Jamie Saint's life has been shaped by tragedy and radical transformation. His famous missionary grandfather was murdered by the tribe he was trying to reach out to in 1956. Through years of hard work, the tribe and family have reconciled, and their story has inspired Jamie's missionary work across the world today.

Nate Saint joined the Mission Aviation Fellowship (MAF) in the late 1940s, where he piloted small planes serving missionaries in the Amazon rainforest of Ecuador, South America. In 1955 Saint located an Indian tribe he had been searching for: the Waodani people.

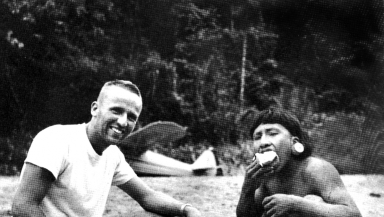

Nate, with the help of four other missionaries including Jim Elliot, initiated contact with the tribe through 13 weeks of gift-giving via 'bucket drops' from his aircraft. The gift-giving was reciprocated by the tribe and so the missionaries decided to make personal contact. There was one successful day of drinking lemonade with tribe members on the beach, but two days later, the missionaries arrived on the beach and were speared to death by the Waodani tribe.

The story of this group – known as Operation Auca – is famous among missionary chronicles. It was a brutal tragedy that saw the missionaries become modern martyrs. But this tragedy was also the beginning of a story of hope.

When I discuss his grandfather's story with Jamie Saint, he offers a startling analysis: 'God did not allow those killings to take place. He actually orchestrated them.'

Saint points to complex tribal politics, only understood years after the fact, that led to the murder of his grandfather. The missionaries unwittingly became involved in a bloody family vendetta that had been taking place at the time of their arrival. Such killings were not unusual in the Waodani tribe, where there was a 60 per cent homicide rate.

However, Saint highlights the unique, precise circumstances of the killings that have led him to conclude that God directly orchestrated the events.

As he explains: 'Without those killings, the next chapter of the story wouldn't have been written.

'Through a series of events, the warrior who speared my grandfather, ended up adopting my Dad.'

The story of adoption and family reconciliation was possible because Jim Elliot's wife Elizabeth and Nate Saint's sister Rachel returned to the tribe. Through years of hard work and communication they brought many of them to Christ. The missionaries developed a written language for the Waodani and a translation of the New Testament.

Soon the Waodani invited the westerners to stay with them and teach them useful skills for meeting the needs of the people.

'You teaching us, together will teach everyone,' they said.

This sharing of knowledge, so that it could be passed on again and again, was the beginning of the Indigenous People's Technology and Education Centre (I-TEC) founded by Jamie's father Steve, with which Jamie now works today.

Jamie says: 'We train Christ followers around the world on how to meet their own people's physical needs, as a door for the gospel.'

I-TEC travel around the world teaching skills of film, storytelling, mechanics, medicine, dentistry. These skills give indigenous people the capacity to meet people's 'felt needs' which calms hostility and gives them credibility for the gospel message they have to share. Jamie says that through I-TEC's ministry, hundreds of thousands, possibly even millions have been affected.

'We have been given this vision by the tribe, and believe this is a biblically correct, culturally sensitive approach to mission,' he says.

Saint sees I-TECs work as part of an emerging approach to mission across the world: 'There's a major push to focus on training and equipping, to empower people rather than going and doing. Not creating dependency, empowering the indigenous Church to be self-sustaining, self-propagating and self-governing.'

This helps keep the focus on serving the people in need, not simply the 'experiences' of those who make the trips. He says: 'When the focus is on what you're gonna get rather than what you're gonna give, then mission goes backwards.'

Does Jamie struggle with the weight of his family's legacy? He refers to a 'big shadow' hanging over him from his father and grandfather.

'I'm referred to as the grandson of Nate Saint or the son of Steve Saint. But God never told me to be Nate Saint or Steve Saint and I can't be those guys...what God wants from me is to write my story in the way that he wants to write it, and use me in the way that he's gifted me.'

The interest in 'God's story' is one that now guide's Jamie's life.

'God has a story to write with each of our lives, while he doesn't promise that every chapters going to be easy, he promises to make sense of even the difficult chapters.

'Years ago, I said, Lord, you write my story...just show me enough so that I can be obedient.'

He says the story of his grandfather has now 'come full circle', as I-TEC still regularly partners with MAF in its work. The relationship with the Waodani tribe – who Saint describes as 'family' – continues, with several visits a year. There are very few killings now, he says, and the Waodani 'take care of us'.

The Waodani people, in contrast to white developed-world westerners, Saint says, have a unique, profound understanding of 'relationship'.

He says: 'In the developed world in the west, we're so scheduled and busy with life. In the jungle if they have food and shelter, that's all there is to life. They spend a lot of time just being together, telling stories – its relational.'

Saint holds no grudges for the killings that took place in 1956.

'They didn't know any better. This is not a story that my grandpa wrote, it's a story that God wrote. If I was to harbour resentment, I'd really be harbouring resentment to the story that God wrote. I've found that's not a good idea.'

You can follow @JosephHartropp on Twitter