Work starts on two new Bible translations

Wycliffe Bible Translators havs started work on Bible translations for two languages in Chad that have no writing system.

The charity said it would be a "long process" to translate the Scriptures for the Mulgi and Gula Iro people groups.

There are only around 5- to 7,000 Mulgi, while the Gula Iro number between 10- and 11,000 people.

Preparatory research is being carried out by linguists Dorothea Reuter and Maria Gustafsson to lay the ground for translation and literacy work.

They have been researching the languages since the summer and have already created a draft alphabet chart for each one.

"We began our assignments at the end of June," said Dorothea, who will focus on Gula Iro.

Maria, who is focusing on Mulgəni, the language spoken by the Mulgi people, said: "We will partner with other organisations, working towards an oral Bible translation which at some point will be written down as well."

An indication of the challenges ahead, Wycliffe Bible Translators said it was not even known how, where and when the languages were used.

"That will be part of our research," said Maria.

"We know that Mulgəni is not well known, except by immediate neighbours. Gula Iro does have some written literature, and we know that for the Gula Iro their language is a key part of their identity."

The translation project is not only significant in providing Scriptures for these people groups; it's a milestone for the languages themselves.

Caroline Tyler, Wycliffe's team director in Chad, said: "It's such a privilege for our team to start working with these two people groups.

"Of course, we want them to have the Scriptures in their language so they can hear and read about Jesus in the language they understand best.

"But the Mulgi and Gula Iro will obtain so many other benefits from having their languages formally studied, written down and taught."

Meetings have already been held with representatives of the Mulgi and Gula Iro communities in the capital, N'Djamena.

Caroline continued: "We visited representatives of each community in the capital, N'Djamena, to explain the work and to hear from community members about their aspirations and concerns for their language."

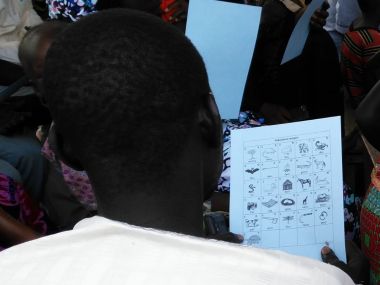

The draft alphabet charts presented during the meetings generated positive responses from those present.

"People get enthusiastic about this simple document as it's often the first written material they've seen in their language and they immediately want to provide feedback, give corrections and make suggestions," said Dorothea.

"In both instances it led to some lively interactions," she continued.

"The chart sparked considerable interest in the Mulgi meeting as everybody wanted a copy; people were fascinated as one of them read the words out loud. At the end of the meeting they were singing in their language and dancing."

French and Arabic are the two official languages in Chad, but many members of the Mulgi community do not speak either of them or only know enough to hold down a basic conversation, Dorothea said.

At school, this creates additional challenges for the children as lessons are taught in French. Many in the communities have attended school for only a few years; some have never been at all, and so levels of education and literacy are low.

Dorothea is optimistic that learning to read and write in their own mother tongue for the first time will help to reverse these trends.

"The work will benefit the whole community, not just the Christians, who are a minority," she says.

"Writing down a language shows it has a value. It also helps to keep knowledge about the history of a people – their traditions, culture, and stories.

"If children can learn to write and read in their own language first, it will help them then to continue with French later in school."

In terms of the work ahead translating the languages, she said she was relying on God for his help.

"First, we need to figure out what sounds there are in the language, and how they affect the meaning of a word. Then how many letters we need in the alphabet and which letters to choose – and how to represent in the written language everything that is important in the oral language," she said.

"It's exciting to start this work, to work directly with the people, and to do something that no one has done before or very little. It's also challenging, because there is so much to do and you can't look up 'the right answer'.

"It's definitely something I need God's wisdom and strength for and I can't do on my own."