I've been uneasy about Ted Cruz for months, ever since I first realised the extraordinary positions he takes – in common with most of the other Republican candidates – on issues like climate change and healthcare. As someone who doesn't have a vote, the latter is arguably none of my business. The former certainly is: America's influence is vital in helping to limit global warming, and I'll take the almost universal scientific consensus any day.

I worry, too, about his personality. Never met him, don't want to, but to me he's clearly a street fighter for whom winning is more important than being right. No compromise, no negotiation, no reflectiveness, no generosity. You know your enemy and you take him out.

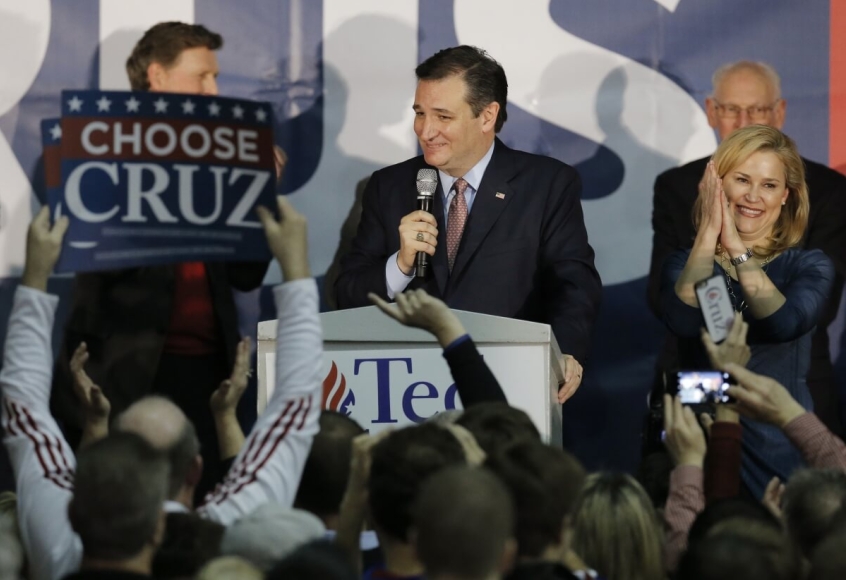

What alarmed me more than any of this, though, were the words he used in a speech after his Iowa victory. He said: "While Americans will continue to suffer under a president who has set an agenda who is causing millions to hurt across this country, I want to remind you of the promise of Scripture. Weeping may endure for a night, but joy cometh in the morning. Iowa has proclaimed to the world, morning is coming."

Ridiculously unfair to Obama? Of course, though this is politics. Self-aggrandising nonsense? I'm sure Iowa is lovely, but "morning is coming" anyway, thank you.

But what ought to set alarm bells ringing for everyone who cares about Scripture and truth is the way Cruz co-opts the Bible for his campaign and twists the eternal, inspired words of Psalm 30 to refer to his own victory in a political skirmish.

This has been the hallmark of the Republican campaign so far: that the candidates have had to play for the evangelical vote by identifying their own visions and characters with what they believe evangelicals want. And the ones who've got the most votes have been the ones who've been best at it. They have, as Ed Cyzewski points out, succeeded in identifying their own political programme with a set of particular values held largely among the evangelical constituency.

In other words, they and their fellow culture warriors have corrupted faith. They've made it co-extensive with their politics and their culture. For a country in which the separation of Church and State is a constitutional requirement, that's extraordinary – and extraordinarily terrifying. It amounts to politicians declaring the content of a religious faith and committing themselves to a programme that enforces it. Listen to the rhetoric, and it's arguably not far off from the Christian version of Iran and Saudi Arabia.

This results from a fundamental theological error, and one that's taught and reinforced from evangelical and other pulpits everywhere. The assumption is that we should campaign as Christians on particular issues, and vote as Christians. We work out our discipleship as Christians by our action in society, and part of that is taking up particular positions on particular issues.

But it's not like that at all. We hold opinions as Christians only on the issues on which the Church has pronounced – its dogmas and doctrines. Our Churches might pronounce on other things, like the need to help refugees or to combat racism. We are wise to listen, though we may dissent; we might stretch a point and say, if we like, that as Christians we want our government to accept more Syrians into the country.

But when it comes to political programmes, we hold these views as ourselves. We might be Christians, but we don't speak for the Church, and the Church – or any wing or tendency of the Church, like evangelicalism – doesn't speak for us. We hold the views that we do because of our thinking, our conversation, our reading and the views of people around us. Our Christianity – the teaching of Scripture and the communal life of the Church, our prayers and devotions – is the lens though which all these things are focused and become a belief.

So our Christian faith critiques every kind of politics and every politician. It doesn't allow any system or individual to speak for it. It rejects with horror any attempt to appropriate it for unworthy ends. In Britain we've seen this quite nakedly expressed by the far-right Britain First's so-called 'Christian Patrol' through multi-religious Luton. For them, 'Christian' has become a term of exclusion, designed to set 'us' against 'them'. But no individual and no system is right, because none of them is the Kingdom of God. The best we can say is that some of them are less wrong.

To the extent that evangelicalism has been co-opted for political ends, it's been corrupted. Some of its representatives have been sucked into endorsing candidates by political operators ten times smarter than they are. Others don't realise how the language they use favours one side. They've lost sight of their calling, which is to preach Christ crucified.

This campaign will drag on for months, and candidates will continue to regard the evangelical vote as significant. They'll take Christians up a mountain and show them all the kingdoms of the world and their splendour. "All this I will give you, if you will bow down and worship me," they'll say.

How will this temptation story end?

Follow Mark Woods on Twitter: @RevMarkWoods