, judged that the schism in the Church rooted in the Reformation has run out of steam. The Church is no longer realistically divided by the arguments that erupted five hundred years ago driven by the Reformers. These conflicts have been replaced by a fresh but no less significant cultural and philosophical realignment.

This struggle has coalesced into one between the remnants of Christendom and a fresh wave in the assault of secularism by (cultural) Marxism. They represent two utopian visions, one spiritual and the other political, in direct conflict.

Secondly, in Nazir-Ali's judgement, Anglicanism has been so compromised by the forces of progressive secularism that it cannot now be rescued.

The implications of this will shake Anglicans throughout the worldwide Communion.

The conservative GAFCON movement that Nazir-Ali had helped create and lead was set up to defend Anglicanism against being subverted by progressive values.

It intended to draw together a variety of Anglican provinces that were reluctant to allow their understanding of the Bible's teaching on gender and sexuality to be challenged and subverted by political and cultural assaults that they judged to be sub or anti-Christian. But within this protest movement there was no unity across the spectrum of views on the two major controversies that emerged over feminism and homosexuality.

GAFCON embodied the laudable Anglican ambition for compromise, but the chasm it tried to bridge proved too wide and too problematic.

Some of the critics of the secularisation of Christianity had identified feminism as threatening a fatal assault on the biblical revelation of God's fatherhood. They asserted that the movement for the ordination of women carried with it the weapons of relativism, a reliance on secularism and a psychological and political antipathy to patriarchy that made the experience of the 'fatherhood of God' inaccessible. They resisted it in fidelity to the Bible and the tradition of the Church.

Unable to reach a common mind on this, GAFCON was at least able to agree a moratorium on the issue of women bishops. And so the civil war that feminism had given rise to could be largely postponed.

But recently that moratorium had been broken by the progressives in the movement who were unable or unwilling to keep their commitments to the moratorium. With the consecration of five women bishops in different provinces, the pretence of compromise was no longer possible.

Nor was the agreement on how to hold the line on the blessing of same-sex couples any easier to define and defend.

Only recently a high-profile church belonging to the conservative Anglican Church in North America and GAFCON transferred its allegiance to a more progressive group as it switched sides on the gay blessing issue. Neither ACNA nor GAFCON could find any theological mechanism for convincing waverers of the Christian authenticity of the conservative position.

What this crisis revealed was that Anglicanism lacked an essential tool in the struggle with secular relativism, the Magisterium.

Schism and relativism could only be avoided by relying on a collective theological and spiritual mind that had emerged flowing down through the ages to define the faith and to offer an authentic interpretation of the Church's understanding of its foundational texts.

Michael Nazir-Ali found his attempts to hold together the conservative compromise alliance foundering without this essential Catholic mechanism for defining truth and authority.

In his email to his friends explaining his decision Bishop Nazir- Ali wrote, "I believe that the Anglican desire to adhere to apostolic, patristic and conciliar teaching can now best be maintained in the (Catholic) Ordinariate."

This sentence represents a condensed code which needs to be unpacked to be understood.

In this code he communicates his judgement that Anglicanism can no longer be trusted to maintain its links with the historic mind of the Church.

'Apostolic' means the preferencing of the early Church's interpretation of the biblical texts to those of contemporary culture.

'Patristic' references the prioritising of the judgements and theological values of the first five centuries where they differ with the judgements of the last five centuries.

'Conciliar' refers to the authority of the early Ecumenical Councils of the united Church before the schism of 1054. The 39 Articles of the Church of England insist that some of the decisions of these Councils were flawed. Nazir-Ali is repudiating that and accepting the view of Catholicism and Orthodoxy in defiance of Reformation protest. These Ecumenical Councils and their interpretation of biblical texts provide the heart of the Church's self-understanding and make up a foundational part of the Magisterium.

Bishop Nazir-Ali's move will also have the effect of considerably strengthening the reputation of the Ordinariate in England. Church Militant quoted an Ordinariate commentator whose view was that "Lord Nazir-Ali is the most high-profile convert from the Church of England to Rome for the last hundred years, probably since the conversion of the intellectual giant Msgr. Ronald Knox."

"Michael is one of the most prodigious intellects of our time, a heroic apologist for the faith, a bulwark against radical Islam, a laser-sharp cultural commentator, a persuasive preacher, a passionate evangelist of the highest caliber, and a brilliant linguist and poet," he wrote.

Bishop Nazir-Ali said: "My hope is that this patrimony will be able to contribute the riches of Anglican liturgy, biblical study, pastoral commitment to the community, methods of doing moral theology, hymnody and much else not only to the Ordinariate but, beyond that, to the wider Church."

Bishop Nazir-Ali's conversion to Catholicism is not just one more high profile move from what has become the periphery of Christianity to the centre.

It signals an invitation to a serious reconfiguration of those Christian individuals and organisations in a fresh alliance against a hostile secularism. It invites the wider Church to turn its back on the crisis that erupted five hundred years ago but no longer has relevance.

And perhaps most importantly it is a costly personal move to restore the unity of the Church within the Petrine and apostolic tradition that first evangelised the West.

Dr Gavin Ashenden is a former chaplain to the Queen. He blogs at Ashenden.org