What is the legacy of the Six-Day War, which began 50 years ago today?

The Six Day War, which began 50 years ago today, marked not only an immediate, decisive victory by Israel over its Arab neighbours, but also began the occupation with a hugely successful Israeli land-grab. It has had a major, lasting impact on the conflict between the Jewish state and the Palestinians which remains unresolved to this day.

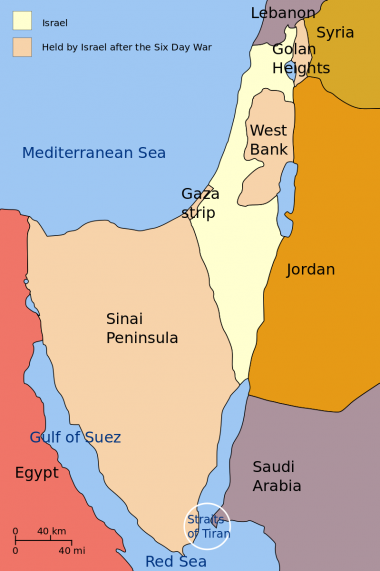

The war, also known as the June War or the 1967 Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and the neighbouring states of Egypt, Jordan, and Syria. Israel's victory included the capture of the Gaza Strip, West Bank, Old City of Jerusalem, Sinai Peninsula and the Golan Heights.

First, the context. Tensions grew in the months preceding the war, with Palestinian guerrilla groups based in Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan stepping up attacks on Israel, leading to heavy Israeli reprisals.

For example, in November 1966 an Israeli strike on the village of Al-Samū in the Jordanian West Bank left 18 dead and 54 wounded, and during an air battle with Syria in April 1967, the Israeli Air Force shot down six Syrian MiG fighter jets.

Meanwhile, the Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser had been strongly criticised for his failure to come to the aid of Syria and Jordan.

In response, he sought to demonstrate total support for Syria, and on May 14, 1967, Nasser mobilised Egyptian forces in the Sinai.

An alliance against Israel was building. On May 30, King Ḥussein of Jordan arrived in Cairo to sign a mutual defense pact with Egypt, placing Jordanian forces under Egyptian command, and shortly after that Iraq joined the alliance.

Then Israel struck. Early on the morning of June 5, the country staged a sudden, pre-emptive air assault that destroyed more than 90 per cent Egypt's air force. A similar assault incapacitated the Syrian air force.

Within three days, the Israelis achieved an overwhelming victory on the ground, too, capturing the Gaza Strip and all of the Sinai Peninsula up to the east bank of the Suez Canal.

An eastern front in the war opened on June 5 when, despite a warning from Israel to King Hussein that Jordan should stay out if it, Jordanian forces began shelling West Jerusalem. On June 7, in a crushing counter-attack, Israeli forces drove Jordanian forces out of East Jerusalem and most of the West Bank.

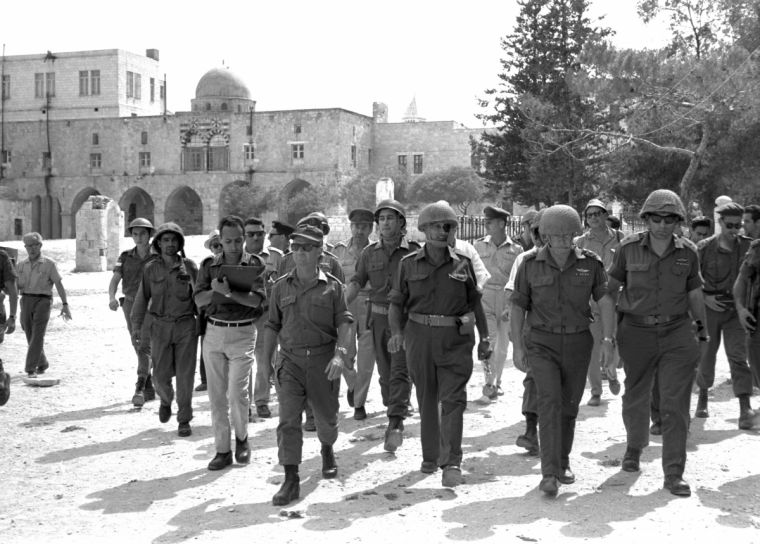

Israel took control of the Old City of Jerusalem, a move that is still celebrated in the country today, and photographs of Israeli troops in the Old City remain iconic images of the war and its result.

On June 7, the UN Security Council called for a ceasefire that was immediately accepted by Israel and Jordan, with Egypt also accepting the following day. However, Syria tried to hold out, continuing to shell villages in northern Israel. On June 9, Israel launched an assault on the Golan Heights, capturing it from Syrian forces after a day of heavy fighting. The following day, June 10, Syria relented and also accepted the ceasefire.

Overall, the Arab countries endured massive and asymmetric losses: Egypt's casualties were more than 11,000; Jordan's 6,000; Syria's 1,000 and 700 for Israel.

The Arab countries were heavily demoralised. Nasser announced his resignation on June 9 but stayed in office by popular demand through public demonstrations.

There was euphoria in Israel, which had asserted itself beyond question across the region. Israel's victory was total. In a matter of days it had swept away the deep fears Israelis had harboured and which most in the country saw as critical to the state's survival.

What, then, is the war's legacy? It remains one of Israel's dominance of the region, to the cost of Palestinians.

Today, around 600,000 Jewish settlers live in 140 settlements in occupied East Jerusalem and the West Bank. The settlements – not supported by all Israelis by any means -- are deemed illegal under international law.

Fifty years on, the Palestinians remain without their own state and effectively imprisoned in a maze of checkpoints closures and military zones, deprived of civil and political rights and governed by martial law.

Indeed, the consensus which has emerged over the decades, of the need for a 'two-state solution', would involve the Palestinians ending the conflict in return for a state on Gaza, the West Bank and East Jerusalem, which makes up only 22 per cent of historic Palestine.

Many believe that only outside pressure, primarily from the US, can lead to the resolution of the conflict.

Donald Trump, who visited the region last month, has said that he believes both sides want peace, despite critics arguing that Israel's right-wing Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, secretly preferring the status quo.

But even if Netanyahu was willing to do a deal, there remains the issue of the leadership of the Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas, who is said in the region to lack authority.

It does appear that now represents what Justin Welby, the Archbishop of Canterbury who also visited the region last month, called a rare 'moment of opportunity' for peace.

But 50 years after the Six-Day War, that peace, alas, remains as elusive as ever.