What makes a real leader? Deuteronomy has the answer

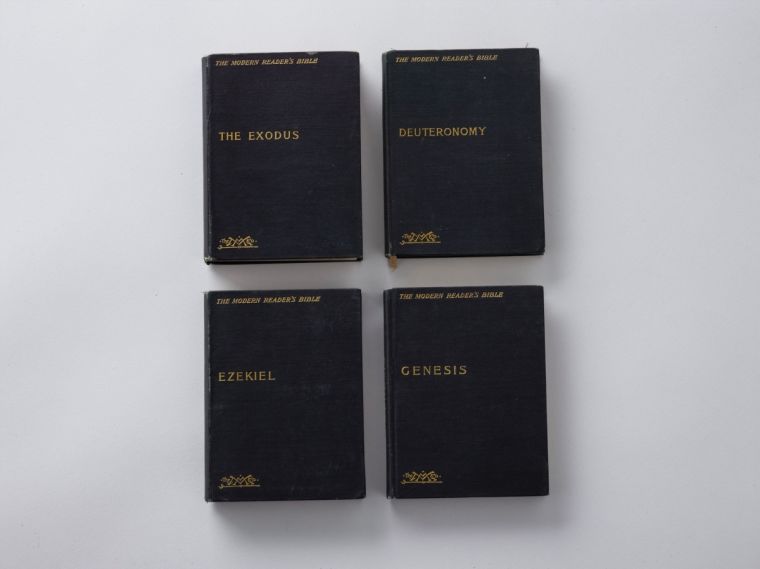

Jewish academic and Hebrew scholar Irene Lancaster reflects on what Deuteronomy has to say about leadership.

Recently, we have been hearing a great deal about leadership. One UK political leader has been ousted and the frantic rush to replace him with more of the same is simply staggering.

The former leader of the Soviet Union has just died, aged 91, and has been heralded as the person who saved the Russian people from certain ignominy, as a traitor to the Communist cause, or even akin to Moses, the reluctant Jewish leader who took the Jewish people out of bondage, but did not himself reach the promised land.

We have also recently witnessed the 50th anniversary of the Munich Massacre of 1972, when Palestinian terrorists murdered Israeli athletes and trainers as they slept in their beds, and Germany failed to save the day.

And finally of course, the 25th anniversary of the death of Princess Diana. This took place on the same day as my daughter, aged 22, witnessed a bomber blowing up a Jerusalem bus coming towards her, people literally cut in half, and body parts strewn all over the road. She rang to say she was 'OK' and that is why I remember every last day of August.

It might therefore be interesting to investigate how the Hebrew Bible deals with the question of leadership. In fact, our current Sedra of the week, Shoftim (Judges) from the book of Deuteronomy 16:18–21:9) - Devarim – meaning 'words' is the only place in the Hebrew Bible which discusses the question of monarchs.

Otherwise, the Hebrew Bible is far more interested in the treatment of the weak and dispossessed, the stranger, the widow and the orphan, and how 'you', the ordinary individual, will treat these disadvantaged members of our society.

No other book in the Ancient Near East deals with widows, orphans and 'strangers' in the way that the Hebrew Bible does, targeting the behaviour of the ordinary person – me and you. In other words, leadership, although necessary, is definitely not sufficient in Jewish law and Jewish lore.

It is highly curious that the Hebrew Bible does not tell the people to obey their king. What is more, the monarch's power is drastically curtailed. David fails, because he increases wives (thus, cementing treaties with other nations). Solomon fails because, although he builds the First Temple, he accrues wives (international political power), horses (weapons of war) and amasses riches, increasing taxes on his subjects in order to finance his vast power. Remind you of anyone?

No, we Jews are supposed to listen to our judges and prophets, not to the 'brother' whom we appoint to be king. So, in the eyes of G-d, the king, who is at best a necessary evil, a sop to human nature, is to be regarded at source as on a par with everyone else. Judaism is a most democratic system of religion, politics and government.

We have therefore established that the Hebrew Bible is far from advocating monarchy as the ideal form of government. But if, after the warnings given against the institution of monarchy, the Jewish people nevertheless yearn to be like other peoples, so be it. Let them have their royal leader, as long as his role is not confused with the priestly role, and as long as the priestly role is differentiated from the role of the judges (keeper of the law), and as long as the prophets have their own role as transmitter of the Divine word. And no, the prophet is not like the Senior Minister. And neither is the Jewish monarch is to become 'world king.'

