Who Was Philip Melanchthon? The Protestant Reformer In 5 Quotes

Today marks the birthday of a man who was essential to the Protestant Reformation, though he's not nearly as well known as some other Reformers. His name was Philip Melanchthon.

Melanchthon was a friend of Martin Luther's and was heavily influenced by his theology, though the pair also disagreed on some key issues. Melanchthon was known for his caution and concern for peace, as well as his great intellect. Luther would write of him: 'I had to fight with rabble and devils, for which reason my books are very warlike. I am the rough pioneer who must break the road; but Master Philip comes along softly and gently, sows and waters heartily, since God has richly endowed him with gifts.'

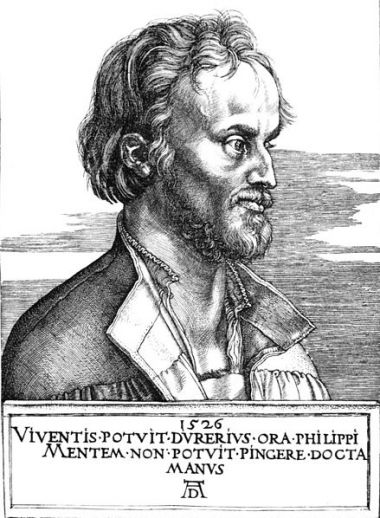

Melanchthon was not a particularly good-looking man – his rather scrawny look in the Lucas Cranach portrait shows why Luther would describe him as a 'shrimp'. Nonetheless, Melanchthon was a great mind, who 500 years after the Reformation still has much wisdom to offer the Church.

On creation

Melanchthon said: 'God willed to become known and to be recognised.' He emphasised God's deep connection with the world as its creator, who desires to be known.

For Melanchthon God is not like the carpenter of a ship who hands his work over to the sailors once it is complete, but rather 'God is present with his creation...sustaining his creation and governing it with His measureless mercy, bestowing good things upon it...' Melanchthon saw God as a benevolent, merciful creator; not distant from his creation but deeply involved with it.

On sin and grace

Melanchthon defined human sin as 'a darkness in the mind...[wherein] the will is without a fear, love or trust in God'. Since the fall of Adam this darkness has been present within humankind. In our turning away we are separated from God. He wrote, 'Original sin is the lack of original righteousness which is required to be present in us.'

In his writing Melanchthon emphasised the difference between 'law' and gospel'. The law, seen in Old Testament teachings in particular, condemns us like a harsh schoolmaster, showing us our original sin and inability to keep the commands we are given. In stark contrast comes the gospel, the free gift of life that comes despite our unworthiness, and therein lies 'the sweetness of the name' of Jesus.

One of his more famous quotes is: 'To know Christ is to know his benefits.' Christ's gospel is the radical alternative to living under 'law'. He takes away the sin of humankind, giving righteousness and eternal life in its place. Some critics felt that Melanchthon undermined God's gift of the law by opposing it to 'gospel', and that focusing on the 'benefits' of Christ reduced the gospel and took away from the idea of knowing God personally.

On predestination

Melanchthon was deeply troubled by the doctrine of predestination put forth by his contemporary John Calvin. Calvin taught that God elects some to eternal salvation and others to eternal damnation. As Calvin wrote: God 'does not indiscriminately adopt all into the hope of salvation but gives to some what he denies to others'.

The idea that some are promised salvation and others damnation is one that Melanchthon felt could only lead to doubt and a troubled mind. Where was free will? How could you know for certain if you were elect or not? Melanchthon dismissed the doctrine as dangerous, distracting speculation. For him the gospel needed to be a free gift, offered to all, and be a promise that could not be doubted.

On the truth

Melanchthon penned the Loci Communes in 1521, the first full elucidation of Lutheran theological beliefs. He cared about the truth. As he said: 'We must seek the truth, love it, defend it, and hand it down uncorrupted to our posterity.'

However, he also supported the idea that certain truths were of secondary importance. He described certain doctrines as adiaphora, which is Greek for 'things indifferent'. Belief in salvation through the cross of Jesus was essential to Christian faith, but issues like whether the Lord's Supper was literally or symbolically the body and blood of Christ, were adiaphora. Critics said this made Melanchthon a compromiser, while others said it made him a positive peacemaker.

On death

Melanchthon led the Lutheran movement after Luther died in 1546. On his deathbed in 1560, Melanchthon encouraged people not to fear death, because in death one would 'be freed from the acrimony and fury of theologians'. Living at the heart of the turmoil of the Reformation, Melanchthon knew the anger of theologians well.

More positively, he also said that people should not fear death because when it comes, 'Thou shalt go to the light, see God, look upon his Son, learn those wonderful mysteries which thou hast not been able to understand in this life.'

You can follow @JosephHartropp on Twitter