The writer of the Letter to the Hebrews reminds Christians that they are surrounded by a great "cloud of witnesses." (NRSV) That "cloud" has continued to grow in size since then. In this monthly column we will be thinking about some of the people and events, over the past 2000 years that have helped make up this "cloud." People and events that have helped build the community of the Christian church as it exists today.

In 1145, a strange rumour began to circulate among Christians in Syria, and from there the report was taken to Italy and the papal court. It seems that it originated from Bishop Hugh of Gebal (now Jbail, Lebanon). The story which began with Bishop Hugh was recorded that year by Otto of Freising, Germany, in his Chronicon. There was, it seems, a mysterious event stirring in the east; and it could not have occurred at a more opportune time. At least that was how it appeared to the Christian chroniclers who first introduced to Christendom the person of "Prester John".

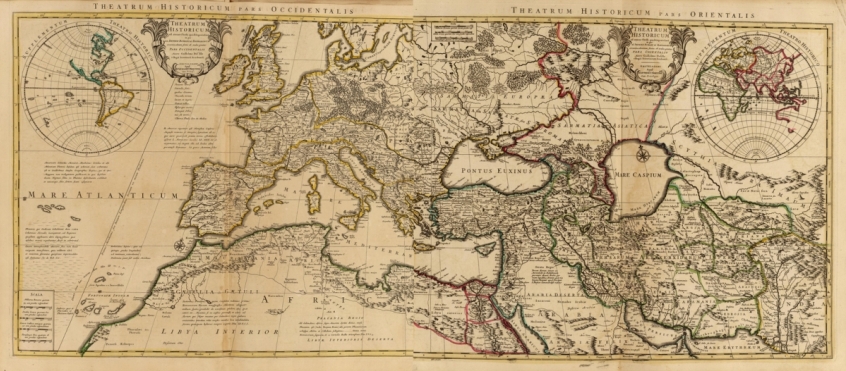

The year before (in 1144) the Muslim Seljuk Turks had captured Edessa (modern Urfa, south-eastern Turkey). The county of Edessa was one of the four crusader states which made up the Christian territories of Outremer (from the French: outre-mer, 'beyond the sea').

A Byzantine Christian city, it had been taken by Islamic forces in 1078, but had been recaptured by Christians in 1098, during the First Crusade which had gone on to seize Jerusalem in 1099. Since then, the county of Edessa, the principality of Antioch, the county of Tripoli, and the kingdom of Jerusalem had made up the crusader states in the Holy Land. Now Edessa had been lost and, in December 1145, Pope Eugenius III called for the Second Crusade to take it back and defend the crusader states. An existential conflict was brewing.

It was against this background that the strangest of rumours began to circulate. According to these reports, a mighty army was gathering in the east. It was led by a fabulously wealthy and powerful ruler who was both "priest and king", He was, the reports insisted, a direct descendant of the Magi who had visited Jesus. Like them, he was "from the East" (Matthew 2:1, NRSV). He had, it seems, defeated the Islamic king of Persia; he had then taken the Persian capital at Ecbatana; and he now intended to march to Jerusalem in support of the Christians of Outremer.

However, there was a problem. He was currently prevented from proceeding because his army was blocked by the river Tigris. If this could be crossed, then this mighty eastern Christian army would pour into the Holy Land and turn the tide of battle.

The possibility promised to be a game-changer in the troubled politics of the Middle East. The arrival of Prester John and his magnificent army was eagerly awaited, for this would surely ensure the victory of the Christian states in their battles with their Islamic rivals. There was only one drawback – Prester John did not exist.

What lay behind the story of Prester John?

The story of Prester John gives us a remarkable insight into the things medieval Christians believed existed beyond the boundaries of their familiar world. For John was, it was alleged, a king from a realm of mysterious beings and happenings. He was from an eastern world which was partly known from the tales of travellers but one filtered through imaginations rather than lived experiences. Medieval books of wonders located animals and beings there, drawn from ancient Greek and Latin texts and more recent reports. It was a land of unicorns and gryphons. One manuscript, tellingly titled "Marvels of the East", carried reports of lands where bearded women hunting with tigers, dogs with tusks breathed fire, and half-human-half-donkeys lived. The "East" was where anything was possible. And to the medieval cosmographer, the "East" could combine Ethiopia with India (and beyond), since some of the details of actual geography were far from settled.

This fabulous land was clearly rooted in a medieval worldview, but also tapped into deeper areas of the human psyche. After all, in the twenty-first century the most extraordinary things still circulate on social media and among conspiracy theorists. The human capacity for combining sober judgement with imaginative credulity it still with us. It was not just a medieval phenomenon.

Nevertheless, there is more to the story of Prester John than wishful thinking about a rescuer who hailed from an eastern never-never-land. Bishop Hugh, the apparent originator of the report, probably had heard of a battle which had occurred in 1141 in Persia. For in that year the Islamic Seljuq sultan had indeed suffered a serious defeat. However, it was at the hands of the Mongol khan who ruled the Karakitai empire in Central Asia. The rulers of this empire were Mongol-Buddhists. But this is where the story really gets interesting. A very large minority of this Central Asian Buddhist empire were Christians!

