A dialogue between a Christian and a Jew on Lent

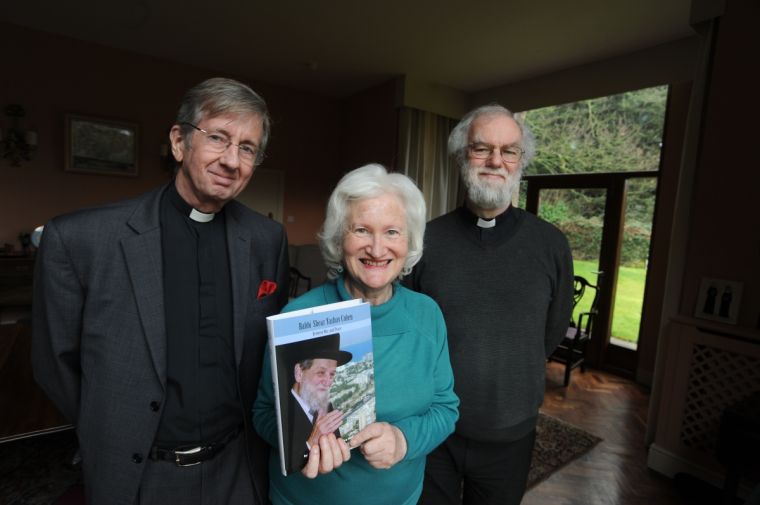

Former Archbishop of Canterbury Dr Rowan Williams and Jewish academic Dr Irene Lancaster, author of 'Deconstructing the Bible', discuss the history and meaning of Lent as a hopeful bridge between Christians and Jews.

The two of us have been involved in dialogue for just over 10 years, though we first met in Liverpool in 2002, not long after Rowan was named as Archbishop of Canterbury. During his tenure at Canterbury, Irene, who was living in Israel for part of this time, played a significant role in encouraging direct dialogue between the Church of England and the Chief Rabbinate of Israel.

We share concerns about persisting and increasing levels of antisemitism in our society. In the past decade, Rowan has been involved in highlighting the problem of antisemitism in the UK, including the plight of Jewish students at British universities while he was Master of Magdalene College, Cambridge University. In 2016, this led to the first ever payout to a Jewish student by York University, followed by a second payout in 2020 to another Jewish student at SOAS.

But we see the situation in the Church of England (and other Christian bodies) as still giving cause for real anxiety. Signs of hostility towards Jews and profound ignorance of Jewish faith, practice and history are in evidence. Stereotypes are unthinkingly repeated in a range of areas, with Jewish identity being associated with materialism, misogyny, and legalism, with a misleading contrast between an 'Old Testament' religion of law instead of love and the Christian gospel.

Intentionally or not, this impacts damagingly on perceptions of contemporary Judaism and feeds the negativity of the media towards Jews and Judaism. Many Christian ordinands have alarmingly little knowledge of Hebrew Scripture, the realities of Jewish history, and modern Judaism, while some of the language used by Christian leaders around the issue of Israel and Palestine continues to echo centuries-old language about Jewish blood guilt.

In 2019, we wrote a joint article setting out to rectify what some saw as the imbalance of the recent Church of England document on relations with the Jewish community, which readers can find here.

Lent, which Christians are observing at present, is a season with difficult associations for many Jews. Irene recalls her mother's memories from Poland of the long history of pogroms and massacres, and of hiding in the house to avoid assaults by Christian zealots out to avenge the 'blood of Christ' around the Lent and Easter seasons.

These are the concerns that continue to drive our dialogue particularly at this season of the Christian year. That is why we are exploring together the history and meaning of Lent, and especially Jesus' quotes from Deuteronomy during his forty days' fast in the desert.

Irene: What is the origin of the word 'Lent'?

Rowan: 'Lent' derives from the Anglo-Saxon word for 'springtime'. In Latin-influenced languages (including Welsh for these purposes!), the name is one or other derivative from the Latin 'quadragesima' - 'forty' (so 'Careme' in French, 'Carawys' in Welsh, and so on) - recalling the forty days' fast of Jesus in the desert before he begins his ministry as a teacher and healer.

