Tony Blair is a brilliant communicator. He was and is a political genius. I am in admiration of him on so many levels. He managed to do what many of us only dream of in not only leading a movement, but actually putting some its values into political practice.

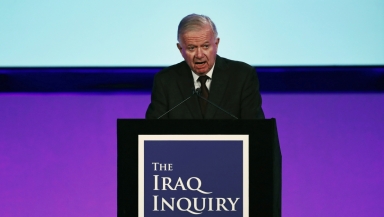

But we all have our blind spots. Hearing him today say the world is a better place because we invaded Iraq makes me sad and mad. Let's gloss over the fact that that assertion is probably nonsense bearing in mind the mammoth death toll, the destabilisation of the region (leading to ISIS amongst other things), Saddam's limited capability and the current-paralysis of Western powers in taking on actual threats. Note: this did not stop his statement being the unchallenged top headline on the BBC website today. My main point is this: please, as you listen to his silky tones, bear in mind that we are being subject to an intense PR exercise. Why does he need a report to bring contrition, bearing in mind he was actually there? Why was there no apology (NB - not for the war) before it was needed for PR purposes? And it is naïve to suggest the content of the report caused a Damascene moment, as reading 2.6 million words in an hour is probably beyond him. It is simply reputation damage limitation par excellence. It is the continuation of a failed, faulty narrative, which is sadly still persuasive to some.

I am glad that the damning realities in the Chilcot report have been exposed, but surely technical discussions about for example whether all peaceful means were exhausted before war tacitly accept the Blair-Bush narrative that taking on Saddam was a vital, immediate, priority.

The bigger question is not whether this situation/war was logistically prosecuted well (which it wasn't), but why the question of Iraq became front and centre at all.

STEALING THE NARRATIVE

Sadly I and many others believe the Iraq war was an opportunistic post 9/11 adventure, exploiting the sympathy, hurt and anger of some very wonderful people. And before you write me off as a peacenik pacifist, please know that I have been in favour of a number of other military interventions in our time. I believe the UK and US at times sadly do have to be the world's police force, if nobody else will, as a last resort.

So the focus should not just be on technical questions of whether the "intelligence" was presented correctly or interrogated well. The problem was that a narrative had to be created to justify a war and therefore the "intelligence" had to be selectively massaged to fit that narrative - that same narrative from which Tony Blair is still speaking today. It wasn't the fault of the "intelligence", or the brave people who tried to accrue it. Blaming it is like blaming the characters of a Mills and Boon novel for the terrible plotline.

Here lies the challenge. Narratives are important. Blair and his team were brilliant at producing them. This is not necessarily a bad thing. I believe many of their narratives bore good fruit in the UK and further afield. We all have narratives. They are the subliminal backbone to how we live our lives whether they sound more like "I have a purpose in life", or "I tend to fail at most things". But we need to pray for high levels of discernment when encountering narratives created by those who have vested interests in how it all plays out, be they advertisers, journalists or pastors. The real battle in our public square is not over which logistical solutions to certain problems are correct. The real battle is for which issues we regard as the biggest problems. While we are distracted discussing the differing solutions to a problem, we haven't stopped to wonder why we think it's the most important problem we face. It may well not be. In 2003 it was Saddam, and in 2016 it was immigration/the EU. The question is - who do we allow to control our imaginations? As Christians especially, we tend to pride ourselves on being very good at knowing God's opinions, but perhaps we aren't so good at gauging his priorities.

Perhaps the main lesson from the Chilcot report (and in fact from Brexit) is to not let the expert story-teller become the sole author of the narrative in which we sit. In this media-led world, the most skilled and entertaining communicators often prevail, especially when their narratives speak to some of our primal emotions like fear. Narratives are part of life but they need to be held accountable to those awkward things called facts. The problem is that is not always easy. It might just be that if we could watch a few less episodes from that box-set, and scroll through Facebook that little bit less we could save some precious minutes for getting at least a little closer to the truth. Perhaps to truly play our part as citizens, we need to not just read the headlines, but think about who put them there and why (including mine!).

Andy Flannagan is director of Christians on the Left and one of the directors of Christians in Politics. Follow him on Twitter @andyflannagan