Charlie Charlie game should challenge us to take the supernatural more seriously

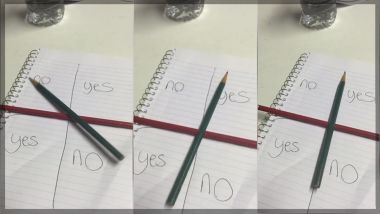

The Internet's love of viral crazes stumbled into supernatural territory when the 'Charlie Charlie' Challenge became massively popular among young people. The game involves crossing two pens or pencils on top of a piece of paper, creating four quadrants with either 'yes' or 'no' written in them. Players then ask questions of a Mexican 'spirit' named Charlie, and wait for him to answer the questions by moving the pens.

Exorcists are warning that teenagers are messing around with forces way beyond their understanding, with one telling the Catholic News Agency that players are 'calling on spirits' which 'will stay around for a while' after the game is played. They suggest it's just a simplified version of the notorious Ouija, which has seen young people dabble in the occult for generations.

For many, this is all harmless – if morbid – fun. Their line would be that evil spirits aren't real and the resulting phenomena can be explained away scientifically. But if that's true, why is the trend quite so fascinating? For years now, researchers have argued that while young people are largely no longer religious, they are spiritual, and they don't struggle to believe in a world beyond the visible. So when the #CharlieCharlieChallenge trend enticed thousands of teenage social media users this week, its spread can be partly attributed to the belief that it might actually be real.

As Christians, we believe this is serious. Actually asking an evil spirit, or a demon as he's variously referred to, to engage with us directly is playing with supernatural fire. The Bible talks about demonic forces often: Jesus casts them out of people; Paul warns not to 'participate' with them (1 Corinthians 10:20); and James says they believe in God – and shudder (James 2:19). In the Old Testament, God and his prophets are frequently warning Israel not to get involved with those who practice the occult, from Deuteronomy 18's list of 'abominable practices' to the grisly description of demonic sacrifice in Psalm 106.

That's not why young people are interested however. They're intrigued because they've seen one of those pencils move on a YouTube video, or heard a story about a demon who might be real, and can prove his existence. When they 'play' however, they're entering the world described in all those verses.

For some, like those Catholic exorcists, who report that "the number of disturbances of extraordinary demonic activity is on the rise," this is tantamount to a pastoral emergency.

Whatever your view on that, there are some interesting reflections to be drawn from this week's bizarre craze. As a youth worker, I'm fascinated that while teenagers seem to be interested in the idea of talking to an invisible spiritual figure who can give them some kind of guidance, they're choosing a Mexican demon over the Son of God. Why is that? Why when young people are so naturally intrigued by the supernatural, do they default to a magical way of supposedly contacting the dead, rather than wanting to contact a spiritual force who's very much alive?

Perhaps it's because we've sanitised Jesus; drained all the thrill and excitement out of him. The real, living Jesus was a genuine revolutionary with superhuman powers. He fought the religious, undermined the oppressive, and started a movement that now numbers 2 billion people. He battled demonic forces and won, sent shockwaves rippling through communities as he healed those who'd been sick and forgotten for years, and he even raised the dead to life. He was Martin Luther King and a couple of the Avengers, all rolled into one. But is that the Jesus we're showing to our young people? Do they know and understand how powerful he was – and still is? Do they even get to see a person controversial enough that people would want him dead?

If not, then it's hardly surprising that he's overlooked when a craze offers direct communication with a powerful supernatural force. That's just not how Jesus is seen by the majority of young people.

And if we're honest, is it even how he's seen by us?

Two years ago at the Youth Work Summit, pentecostal minister Celia Apagei-Collins used a shocking device to teach a memorable lesson. She asked the 1000+ delegates at the event to link hands, and then explained that we were going to hold a kind of seance; that we were going to "start asking satan to come". There were shrieks of protest from the crowd as the word's left her lips, so she explained herself. "Do you know why we don't want to ask Satan to come?", she asked. "Because we believe he'll come." Her real point: that while we believe Satan would come if we asked, we lack the same faith that God will answer when we call on him. (You can watch that moment here at 4 mins 30 secs).

So perhaps we too are more convinced about the power and influence of a demon than we are about the power of our God. That's a serious challenge of course, and it's one that makes little sense. As Rev Celia was suggesting – God and his enemy are two sides of the supernatural coin; in a fallen world, the one hints strongly at the existence of the other. Yet our fear of one seems to be stronger than our faith in the other; perhaps that's why so many Christians have expressed concern over Charlie Charlie.

The good news in all of this – especially for those who've played Charlie Charlie and now feel concerned about what might happen as a result – is that whatever demonic influence might be involved in the game, it's terrified of Jesus. Witness the horror of the demons in Matthew 8 when they come face to face with him, or their madness as they depart from those around him in Luke 4:41. They try to cry out "you are the Son of God", and yet such is his power over them, he even calls them to silence. The name of Jesus – that radical, living, spiritual master – is far more powerful than any demon, and can be called upon by anyone struggling with fear.

Perhaps then there's a more positive challenge to draw from this craze, alongside those genuine and understandable concerns about what young people are opening themselves up to. I know that intellectually I believe in the power of God, and yet I naturally fear the power of the enemy. Maybe it's time to put those intellectual beliefs into action; to call on the still-all-powerful name of Jesus, and expect the supernatural to break out all around us.

Martin Saunders is a Contributing Editor for Christian Today and the Deputy CEO of Youthscape. He's also one of the hosts of the Youth Work Summit on June 20th. You can follow him on Twitter: @martinsaunders