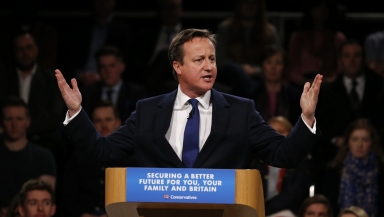

Campaigning in Britain's closest national election in decades will start on Monday after Queen Elizabeth dissolves parliament at Prime Minister David Cameron's behest, teeing up an unusually fraught battle to govern the $2.8 trillion (1.9 trillion pound) economy.

In a ritual steeped in tradition, Cameron will be driven to Buckingham Palace to ask the monarch's approval to dissolve parliament ahead of a May 7 ballot, a formality marking the symbolic end of five years of coalition government between Cameron's Conservatives and the centre-left Liberal Democrats.

Hours later, Cameron, who says he passionately wants another term in office "to finish the job", is expected to lead an election rally in rural England, while the opposition Labour Party is due to present its business policies, warning Cameron's Europe stance poses a "clear and present" danger.

Although the government formally continues until a new one is formed, convention dictates it take no more major policy decisions, while the 650 members of the lower house of parliament revert to being ordinary members of the public.

Britain excels at such set-piece events. But the consequences of the election - in which polls predict nobody will win an outright majority - could be more disorderly.

Britain's continued membership of the European Union hangs on the outcome, as does the future of the increasingly frayed balance of power between the United Kingdom and its most assertive constituent part: Scotland.

In a sign of the uncertain times reflecting the fragmentation of the political landscape, the leaders of the two main parties - the Conservatives and Labour - will on Thursday be joined by the leaders of five other parties for a seven-way TV debate.

The issues on the slate: how to tackle the budget deficit, the future of the country's treasured but troubled National Health Service (NHS), and immigration.

Both the Conservatives and Labour say they want to better manage immigration flows and pump more money into the NHS. The main difference between them is on the deficit with the Conservatives promising to cut it faster with deeper spending cuts and Labour saying it would do it more steadily and fairly.

EU EXIT?

Two polls released on the eve of campaigning underscored the election's volatility. One gave Labour a four point lead, the other gave the Conservatives exactly the same lead.

However, most polls put the two neck-and-neck. None give either enough support to govern alone, meaning that the winner may need to try to rule as a minority government relying on others for backing on an issue-by-issue basis, or go into a formal coalition government with another party.

The contest is freighted with irony. Even though the economy has bounced back from its deepest downturn since World war Two to become one of the fastest-growing in the industrialised world, many Britons say they haven't felt the benefit or that they feel dissatisfied for other reasons.

If Cameron is re-elected, he has promised to deliver an EU membership referendum by the end of 2017, raising the spectre of Britain leaving the world's largest trading bloc, something the United States had made clear it doesn't want.

If Britain voted to leave the EU, Scottish nationalists have signalled they'd push for another independence referendum, even though they lost one as recently as last year.

Labour opposes an EU membership referendum.

Buffeted by high levels of immigration from eastern Europe after 10 mostly former communist states joined the EU, many voters blame the bloc at a time of belt-tightening because of fiscal austerity for pressure on wages and school and hospital places.

Cameron promised to reduce annual net migration to the "tens of thousands." Instead, it's running at around 300,000.

That, for now, makes the outcome of any EU referendum too close to call even though many of the country's big companies want more immigration and for Britain to stay in the EU.

The issue has helped fuel the rise of the anti-EU UK Independence Party or UKIP, a party often compared to the U.S. Tea Party. It wants sharply lower immigration and a swift British exit from the EU, a scenario known as "Brexit."

Britain's winner-takes-all first-past-the-post electoral system means the odds are stacked against UKIP and that it's unlikely to win more than half a dozen seats.

But it has become sufficiently popular, regularly getting double digit support in the polls, to emerge as a potential disruptor that risks splitting the right-wing vote in particular, making it harder for Cameron to win in individual constituencies.

SCOTLAND

Another major disruptor is Scotland.

Nationalists may have lost an independence referendum there last year, but they have bounced back with unexpected vigour. Polls show they could enjoy an almost clean sweep, dealing a potentially knock-out blow to Labour which has traditionally drawn around one fifth of its lawmakers from Scotland.

Ironically, the nationalists, who could emerge as Britain's third biggest party, say they'd only do a post-election deal with Labour, the party they're trying to politically annihilate. Labour leader Ed Miliband has unsurprisingly ruled out entering a coalition with a party that may be responsible for depriving him of an outright win.

But he hasn't yet ruled out doing an informal deal with them, even though their ultimate goal remains the break-up of the United Kingdom.

Publicly, both the Conservatives and Labour say such speculation is pointless as they'll prove the polls wrong and win an outright majority.

Privately, they're less confident.

"It's tough to call, but I think the Conservatives will just about emerge as the largest party," a senior Labour lawmaker, speaking on condition of anonymity, told Reuters.

"But they won't win an outright majority and their government might not last, meaning that before long we might be faced with a second election."