Because Judaism has a very simple teaching. People who are willing to give up everything in the end will gain everything. Let us take the greatest example of this idea. No one would disagree that the prophet Moses, who brought us out of Egypt, is the greatest Jewish person who has ever lived. But even Moses was far from perfect. First of all, he didn't think he was a very good communicator, and therefore asked his brother Aaron to act as his mouth-piece. But the trouble with PR people is that they usually want to curry favour, and unfortunately, that is what Aaron, for all his outstanding qualities, did with regard with the Gold Calf incident (Exodus 32).

And Moses also seems to have lost his temper when he struck the rock to obtain water for the clamoring people. G-d had told him simply to 'speak' to the rock (Numbers 20). But isn't it often the case with people who find it hard to communicate that they often lash out! What an irony that Moses had no choice but to resort to striking the rock. And that is why, at the end of his life, Moses is forbidden entry to the Promised Land.

Not only is Moses unable to enter the Promised Land, but it is not known where he is buried. Moses, the greatest Jew who ever lived, simply is no more. Maybe, that was for the best. After all, had we known where the greatest Jew of all time had died, then his grave would have become a shrine, and therefore encouraged pilgrims, and that might have led from reverence to worship. And Moses, who strictly forbade idol worship, would have become an idol himself. So maybe, it was all for the best.

And what then does Moses tell the Children of Israel in his final speech, as he is about to depart from this world. This is the subject of the Torah reading for Shabbat, known as 'Shoftim' (Judges) (Deuteronomy 16:18-21:9), as mentioned above.

On entering the Promised Land of Israel, the children of Israel should first set up law courts and appoint judges. As the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg rightly emphasized: 'Justice justice shall you pursue' (Deuteronomy 16:20). Not kings, but judges, are to be the supreme arbiter of Jewish life.

Second, the children of Israel should not set up temples, or even shrines, all over the place and worship false gods. Why? Because, setting up temples detracts from behaving justly. Temples involve labour, the importing of materials from abroad, and detract from the emphasis on the everyday positive behaviour, the care for others, which are the hallmark of the just and merciful society.

In the only place in the Hebrew Bible where the role of the monarch is described, what does Moses tell us about the role of the future kings of Israel? In Deuteronomy 17:14-20, Moses describes first what the monarch must not do, and then what he should do.

And it goes as follows: 'When you enter the Land that the Lord your G-d gives you, and take possession of it, and settle it, [only then] will you say 'I will place over myself a king.''

So, first arrange the infrastructure, the way things work in society, and only then will G-d Himself choose a person, 'a brother' and not a 'foreign person'. In other words, the person who would be king should have first worked with everyone else to build up the infrastructure, and only then will G-d choose him to rule. Bottom up, not top down, and certainly not a priest king. Separation of powers is essential.

Secondly, apart from being one of the people, the new monarch should not amass horses (weapons of war), as these will lead back to the Egypt mentality which the children of Israel have now discarded. Neither should he have too many wives (with obligations to the nations from which they come). And he shouldn't store up great wealth, as wealth distracts from the true job at hand.

So what should the Jewish monarch, appointed by G-d, actually do?

'He shall write for himself two copies of this Torah in a book, in the presence of the Kohanim, the Levites.' In other words, one copy of these words of Torah from the mouth of Moses will be kept safely in the store house, and the other must be with the monarch at all times. These scrolls are to constantly remind the monarch that he is the servant of the Torah. Instead of accruing wealth in his store-house, he places the priceless copy of the Torah there in its place.

'It shall be with him, and he shall read from it all the days of his life, so that he will learn to fear the Lord, his G-d, to observe all the words of this Torah and these decrees, so that he can carry them out, and so that his heart does not become haughty over his brothers, and not deviate from the commandment right or left, so that he will prolong years over his kingdom, he and his sons amid Israel.'

Throughout history, we have experienced monarchy and other kinds of supreme leadership which go against the definition of monarch in the Hebrew Bible. Most of these monarchies and other types of supreme leadership are imbued with an aura encouraging worship, if not hysteria.

Whether it is regal leadership as exemplified by emperors, kings, queens, princes, princesses, dukes, duchesses, or political leadership as exemplified by presidents, prime ministers and the like, most have not lived up to the values of the Hebrew Bible. Likewise, religious leadership also often falls short, paying lip-service to humility, but exuding pride and arrogance.

The lesson of the Hebrew Bible is one of equality before G-d, with people of expertise being encouraged to work separately in the spheres of law, prophecy, priesthood and, last of all, sovereignty.

But, to repeat, it is to prophets and judges to whom we should have recourse: to those who really know what G-d requires of us, and to those who understand the law, and know how to keep our world from falling apart. Kings are very much a last resort in the Jewish psyche, while judges and prophets are extolled.