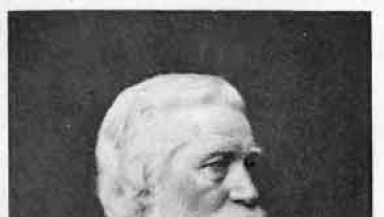

John G Paton was born in 1824 in Scotland, the eldest of eleven children in a poor but devout Christian family. When he was 12, he had come to a personal faith and committed himself to being a missionary. As a young man Paton moved to Glasgow; there he undertook theological and medical studies, was ordained in the Presbyterian Church and worked for 10 years as an evangelist.

He then felt called to what was then the New Hebrides, a long island in the south-west Pacific that is now part of Vanuatu and where heroic mission work had been undertaken for some time.

In 1858 Paton sailed for the South Seas, taking with him his bride Mary. What they found when they landed on the island of Tanna horrified them. Poverty and ill-health, brutal clan battles, cannibalism, infanticide and the sacrifice of widows was practised. Brutality against women was so common that old women were rare. In addition, there was an atmosphere of spiritual fear due to the widespread belief in evil spirits and the practice of witchcraft.

Three months after his landing Paton was struck by a double disaster, losing both his wife Mary and his newborn son to disease. In his grief he found himself alone, struggling with a language that had never been written down and under the constant threat of violence from the islanders. Despite being encouraged to return home, Paton continued to serve for four years under difficult circumstances in which he saw very little fruit.

When in 1862 large-scale tribal warfare broke out, Paton was forced to leave. He then developed a new role as someone who mobilised the church for mission. For four years Paton travelled around Australia and Scotland talking about the needs of mission. He was an inspiring speaker, telling personal stories and speaking with a challenging authority about the need for personnel and financial support for ministry on the islands.

In 1864 Paton married again and with his new wife, Margaret, returned to the New Hebrides, this time to the island of Aniwa. There they were to labour for decades and to have 10 children, four of whom sadly died in infancy. They learnt the local language, wrote it down and translated and printed a New Testament for the islanders.

The Patons were also very much involved in practical help: educating, creating employment and starting medical and social care. The impact of both preaching and practising the gospel was remarkable; within two decades the entire island had become practising Christians.

In 1881 ill-health forced Paton to give up being resident at Aniwa and he became one of the very first worldwide missions speakers, travelling through Europe, Australia and the United States. His influence was helped by his dramatic autobiography and the nickname given him by the influential preacher C.H. Spurgeon as 'the king of the cannibals'. In his addresses, though, Paton was careful not simply to talk about his own adventures and sufferings but also to tell stories of how violent men had, after turning to Christ, been transformed into gentle human beings.

Paton made three worldwide tours and became involved in political action for the New Hebrides, in particular campaigning against slavery which trapped men from the islands. In between his voyages around the world, he returned to the islands and in 1899 was able to give the Aniwans their complete New Testament. With advancing frailty, Paton and his wife retired to Australia, where Margaret died in 1905 and he followed two years later.

Clearly John Paton was a man of outstanding faith but what I find challenging is how that faith was worked out.

Paton's faith gave him courage. He faced extraordinary opposition and in his early years as a missionary had to live with death, loneliness, illness and a constant threat of violence. In particular, after the loss of his first wife and child no one would have blamed him for returning to Britain. Yet he stayed at his post.

Paton's faith gave him confidence. The almost immediate death of his wife and child on Tanna and the seeming failure of his attempts to change a hostile culture for Christ must have seemed strong evidence that he'd been mistaken about God and his calling. Yet Paton persisted through discouragements, believing that God had not only called him but was in control. As Paton was to declare when a precious mission ship was wrecked, 'My blessed Lord Jesus makes no mistakes!'

Finally, Paton's faith was demonstrated in commitment. First, he was a man committed to the gospel. It would have been both easy and understandable for Paton to compromise in his preaching by accepting some of the tribal practices or superstitions. Yet he remained loyal to the historic gospel. He was also committed to his people. Despite living at a time in which many educated individuals considered the peoples of the South Pacific and Australia as subhuman savages incapable of civilisation and destined for extinction or slavery, Paton cared for and valued the islanders.

Believing that social reform went hand in hand with the gospel, he and his wife taught the islanders reading and crafts, built orphanages, had schools erected and dispensed medicine. They battled, too, against those outsiders who sought to exploit the islanders by selling weapons and alcohol.

Although our world is changed from that in which Paton lived, God has not changed. Paton wrote, 'God gave his best, his Son, to me; and I give back my best, my all, to him.'

May we also give back our best, our all to God today.

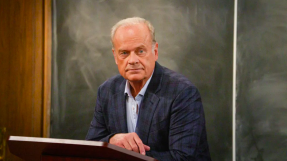

Canon J.John is the Director of Philo Trust. Visit his website at www.canonjjohn.com or follow him on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter.