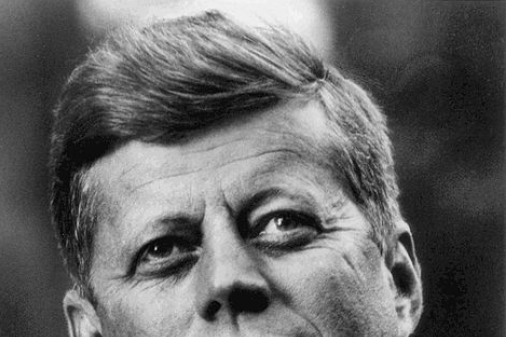

Continuing a series on the faith of America's presidents, which began with Ronald Reagan's fight for freedom, and explored the rich faith of Jimmy Carter, this week we briefly explore the faith of America's one and only Catholic President: John F. Kennedy.

JFK is a cultural icon, his image enduring beyond his presidency to an almost mythic status. His tragic assassination in 1963 left many wondering what would or could have been, had he lived on. He didn't often discuss God in public; as Biographer Thurston Clarke wrote of Kennedy, "Few presidents have been as religiously observant yet reluctant to discuss their faith."

Kennedy's faith is mysterious, but where we see it emerge, it is important and profound.

Fighting for the faith

Kennedy's status as the only Catholic President is hard to ignore. Before he won the election many doubted his chances precisely because of his Catholic faith. It deterred many in the Protestant community, without whose support a victory seemed impossible. Anti-Catholic prejudice was pervasive, so Kennedy had a tough fight when, in May 1960, he entered the West Virginia primary, where the Catholic constituency was only 4 per cent of the electorate. As the JFK Library documents:

"When the polls in West Virginia showed JFK behind by 20 points, he decided to address the issue head on in a speech before the American Society of Newspaper Editors:

'Are we going to admit to the world that a Jew can be elected Mayor of Dublin, a Protestant can be chosen Foreign Minister of France, a Muslim can be elected to the Israeli parliament—but a Catholic cannot be President of the United States? Are we going to admit to the world--worse still, are we going to admit to ourselves—that one-third of the American people is forever barred from the White House?""

Kennedy could have disowned his religion, which clearly wasn't helping him get elected, yet he stood steadfast. He won the West Virginia primary, but in September 1960 a group of 150 Protestant ministers gathered in Washington to insist that Kennedy publicly repudiate the Catholic Church's teaching as a sign of his independence from Rome. In response, Kennedy made a now famous speech to a Protestant gathering at the Greater Houston Ministerial Association. He emphasised the importance of the separation of Church and State, and how subsequently there should be no religious test for the office of the Presidency.

He said: "I believe in an America that is officially neither Catholic, Protestant nor Jewish; where no public official either requests or accepts instructions on public policy from the Pope, the National Council of Churches or any other ecclesiastical source; where no religious body seeks to impose its will directly or indirectly upon the general populace or the public acts of its officials; and where religious liberty is so indivisible that an act against one church is treated as an act against all.

"For while this year it may be a Catholic against whom the finger of suspicion is pointed, in other years it has been, and may someday be again, a Jew— or a Quaker or a Unitarian or a Baptist. It was Virginia's harassment of Baptist preachers, for example, that helped lead to Jefferson's statute of religious freedom. Today I may be the victim, but tomorrow it may be you — until the whole fabric of our harmonious society is ripped at a time of great national peril."

Kennedy wasn't just defending himself as a Catholic, but pointing to something even more profound: religious freedom in society and the opportunity to serve in office whatever your personal beliefs may be.

"Ask not what your country can do for you..."

JFK's emphasis on the division of Church and State might incline one to see faith as having little relevance to Kennedy's political life. It's true that he didn't talk about God often, but there is a rich Christian ideal underpinning his political vision, which we glimpse in his inaugural address in 1961.

The Rev. Daniel Coughlin, first Catholic chaplain in the US House of Representatives, wrote about the speech in a blog post: "The whole speech was framed by his belief in a living and ever-present God both at its beginning and in the end."

Kennedy's words: "For I have sworn before you and Almighty God the same solemn oath ... Man holds in his mortal hands the power to abolish all forms of human poverty and all forms of human life. And yet the same revolutionary beliefs for which our forebears fought are still at issue around the globe – the belief that the rights of man come not from the generosity of the state, but from the hand of God."

He then famously called Americans to "Ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country...Knowing that here on earth God's work must truly be our own."

Kennedy's iconic words were rooted in the idea of Christian participation in and for the world. As Coughlin writes: "With a Catholic perspective of humanity, personal power, the needs of the world and the priority concern for the weak and the poor, President Kennedy's words still stir the heart and imagination of America."

The Coming Storm

But Kennedy's faith would be put to to the test when he faced the tragic loss of his newborn son, Patrick. Clarke describes the raw emotion that was revealed from this normally reserved man, breaking the family tradition that "Kennedy's don't cry."

Seen in this light, the glimpses seen of Kennedy's emotional and spiritual life — at prayer, or the prayers he wrote — are important. After one tense Soviet summit he scribbled these words to himself, paraphrasing Abraham Lincoln: "I know there is a God–and I see a storm coming; If He has a place for me, I believe I am ready."

Whether it be his struggle for peace in the tension of the Cold War and the Cuban Missile Crisis, or his tragic assasination, his storm did indeed come.

In Kennedy's life we may not see fervent, public dedication to God - indeed he was perhaps "a little less convinced" than others. But he nonetheless stands out for his faith: his commitment to Catholicism despite the political cost, his struggle for peace, and the glimpses we get of a belief that grounded both his world vision, and the daily storms of his life.