What Eugene Peterson taught me about preaching

One of the most helpful things anyone ever said to me about preaching was when I was a very young preacher and had preached a very bad sermon. I admitted it to the pastor of the church where I was a student, who was wise enough not to contradict me politely. Instead he said: 'Don't worry. You can't strike oil every time.'

The reason I found that so helpful was that it gave me permission to fail. I wouldn't always succeed in gripping people's attention for 25 minutes, rocking their spiritual world and gloriously converting every unsaved person present. Sometimes I'd try my best and it wouldn't be good enough – and I shouldn't worry, if only because next week I could try again. That's comforted me immensely during the succeeding decades.

But, but. Preachers and leaders of worship have been given the responsibility of mediating an encounter between God and his people. They help shape a lifetime of discipleship. Once in a while, they get a pass when they preach a boring sermon. But a habitually boring preacher ought to be a contradiction in terms.

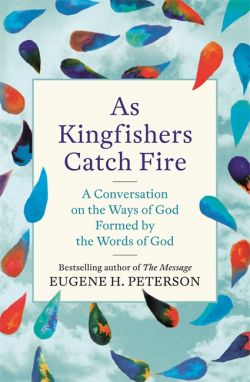

Eugene Peterson, who died this week, was one of his generation's most loved and influential spiritual teachers. Again and again his insight would illuminate a story or passage of Scripture we thought we knew all there was to know about. One of his last books was a collection of sermons, As Kingfishers Catch Fire (the title is from a poem by Gerard Manley Hopkins) preached at his Presbyterian church in Maryland over 29 years. In one of them, on Deuteronomy 11, he recalls his fascination with the terrible romance of the French Revolution when he was a student: 'Names like Marat, Robespierre and Danton had a ringing and righteous sound in my ears... Heroism and villainy were in apocalyptic conflict.' He found a course on it and signed up, all youthful enthusiasm to know more. It didn't work out well. The lecturer 'spoke in a soft, timorous monotone'. As a teacher, she was a disaster: 'She knew everything about the French but nothing about revolution.' 'Everybody sounded the same in her lectures, all presented as neatly labeled specimens, butterflies on a mounting board on which a decade of dust had settled.'

So much for the French Revolution, for Peterson at least. Then, as a young pastor, he was astonished to find his congregation yawning too. One man literally fell asleep. A teenager read comic books. Others passed notes on stock market tips. One woman gave him hope by noting down his sermons in shorthand, but she was planning to leave her husband and practising for the job market.

In his Deuteronomy sermon, he reflects on the transformative effect on the Hebrews of King Josiah's day of finding the long-lost Book of the Law. 'This sermon [that is, Deuteronomy, presented as a sermon by Moses] does what all sermons are intended to do: takes God's words, written and spoken in the past; takes the human experience, ancestral and personal, of the listening congregation; and then reproduces the words and experience as a single event right now, in this present moment. A sermon changes words about God into words from God. It takes what we have heard or read of God and God's way and turns them into a personal proclamation of God's good news. A sermon changes water into wine.'

When it comes to preaching, everyone – preachers and congregations – starts in different places. Preachers are differently gifted, both in natural speaking ability and in their insights into Scripture. And there's no point in trying to preach someone else's sermon, either: what carries the ring of truth from one person sounds forced and false from another. Sermons are not mechanical repetitions of biblical 'truth'; they are the result of a reaction between the mind and heart of the preacher and the raw materials of Scripture and experience.

Congregations are different, too – and we're quite wrong if we imagine that the experience of worship–through-sermon depends entirely on the preacher. It may be that some preachers are objectively 'good' and others objectively 'bad' (though who is to say which is which?). Just as important, though, is the attitude the congregation brings to worship – which can be shaped, over time, by the minister.

A church might have a culture of carelessness, in which the congregation doesn't expect to be changed by what they hear. Sermons might be there to be endured. Their content is stale and predictable, and the congregation is predictably stale. Water is never transformed into wine, and palates become so dull that no one ever notices.

One of the things that transformed Eugene Peterson's own preaching, he tells us, was when he began to treat his congregation with dignity. 'Impatience began to diminish; condescension slowly faded out. I was learning to embrace the congregation just as they were, not how I wanted them to be. They became an integral part of the sermon.'

And it's surely in this deep partnership between preacher and people that the spiritual magic happens. No, preachers don't strike oil every time. But they never need to be boring, if they and their congregations are devoted to not just to the Bible, but to spiritual revolution.

'As Kingfishers Catch Fire' is published by Hodder.