Hebrew scholar and Jewish academic Irene Lancaster explains the meaning of Pesach and the Seder for Jews:

In his Easter message, the King said: ‘The love [Jesus] showed when he walked the Earth reflected the Jewish ethic of caring for the stranger and those in need…’

This is a reminder that the Pesach week that we are just celebrating, ending on Monday night, would have been celebrated annually by Jesus and his family, with always room for one or two guests.

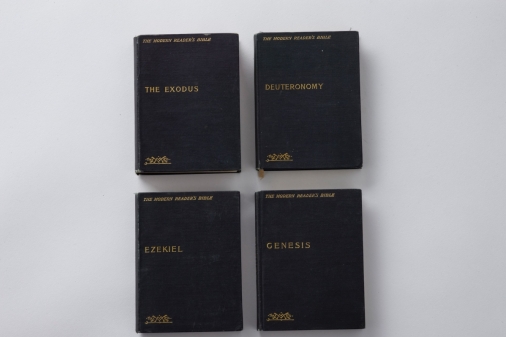

The Seder commemorates many things, but mainly the Exodus of the Jewish people from Egypt, which took place around 3500 years ago, in 1440 BCE.

This Pesach has been unusual in falling on Saturday night, straight after Shabbat HaGadol, the Great Shabbat. On this day, the last chapter of the last Hebrew prophet, Malachi, is read (3:4-24 in the Hebrew version).

Here Malachi announces the great and terrible Day of the Lord, preceded by the coming back to earth of the prophet Elijah, whose mission is to reconcile children to their parents, in order to prevent total devastation.

This is a strange intervention which perfectly describes the family Seder and all its dynamics. And during the Seder, as well as the four cups of wine we drink, an extra cup is poured for the prophet Elijah, who is expected during the night, and the next day the Elijah cup is mysteriously found empty.

On Sunday morning our first sermon also featured Elijah, but this time in 1 Kings 18:21. Here he is on Mount Carmel, facing the prophets of Baal, with the now proverbial question: ‘how long will you halt between two opinions?’ The word for ‘halt’ is ‘psach’ which, as well as meaning ‘pass over’, (as in Exodus 12), also signifies ‘limping along’ or ‘sitting on the fence.’ Will the people chose to abandon Baal completely, or continue to follow him when it suits them? Are they capable of making up their minds?

In similar fashion, will the slaves ‘skip and jump’ into their new role as free people, once G-d passes over their homes and spares them from the slaying of the first-born Egyptians, or will they sometimes revert to their former slavish attitudes and ‘drag their feet’?

We see that on their 40 year journey to the Promised Land the freed slaves often hark back to the good old days in Egypt, where they were at least told what to do and didn’t have to make decisions for themselves.

This is what we remember at the Seder Table as we narrate the story of our Exodus, using the Haggadah, which means ‘the telling’. This is where families are brought back together again, as anticipated in Malachi’s final prophecy and discuss our people’s story.

Pesach always takes place in spring, usually in April, as this year. In 1922, as Hitler wrote ‘Mein Kampf’, calling for the destruction of the Jewish people, TS Eliot published his poem, ‘The Waste Land’, which includes the line: ‘April is the cruelest month … mixing memory and desire.’ Something can be said for this description. April in Israel can be boiling hot, with dry, hamsin winds, but also cold, stormy and even snowy. The UK weather, if more temperate, is also unpredictable at Pesach time.

But nevertheless, the French Bible commentator, Rashi, (1040-1105), interpreting Exodus 13:4, states: ‘See how kind G-d is. He took you out in a month that is suitable for venturing out, that is neither too hot, too cold, nor too rainy.’

Incidentally, Rashi’s home town of Troyes in the Champagne wine area of France, is currently forecasting rain for the week, so he obviously spoke from personal experience!

But maybe Robert Browning summed it up best. In 1845, from northern Italy, where he had made his home, he wrote of his nostalgia for England:

‘Oh to be in England, now that April’s there,

And whoever wakes in England

Sees, some morning, unaware,

That the lowest boughs and the brushwood sheaf

Round the elm-tree bole are in tiny leaf,

While the chaffinch sings in the orchard boughIn England -now!’

No surprise, therefore, that at the end of the festival we read the Song of Songs, also celebrating the onset of spring and its manifestations in nature.

So, as we batten down the hatches, following the advice of the Met Office, let us cherish all those fine April days that live up to the springs that might be. And let us ponder the first Exodus of the Jewish people, taking place 3,500 years ago, in conjunction with so many others around the world.

The spring month of Aviv (also known as Nisan) is ‘the first of the months’, and therefore symbolizes death and resurrection - the death of slavery and the rebirth of the Jewish people, as well as hope.

During the 3,500 years of our existence as a people coming out of slavery, we have never once forgotten that we were slaves, and that only miracles and divine interventions have pulled us out of our torpor until we truly ‘become a free people in our own land,’ as well as ‘a light unto the nations’.

Naturally therefore, at Seders all round the Jewish world, families have been remembering the hostages, as well as all those brave people, Jews and non-Jews alike, who did their utmost to free them and will carry on doing so.

As the King said today: ‘The love [Jesus] showed when he walked the Earth reflected the Jewish ethic of caring for the stranger and those in need ….’