What now for the West, after Afghanistan?

We live in a world that is interconnected across time and space. Sitting at my desk, I am looking at two very different objects which remind me of this. The first is a British army cap badge from my father's old regiment (the Somerset Light Infantry). It carries the battle honour: 'JELLALABAD.'

Before the last few days, most people here had never heard of Jellalabad, in Afghanistan. But it is interwoven into the history of this West Country county regiment (now long amalgamated with other regiments, as part of army restructuring).

As the '13th Regiment (Light Infantry)', it was besieged at Jellalabad in 1841-42, during the 'First Anglo-Afghan War'. It broke out of the siege (hence this 'battle honour' on its badge), although the war itself failed to achieve British objectives. The war was famous for the disastrous 'Retreat from Kabul' in 1842, when the British and East India Company forces attempted to retreat from Kabul to Jellalabad. Out of more than 16,000 people in the column, only one European (Assistant Surgeon William Brydon) and a small number of Indian soldiers reached Jellalabad.

The war was part of the struggle for supremacy in the region, between Britain and Russia, known as 'The Great Game', but for those on the ground – civilians and soldiers – it was anything but a 'game.'

There is a second object on my desk. It is a crisp Afghan bank note. Printed on it are the words: 'PRAY FOR US.' Many years ago it was given to me by a friend at church who was encouraging us to pray for the country. For a while I did...but then other things happened and I forgot.

Then a friend was posted to Bagram Airfield, north of Kabul, with the RAF. It was at a time when many members of the UK armed forces were serving and dying in Afghanistan. That prompted me to pray again. Eventually, my friend returned safely to the UK and Afghanistan once more drifted off my radar. Last week it was on everyone's radar again, as we witnessed the rapid advance of the Taliban and the tragic and chaotic scenes at Kabul Airport, that are ongoing.

Over the next few weeks there will be much discussion – and recrimination – centred on the questions of: 'Why has this happened?' and 'Who is to blame?' This discussion is already well under way. This will be accompanied by addressing how to respond to the thousands who are desperate to leave the country. But another, equally pressing, question is: 'What now for the West, after what has occurred in Afghanistan?'

This is also a crisis for the West

What has occurred is, first and foremost, a crisis for Afghanistan. It is right and proper that this is centre-stage at present. However, it is also a crisis for the West and its influence in the world.

In China the Global Times, a Communist Party media outlet, asked the rhetorical question: "Is this some kind of omen of Taiwan's future fate?" It went on to conclude that, "The US would have to have a much greater determination than it had for Afghanistan, Syria, and Vietnam if it wants to interfere."

Another Chinese newspaper suggested last week that the Taiwanese government might want to invest in Chinese flags now, ready for when it eventually has to surrender. Xinhua, the state news agency, commented that "The fall of Kabul marks the collapse of the international image and credibility of the US."

China is keen to get access to mineral resources in Afghanistan and sees the country as a potential part of its so-called 'Belt and Road Initiative,' geared to boost China's trade and influence across Asia and around the world. This also ties in with its huge investment in port facilities in Gwadar, in Pakistan.

Despite sharing a mere 47 miles of border with Afghanistan, the Chinese are keen to develop a positive relationship with the Taliban, as long as the Taliban does not provide assistance to China's Uighur Muslims, who are suffering ferocious persecution at the hands of the Chinese communist regime. The signs are that, in an act of pragmatism, the Taliban look likely to cut the Uighurs adrift.

Russia too will be more than happy to see the US humiliated in Afghanistan and no longer a serious player in Central Asia. Like the Chinese, Putin's regime has developed a relationship with parts of the amorphous Taliban movement in regions bordering Russian territory; including (some reports suggest) financial aid. Like the Chinese, the Russians have an eye on the mineral resources of Afghanistan and are keen to develop a working relationship with the new regime. Russia is also keen to put behind it the catastrophic experience it had in Afghanistan in the last years of the Soviet Union.

Pakistan, whose secret service has long channelled assistance to the Taliban, will be happy to see a dependent state developing there and one which will back Pakistan in its bitter relationship with India.

Though the West has lost in this tragedy, there are certainly other states who see their interests enhanced by the collapse of the Western-backed regime in Afghanistan. However, the repercussions go wider yet...