Irene: When and where did the period of Lent begin as a discipline of the Church?

Rowan: It's not easy to say exactly when it began as an annual discipline. We know that in the early centuries all members of the Church were encouraged to fast and pray alongside those preparing to be baptised; and since it became common to baptise new converts at Easter, it was a natural step to have a general fast in the weeks leading up to Easter. This had become widespread by the fourth century.

The sequence of the Christian year, moving from Christmas to Epiphany (which includes the commemoration of Jesus' baptism) must also have made it natural to associate the long fast after the Epiphany season with Jesus' long fast after his baptism. The stories of Jesus' time in the desert include stories of his refusal of the three great temptations of the devil (all of them, as we'll see later, repudiated with words quoted by Jesus from Deuteronomy), so it becomes another obvious development to associate the period with self-examination as well as literal fasting. Hence the custom of making a confession before or early in Lent - ideally on Shrove Tuesday, the day when you are 'shriven' and receive absolution for your sins after confession.

Although the custom of baptising at Easter fades away (as there are fewer converts and more children born into the Christian community and so baptised as infants), the fast continues, and even survives the Reformation in Anglican and Lutheran churches.

It is signalled outwardly by the removal or veiling of some church decoration and the use of vestments either in sombre colours or in plain or coarse material, by the general prohibition of marriages during the season, and by the omission of the festive 'Alleluia' from all liturgical ceremonies.

The Lenten season technically ends on Maundy Thursday evening, but the fast is supposed to continue till the first Mass of Easter, usually in the late evening of the Saturday before Easter Sunday - sometimes at midnight, or in the very early morning. All this is Western Christian custom.

The Eastern Church is a bit different - no Shrove Tuesday, no ban on Alleluia, but a much stricter set of fasting rules (e.g. no dairy products), and a set of prescribed and very lengthy hymns to be sung each week. But a midnight Easter celebration, very lengthy and festive.

Irene: Could you say a bit more about Jesus' quotes from the Hebrew Book of Devarim, which Christians call Deuteronomy?

Rowan: When during Lent Christians remember Jesus' forty days in the desert, they hear how Jesus resists three temptations from the devil. In each case, Jesus replies - very significantly - with words from Deuteronomy, words expressing the heart of God's purpose in giving Israel the Torah. He says that we do not live by bread alone but by the words that come from the mouth of God; that we must not put God to the test (i.e. we must not try to make God prove himself to us by giving us what we think we want); and that we must worship and serve none other but God - all of these quotations from Deuteronomy 4, 6 and 8, a key section of the Torah in defining what the calling of Israel is.

In other words, Jesus deliberately identifies himself with that calling as it is spelled out in the Torah: he is living out the vocation given to all of Israel. During Lent, for those Christians who use a regular lectionary scheme of daily readings, we move from Genesis through to the story of the Exodus, so that we are reading about the Exodus itself and the crossing of the Reed Sea around the time of Easter. This is because the death of Jesus, which took place at the time of the Passover celebrations, is seen as having the same meaning as the sacrifice of the Passover lamb, marking God's act of deliverance and God's faithfulness to his covenant.

In Luke's gospel, Jesus' death is itself referred to as an 'exodus': he is living out the history and experience of God's people. It's a reminder that the gospels do not suggest that Jesus intended to found a new 'religion': as in his responses to the devil in the desert, so in his understanding of his death, he sees himself as restoring the integrity of Israel, deepening the awareness of the covenant.

Christian writers like Paul explore what they think are the implications of this for non-Jews, but the history of Jesus is clearly the history of someone whose mission began with his sense of being called to gather and renew the Jewish people, according to their original vocation in the exodus and at Sinai.