These were so-called "Nestorians" and their community is now often unknown among modern Christians. They differed from many other Christians regarding the understanding of how the divine and human nature of Christ was combined. Communities of Nestorian Christians existed in Persia, India and as far away as China. In Central Asia, several Tatar tribes had converted to Nestorian Christianity and Nestorian communities could be found in eastern Siberia and were well represented at the Mongol court. So, somewhere in the East, there really was a powerful ruler whose army included many Christians.

This far-flung Christian community of the "Church of the East" suffered terribly during the fourteenth-century conquests of the Turkic ruler Timur, or Tamerlane (died 1405), whose extreme violence (slaughtering vast numbers of civilians) impacted on many communities from India and Russia to the Mediterranean. But that is another – and tragic – story. Prior to that catastrophe, the "Church of the East" stretched across a geographical area much larger than the rest of Christendom.

While medieval western Christendom could be an intolerant place, the general attitude towards this army from "the East" was surprisingly free from the condescending racial baggage that would characterise so much of European attitudes towards non-Europeans from the sixteenth century onwards.

The decision to name the expected ruler "John" may have been due to a confusion in translation of the Karakitai title "Gur-khan", via the Syriac "Yuhanan". The title "prester" (presbyter) was probably derived from "John the Presbyter", referred to in early church writings (after the New Testament) as a possible alternative name for the Apostle John (the sources are not consistent over this identification).

Prester John's remarkable lives

Prester John may not have ridden to the rescue of the crusader states (the Kingdom of Jerusalem fell to Islamic forces in 1187, and the last crusader stronghold, at Acre, fell in 1291) but Europe did not forget him.

According to the thirteenth-century chronicler, Alberic de Trois-Fontaines, a letter arrived in Europe in 1165 that was written by the fabulous king himself. According to Alberic, the letter was sent to the Greek-speaking Byzantine emperor and, from there, was translated into Latin and appeared at the court of the German Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I, Barbarossa.

It was a fiction. There is no evidence that it ever had a Greek original and it was clearly designed as a piece of political spin, which would support the emperor in his struggle with the pope over who had final authority over the Western Church. Rather helpfully, Prester John intimated that he was both a ruler and a church leader (a presbyter). That suited Frederick Barbarossa very nicely.

In addition, the letter stated that John was the guardian of the shrine of Thomas, the apostle, at Mylapore (now in Chennai), India. This underscored his spiritual as well as royal credentials. It also reminds us that medieval Christians were very aware of the traditions that the gospel had gone far to the east as early as the first century. Given Roman trading posts on the coast of western India, this is more than possible and Thomas' connection with the sub-continent may be rooted in fact.

The letter of 1165 promised that John was still intending to come to Jerusalem to win it for Christianity. Nobody seemed to question what he had been doing for the twenty years since his last alleged attempt in 1145. But he still did not come.

During the thirteenth century, as Mongol armies again moved westward, church leaders once more hoped this was a sign of the arrival of Prester John, or a descendant of the great king. In 1221, the crusader army besieging the city of Damietta, in Egypt, heard the encouraging news that "King David of India" (allegedly the son or grandson of Prester John) was on his way. In fact, this was the westward moving army of Genghis, or Ching-gis, Khan (died 1227) whose empire briefly extended from Mongolia to the Adriatic. He certainly was not Prester John; and was not riding to the rescue of Christendom. The terrible destruction unleashed by the Mongol armies on the communities they invaded was not what embattled Christians had in mind.

What is remarkable is that belief in the prester survived even this. In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries several missionaries and lay explorers searched for John's kingdom in Central Asia and as far as China. Unsurprisingly, they did not discover him.

In the fifteenth century, Portuguese explorers in Ethiopia believed they had at last located the kingdom of John. Here was an independent Christian kingdom (established centuries before the colonial spread of the faith), whose rulers claimed descent from Solomon and the Queen of Sheba (1 Kings 10, 2 Chronicles 9); and were mentioned in the New Testament when Philip baptised "an Ethiopian eunuch, a court official of the Candace, queen of the Ethiopians" (Acts 8:27).

The Portuguese asked the baffled Ethiopians about their ruler John (or maybe it was a succession of rulers named John). Since there had never been an Ethiopian ruler by that name, the Ethiopians did not know what they were talking about! And with that, Prester John exited history.

Martyn Whittock is an evangelical historian and a Licensed Lay Minister in the Church of England. As an historian and author, or co-author, of fifty-four books, his work covers a wide range of historical and theological themes. In addition, as a commentator and columnist, he has written for several print and online news platforms; has been interviewed on radio exploring the interaction of faith and politics; and appeared on Sky News discussing political events in the USA. Recently, he has been interviewed on several news platforms concerning the war in Ukraine. His most recent books include: Trump and the Puritans (2020), The Secret History of Soviet Russia's Police State (2020), Daughters of Eve (2021), Jesus the Unauthorized Biography (2021), The End Times, Again? (2021) and The Story of the Cross (2021). He also has an interest in medieval history, being the author of A Brief History of Life in the Middle Ages (2009).