The delusion of the 'Special Relationship'

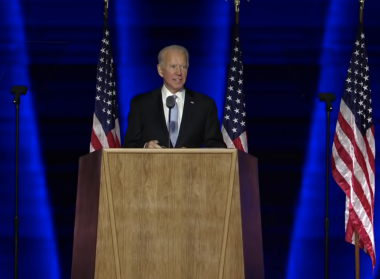

There are close historic and cultural ties between the UK and the USA but, make no mistake, US interests clearly come first for all incumbents in the White House. The presidency of Joe Biden may have promised that 'America is back' but there are clear limits to how far the US is prepared to commit itself abroad. Anyone who thinks that the UK can build its future on the basis of a trans-Atlantic relationship is deluding themselves.

This means that the UK has to think very clearly and determinedly about its wider network of friends. It might start with not sacrificing good relationships with its closest neighbours. Otherwise, 'Global Britain' will find the world can be a very cold and unfriendly place.

Whither the Western Alliance? Wither Nato?

Last Wednesday, in the House of Commons, Theresa May posed a very difficult question: "What does it say about us as a country, what does it say about Nato if we are entirely dependent on a unilateral decision taken by the United States?" It was, and is, a good question. Already, politicians from the Baltic States have raised questions regarding the reliability of the US if it comes to conflict with Putin's Russia.

Developing a Nato alliance in which the US is not a leading player is hard to imagine. But it is, perhaps, time to think the unthinkable. And this will have financial costs, as well as make demands on political will. The security of the European continent (of which the UK is a part due to geography and history) may depend on this. We have become overly reliant on the US. It is surely time to shift more of the heavy lifting onto the whole Nato community.

Are Western values still exportable?

If, by 'Western values,' one means human rights (including the rights of women), the rule of law, representative government, a free press and multi-party free elections, then I certainly hope so. These remain values worth extolling, defending and exporting.

In many ways, they arise directly from a Christian heritage and we need to recognise that. The Enlightenment may have sought to distance itself from a past that was dominated by faith, but the simple reality is that it built on the Christian principles which had influenced the development of European culture over a millennium. But we have to become better at communicating these values to others. And better at offering support to those who represent these values in other parts of the world.

At present we see regimes in China and Russia who offer investment and support with no moral or ethical strings attached. If Western values are to mean anything in the competitive world of 'soft power' foreign policy then they cannot be regarded as optional extras. Too often we in the UK – as other Western nations too – set these to one side when we see a trade opportunity on the horizon. If the West is not to become an irrelevance we need to be clear about our values and stand by them.

The tragedy of Afghanistan (as Iraq and Libya) has revealed the apparent inability of the West to impose its values via military intervention geared to regime change. However, this is not the same as making Western values irrelevant. What is needed is a re-imagination of how to export these values.

We need to be prepared to risk economic disadvantage by talking about human rights in negotiations. Instead of cutting our aid budget, we should be seen as an ethical investor in the future of others. We need to engage more actively with international efforts to relieve the human tragedies represented by global asylum seeking and migration. We should focus more on the soft power inherent in things such as the BBC World Service. We should target sanctions at individuals and institutions abroad implicated in human rights abuses – and avoid broad-brush sanctions that hit whole communities.

We should root out the 'dirty money' (linked to oppressive regimes and their supporters) that has been allowed to infiltrate our economic systems. We should speak out on behalf of minorities abroad (many of whom are Christians) who are being persecuted. As Christians, we should give political support here to those who adopt such policies and strategies.

And, in the meantime, I am using that Afghan bank note as a book mark in my Bible-reading notes. This time, I will try harder to remember to pray for Afghanistan.

Martyn Whittock is an evangelical and a Licensed Lay Minister in the Church of England. As an historian and author, or co-author, of fifty-two books, his work covers a wide range of historical and theological themes. In addition, as a commentator and columnist, he has written for a number of print and online news platforms; has been interviewed on radio shows exploring the interaction of faith and politics; and appeared on Sky News discussing political events in the USA. His most recent books include: Trump and the Puritans (2020), The Secret History of Soviet Russia's Police State (2020), Daughters of Eve (2021) and Jesus the Unauthorized Biography (2021).