The 'N-word' and free speech: where do limits lie?

It is hard to imagine that broadcasting a cheerful song like The Sun Has Got His Hat On could lead to the dismissal of a radio DJ.

But such has been the fate of BBC Radio Devon presenter David Lowe. He was sacked after putting on air an 82-year-old rendition of the song which contained a racial slur euphemistically described as "the N-word".

Mr Lowe protested his innocence – maintaining he was completely unaware that this particular version contained the word in question. But despite offering an on-air apology, he was dismissed.

BBC bosses have since retreated somewhat – admitting things "could have been handled better" and offering him his job back. But Lowe has refused, citing stress.

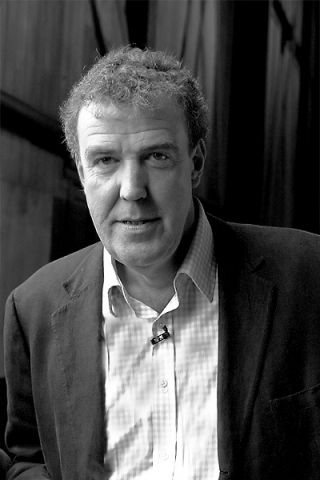

The episode came hot on the heels of an incident in which Top Gear presenter Jeremy Clarkson was recorded using the same word – allegedly inadvertently – while reciting a childhood rhyme. Although the footage was never broadcast, he was given a final warning by the BBC about offensive language.

The very fact that the specific word does not feature in this article indicates that as a Christian I feel uncomfortable using it. Interestingly, by contrast, I see that The Guardian – which many might regard as a bastion of political correctness – had no hesitation about printing it in full, at least online.

So where should the limits lie? Discussions about freedom of speech often begin with a statement attributed to the French writer Voltaire: "I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it." In fact, he never penned these words, although they are generally reckoned to be a fair summary of his views.

Nonetheless, in reality almost everyone – whether Christian or non-Christian – recognises a need for limits on freedom of expression. The question is where that limit lies. In the UK, the 1986 Public Order Act forbids "threatening or abusive words or behaviour". However, Section 5 was modified earlier this year to remove the word "insulting" after a campaign by a diverse coalition (including Rowan Atkinson, Peter Tatchell and Christian groups) which argued it could too easily be interpreted in an over-restrictive way.

For Christians, a central part of our thinking in relation to this issue will be the phrase "speaking the truth in love" (Ephesians 4v15). Indeed, the Apostle Paul lists it as a hallmark of Christian maturity.

Apart from anything else, this must mean that terms of abuse are out. Indeed, Jesus warns bluntly: "If you say, 'you fool', you will be liable to the fire of hell," (Matthew 5v21) – surely enough to bring almost all of us up short. Christians will want to be known for speaking words of love.

At the same time, we will also want to be free to speak the truth. On occasion, this will include criticising practices in society around us – something others may not always like. But at all times we will do so without vitriol.

Over-arching all this will be a sense of mercy. After all, which of us has not slipped up and used rash words on occasion? The Apostle James has a lot to say about the tongue – pointing out that a careless word can function like the spark which starts a forest fire. Yet he also says: "Mercy triumphs over judgement."

In this case, DJ David Lowe seems to have been unaware that the song he was playing contained a racially-offensive word. His offer of an on-air apology should have been accepted. Equally, perhaps he should now consider the BBC's belated offer of reinstatement, if his health permits it – thus showing mercy in his turn too.