Armenians say goodbye to their churches in Nagorno-Karabakh

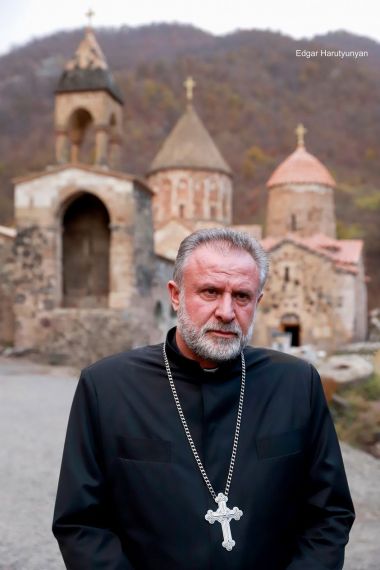

It was a dire day for Father Hovhannes when he learned that the medieval Armenian monastery complex Dadivank in Nagorno-Karabakh would now go under the control of Muslim-majority Azerbaijan. The region of Qarvachar where the monastery is located would need to be vacated from Armenians within days.

Nagorno-Karabakh is a small, mountainous, landlocked area in the South Caucasus lying between Armenia and Azerbaijan, bordering Iran to the south. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Nagorno-Karabakh with a majority-Armenian population remained a disputed territory between the two post-Soviet countries. The two-year war came to a halt in 1994 with an indefinite ceasefire and Nagorno-Karabakh went under ethnic Armenians' control.

The new phase of the war lasted 44 days, ending in November of this year. Large parts of Nagorno-Karabakh passed into Azerbaijan's control and Russian peacekeepers were placed in the region for five years.

The military conflict ended with the fall of Shushi, a town overlooked by the 19th century Cathedral of the Holy Saviour. When the Azerbaijani army entered the town following the ceasefire signed on the night of 9 November, the cathedral was one of their first targets: the inner and outer walls were immediately vandalised by graffiti. The cathedral had already been heavily shelled and extensively damaged by the Azerbaijani Army, which among its militants had thousands of Syrian Jihadist mercenaries.

The early 19th century Church of St John the Baptist in Shushi saw its domes destroyed during the war, while the Church of Saint Mary built and consecrated more recently in the town of Mekhakavan was shelled and almost completely demolished.

Armenians in the region fear that their ancestral Christian heritage is now threatened under Azerbaijan's control. Father Hovhannes, the Abbot of Dadivank, says these fears are well-founded: in 1993, when Armenia won control of the territory, they discovered Dadivank and other holy sites desecrated. The walls of their churches and chapels bearing frescoes, engraved crosses and Biblical writings in the Armenian script had become shelters for animals.

"On 3 April 1993, after the liberation of Qarvachar and Dadivank, I was one of the first people who entered the monastery with the soldiers," Father Hovhannes recalls.

"It had been turned into a barn for animals. The interior was badly damaged. We started cleaning and restoring it. I washed all the engraved crosses myself. Thanks to many donations, Dadivank started thriving again!"

The first chapel of the monastery was founded in the 1st century by St Dadi who was the pupil of Christ's disciple Thaddeus. As Christianity spread in Armenia and was adopted as a state religion in 301AD, Dadivank kept growing over time and was completed in the 13th century. The grave of St Dadi was discovered under the holy Altar of the main church in 2007.

Surrounded by picturesque natural scenery, Dadivank is one of the symbols of the Armenian Christian heritage in Nagorno-Karabakh. Over the centuries it has withstood numerous attacks and remained one of the most-cherished holy sites for Armenians for pilgrimages, baptisms and marriages.

Father Hovhannes declared that despite security concerns, he was not going to leave the monastery, but would stay and ensure the holy site was not desecrated. He was soon joined by other clergymen from other churches.

Thanks to the efforts of the high-ranking Armenian religious leaders, Dadivank came under special protection of Russian peacekeepers. Armenians, however, were not consoled, knowing that this is only a temporary arrangement. They flocked into the monastery in hundreds to light a candle, pray and receive Father Hovhannes's blessings before the entire territory went under Azerbaijan's control.

Outside the monastery, Father Hovhannes was joined by Baroness Caroline Cox, a strong supporter of self-determination for the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh.

"I have seen cathedrals badly damaged by bombs," Baroness Cox said. "It breaks our heart to be here today. We weep with you, but we want to say thank you to the people of Armenia and Artsakh (the Armenian name of Nagorno-Karabakh) because you have held in the frontline of faith and freedom, for the rest of the world."

The Christian heritage in Nagorno-Karabakh consists of churches, monasteries, chapels, cross-stones, frescoes, engraved religious writings dating back to the earliest stages of Christianity. The Department of the Armenian religious and cultural heritage of Nagorno-Karabakh at the headquarters of the Armenian Apostolic Church estimates that more than 100 pieces of this heritage are now transferring under Azerbaijan's control.

Fears that the Armenian Christian heritage will be eradicated under Azerbaijan's rule are partly based on the events in the Azerbaijani enclave of Nakhichevan.

Rene Levonian, an Open Doors spokesperson, said: "One hundred years ago the two-thirds of the population of Nakhichevan were Armenians. Today there are no Armenians there and the entire Armenian Christian and cultural heritage is almost non-existent. Thousands of ancient cross-stones – large rectangular stones with carved crosses – and hundreds of churches have been systematically subjected to vandalism and destroyed. It's why Armenian Christians have little hope for preservation of their heritage."

Following the recent war, evidence has started to surface of mass vandalism and desecration. Mobile phone footage and photos show churches and cathedrals badly damaged by shelling and vandalised with graffiti.

Other mobile phone footage shows troops – a mixture of Azerbaijanis and Syrian jihadist mercenaries – standing on church roofs shouting "Allahu Akbar". Armenian Christians reportedly exhumed coffins of their loved ones prior the expected arrival of Azerbaijani troops, fearing the worst.

Father Geghard Hovhannisyan is the Abbot of the ancient Amaras monastery, which was an education hub founded in the 4th century. The monastery was home to the first school where the newly invented Armenian script was taught in the 5th century. Father Geghard found it looted when he returned following the recent truce.

"It is very painful because the Azerbaijani militants have managed to enter the monastery," Father Geghard said. "The frescoes and many other valuable items are missing."

After negotiations, Amaras may remain under the Armenian control, but he fears that he will never see the artifacts again.

And as other Armenians load their belongings into trucks and vacate their villages and towns, it adds to the pain to say a final goodbye to their churches that are part of their identity, fearing what will become of them.