Irene: So, just to make this clear, the three key texts for Jesus in the desert are taken from the early books of Devarim, known as the Sedras of Comfort, and accompanied in the late summer before the autumn festival which ushers in Jewish New Year, known as Rosh Hashana, by Haftorahs from the consoling books of Isaiah chapters 40-51? I find this very interesting, as the book of Devarim is often mocked and ridiculed in the mainstream media, including very recently by the BBC, as well as in the Church press, for which I have actually written a number of articles - but they never seem to learn.

So are you saying that Jesus wasn't intent on starting a new religion per se, but actually in living a Jewish life to the best of his ability, and that this type of living is worthy of emulation by Christians (including members of the C of E who I find so dismissive of Jewish identity and integrity) - looking to the words of God for sustenance, trusting God and not putting him to the test, worshipping him alone? If this is the case, why is antisemitism so prevalent during the period of Lent, leading up to the major festival of Easter?

Rowan: Some (not all) early Christian writers will contrast Christian fasting with Jewish - the one being supposed to be more sincere than the other, with the usual complaint about Jewish piety being more 'external' or legalistic. Historically this may contribute a bit to anti-Jewish feeling in Lent. These days, it still gets recycled unthinkingly in the contrast between legalistic religion and its opposite; people don't notice that the tension is there in Hebrew scripture itself - it isn't a Jewish/Christian difference. There were historically places (including Rome) where Jews were forced to listen to Christian sermons in Lent and at other times (up to the 19th century), in the hope that they would be ready to present themselves for baptism at Easter.

And Holy Week has often revived anti-Jewish feeling because of the misreadings of the gospel story. Despite everything, the liturgical recitation of the passion story requires the Christian congregation to say or sing the words of the High Priests ('Crucify him' etc.) - so that the responsibility is ours not someone else's. But that isn't always obvious, to put it mildly.

Irene: Yes, I have written about the phenomenon of Jews being forced to hear compulsory sermons in Rome, which was witnessed to his disgust by the greatest Victorian English poet, Robert Browning, and which I have written about here. Incidentally, Browning was the first to conclude that the Jews would one day regain their home in Israel and begin to fill their role as a 'light to the nations'. It's all there in the poem.

Looking to the future, is there a possibility, do you think, that Lent could be approached by the C of E and her adherents in a new way that is more open to the Jewishness of Jesus, such that the safety of Jews in this country is not impaired at this time of year, but obviously without a conversionary agenda?

Rowan: I think the beginning of an approach to Lent that is more open to the Jewish voice and presence would be to stress that the story of Jesus' temptations in the desert is meant to show him being the perfectly obedient Jew: he is presented in these traditions as fulfilling the demands of Torah - living from the Word of God, not putting God to the test, refusing worship to any other than God.

So his public mission begins with this recalling of God's people to their original loyalty, and this is shown by his quotation of the Torah texts that define his own obedience. We as Christian believers are invited in various ways (especially in the opening psalm of morning prayer each day in the old Prayer Book) to identify with the people in the desert, tempted and often complaining; testing or provoking the Almighty. Jesus is obedient where we are disobedient - we are no better than the rebellious people in the stories of the desert wanderings.

But God did not finally reject them despite their disobedience: he listens to Moses' prayer for the people and Moses' willingness to suffer for them, and so we believe that God listens to the prayer and obedience of Jesus for us too. That might be a start, if I were preaching on Lent with the intention of steering it away from false discontinuities between Judaism and Christianity.

Irene: Rowan, thank you very much for teaching me a great deal that was new about Lent. Particularly the point that in his time of trial, Jesus remains Jewish and actually quotes from Devarim (Deuteronomy) the final book of the Torah (Pentateuch), which most Jewish scholars agree is the most wonderful book of the Hebrew Bible, is definitely a cause for celebration and hope.

To coin a phrase, this dialogue gives a great deal of 'food for thought', as Jesus would no doubt describe it were he alive today. And I look forward to a similar dialogue session in a couple of weeks' time as we lead up to Easter, straight after the festival which Jesus himself would have celebrated in commemoration of the exodus from Egypt - our very own Pesach Seder.