Towards the end of the Second World War, when there was some hope that a new world order would make the world a better place, the Bretton Woods Conference created the World Bank. The idea was that it would lend money to developing countries for things like roads and reservoirs.

Since then, it's got bigger and more powerful. It's done quite a lot of good when it's got things right, and quite a lot of harm when it hasn't. The massive rise in Third World debt can be laid largely at its door, and the 'structural adjustment policies' it imposed in the 1980s on countries that needed bailouts led to increased poverty, hardship and ill-health for millions.

Now the UN Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights has launched a swingeing attack on the World Bank.

In a remarkably frank report, Philip Alston, a distinguished law professor with wide experience in the field, has accused it of being a "human rights-free zone" which "treats human rights more like an infectious disease than universal values and obligations".

Alston says that the "anachronistic and inconsistent interpretation" of the "political prohibition" in the Bank's constitution is the biggest problem: it believes it isn't allowed to take human rights into consideration when it's thinking about lending money to developing countries, which is what it's there for.

However, Alston goes further: he says the World Bank's real reason to avoid dealing with human rights is political. It's quite possible to put pressure on countries with poor records by refusing to lend them the millions they need. But: "Countries that borrow money from the Bank, or member states that are critical of human rights, don't want the World Bank to turn into a 'human rights cop' that meddles in their internal affairs."

He instances the case of Uganda, which had a $90 million health project loan withheld last year because of concerns about its anti-gay legislation. Alston concludes: "While it was clearly not intended as such, the most significant impact of the decision was probably to convince an even larger number of countries that the Bank should indeed be kept away from human rights issues for fear that it would start to apply sanctions more broadly and in an equally unpredictable and ad hoc manner."

In other words, if you're going to use the leverage of millions of dollars to put pressure on unpleasant governments, you do it consistently.

Now, it has to be said that the World Bank itself has rejected Alston's analysis, with a spokesman saying: "Human rights principles are essential for sustainable development and are consistently applied in our work to end poverty and boost shared prosperity."

Alston has dismissed that, saying in an interview: "The thing that frustrates me most is that a report like mine comes out and what you get are a few dismissive comments attributed to the spokesperson or whoever, but no engagement with the issues.

"Where's it wrong? In what ways are the facts that I describe inaccurate? Where are human rights brought into any of their programming? But they haven't engaged in that debate and I think that's a real problem."

So, where is that analysis wrong? There are some very clever economists working for the World Bank, as Alston admits. At the moment, it will lend to any country that meets its criteria for the loan. But these criteria don't include human rights. So a country might get its roads and reservoirs while continuing to imprison and torture its people, discriminate against poor people, women, gay people and disabled people, and persecute religious minorities. He cites projects in Ethiopia and Uzbekistan and links to an ICIJ report which gives copious examples of World Bank human rights failures.

Alston concludes his report with 16 recommendations. He calls for a thorough review of the Bank's approach to human rights. He says it should be "nuanced" about sanctions (sanctioning every country that violated human rights would leave it with very few clients) but that it should have a "due diligence" policy when it comes to human rights.

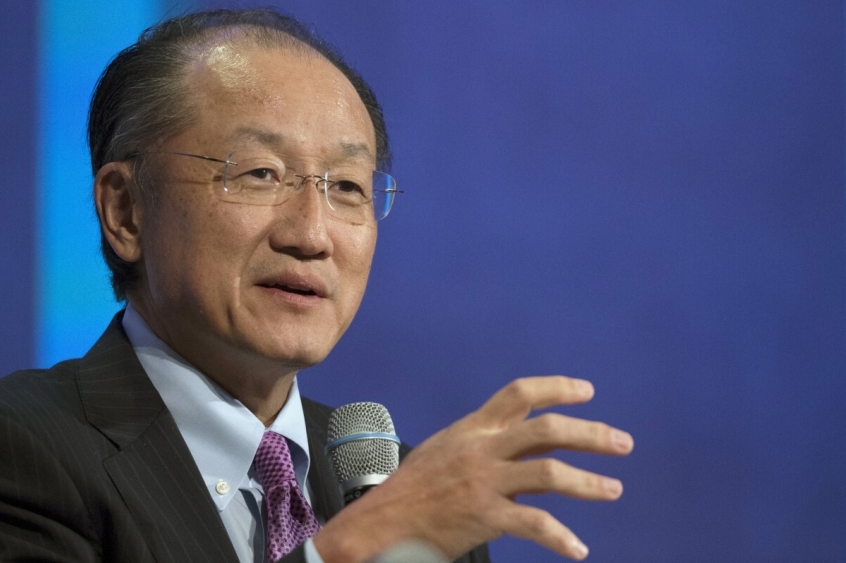

"It is striking how little thought has been given to what a World Bank human rights policy might look like in practice. It is now time for World Bank President Jim Yong Kim to take the initiative," he says.

This is a clarion call that every Christian campaigning organisation with a concern for human rights should hear. What Alston is demanding is a culture change in an organisation which has billions of dollars to spend on projects that affect millions of lives.

It's not too much to ask.

Follow @RevMarkWoods on Twitter.