What a 19th-century moral failure tells us about the future of missions

The Bristol Baptist College building in the mid-80s, when I trained for ministry there, had a rather remarkable feature. Walking along the top corridor was a walk through history: each new intake was ritually photographed and duly hung in order, and 50 paces would take you from grimly bearded Victorian heroes to – well, us, who took life rather less seriously. We hung out by the billiard room.

Among those black-and-white pioneers was George Grenfell (1849-1906), who became a missionary to the Congo with the Baptist Missionary Society (now BMS World Mission). An indomitable explorer and evangelist, his story ought to be known by every Baptist. Tireless and fearless, he was the epitome of the heroic age of missions – and yes, he had a splendid beard.

Grenfell has always been a hero of mine – partly because of his exploits on the mission field, but partly for a very different reason.

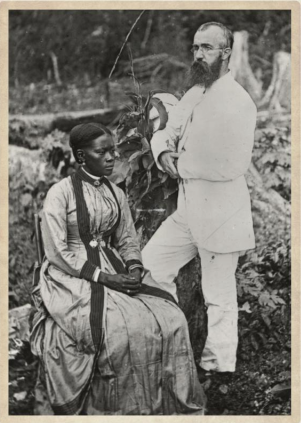

He was married, first, to Mary ('Polly') Hawkes, who died in 1877 at Victoria in the Cameroons after giving birth prematurely. Surviving pictures of Grenfell's family, however, show him with another woman, who is black.

She is Rose Edgerley, a Jamaican, who was his housekeeper and a member of the church in Victoria. After Polly died, Grenfell, overcome with loneliness, began what we would now call a 'relationship' with her and she became pregnant. The affair became known; Grenfell resigned from the Society and worked for a commercial concern. He and Rose married, and had a daughter.

Two years later, Grenfell was re-engaged by BMS as superintendent of the Congo mission station at Musuku. His family went with him. It was, by all accounts, a very happy marriage. Patience, his eldest daughter, was educated in England and Brussels and herself became a teacher in the Congo, where she died of haematuric fever at Bolobo in 1899. It was common enough: the missionary death-rate was appalling. Those at the other end of our corridor from Grenfell would have regarded it as a wholly unacceptable risk.

But what's so heroic about that, and what does the story have to say about the future of missions?

I don't, in fact, want to excuse him too much. He was in a position of power, and he abused it. That is never acceptable. He was right to resign, and it was right that his resignation was accepted.

But he was also right to marry Rose, at a time when white men were using black women for sex on an industrial scale without the remotest sense that they were responsible for the consequences. Whatever the initial irregularity, he and Rose seem to have cared deeply for each other. Would they have been 'allowed' to marry, from the BMS point of view, if she had not been pregnant and he was still a serving missionary? It seems unlikely; this was 1878, close to peak Empire, and miscegenation was generally seen as letting the white, civilised side down. In wider colonial society, white men could take black mistresses, but if they married them they lost caste. Grenfell did it anyway, because he was a fundamentally decent man.

And what about the future of missions? It doesn't have much to say to us about race; that hang-up has largely vanished among sensible people. On the other hand, in the age of #MeToo and hyper-awareness of sexual power relationships, it seems very contemporary.

To me, though, it speaks of something else entirely. Modern mission workers have more in common with those High Victorian spiritual empire-builders than they might think.

There's a model of mission that involves agencies like BMS exporting the best and brightest the church has to offer. They go to foreign parts to solve problems and meet needs, and do things that receiving churches can't. They are able and educated, driven and dedicated. They want to change the world, and they are prepared to labour for the cause in obscurity, sometimes in danger. They are called to serve, and they will go where they're called.

They are, in their way, heroes of the faith, though they would all deny it. And of course that's entirely appropriate – if mission agencies are to continue to have value, they have to identify and send those who are best equipped for the role to which they're called.

But Grenfell shows us another side of heroism. He was a flawed, vulnerable and sinful human being, very far from a spiritual superman. He epitomised not just the strengths of the empire-builder, but its weaknesses. Whatever the romantic element of his relationship with Rose might have been, it can't be divorced from the fact that he was a white European in a land of black people at a time when that made him automatically one of the masters. Rather than maintain that privileged distance, though, he entered into an equal marriage partnership with her.

And Grenfell's situation, it seems to me, has something quite profound to say about mission workers today. Though they have certain strengths, they cannot operate from a position of strength. They go to people from different cultures, who speak different languages, to share their lives with them rather than just to do a job. The relationship is one of absolute equality between the receivers and the sent, tempered, on the side of the sent – as Grenfell's was tempered – by an acknowledgment of past injustices. They go, not in power, but in weakness.

The old Bristol College building was sold years ago, and the pictures are in albums somewhere. That's just as well, because history is not just linear, a line down the corridor from fading mid-Victorian sepia to straight-to-Instagram digital snap. The past teaches us the future. We have a lot to learn from that picture of George and Rose.

This article first appeared in Mission Catalyst and is reproduced with permission.