God without church: Why churchless believers don't do much for Christianity

The Victorian prime minister Lord Melbourne, not a great churchgoer but a great wit, used to say: "While I cannot be regarded as a pillar, I must be regarded as a buttress of the Church, because I support it from the outside."

New research by the Church of Scotland claims to show there are a good number of Lord Melbournes about today.

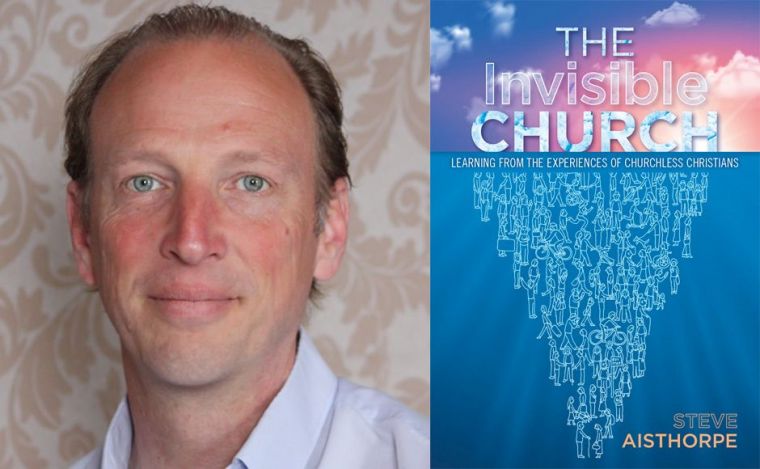

The Invisible Church, to be published next month, claims the Christian community in the UK is much bigger than it seems. Modern Christians are turning to the internet and other less formal surroundings to practise their beliefs, it says. Around two-thirds of those who stop attending church maintain a strong personal faith afterwards.

Author Steve Aisthorpe said: "I found that changes in wider society and in the practices of Christian people mean attendance at Sunday morning worship can no longer be seen as a reliable indicator of the health and scale of Christian faith."

And, he said, people leave for a variety of reasons. "There has been a well-publicised view within the Christian community that those who discontinue church attendance usually do so over trivial issues and it is now clear that this is not true. The evidence also shows that churches which are resistant to change and those which are dominated by a single group are more likely to decline."

So while the Church is declining, it's not declining as much as all that; there are plenty of Christians operating below the radar. And there are plenty of 'Fresh Expressions'-type gatherings in small groups, not necessarily tied in to a denomination but lively and flourishing nonetheless.

It's an attractive and not unconvincing picture. The church which is seeing its congregation grow less month by month needn't worry too much. They might be lost to the church, but they are not lost to the Church. There are more Christians out there than we know. The whole secularisation thing is vastly overblown.

So why am I not as encouraged by this as I ought to be? Three reasons.

First, the whole 'churchless Christianity' thing is a contradiction in terms. Religion is done together or it is not really religion. Someone's private beliefs might be meaningful and precious to them, but they are still private. It's when they are activated by contact – perhaps uncomfortable, irritating or frustrating contact – with other believers that they become truly Christian. Religion that isn't shared is more of a philosophy than a faith.

Second, the institution of the Church, expressed in the little local fellowships that make it up and in the councils, synods and assemblies where they come together, is what makes it visible and influential. It's through our combined weight that we can influence debate and help shape public opinion. If the churchless Christians aren't part of that, they might be shining brightly enough in their little corners, but they are not being lights to the world.

Third, though, and most importantly: churchless Christians are using up the capital they've been given by their spiritual parents and grandparents (who are often their real ones too). They have the luxury of leaving the Church without leaving the faith because the Church has rooted the faith so deeply in them. But what about their children? Who will give them the spiritual grounding they had themselves? That doesn't come through private reading and thinking. It comes through learning the discipline of prayer and worship through turning out Sunday by Sunday, often when we have other things to do.

So, two cheers for the research. What it seems to say, from the headlines so far, is that the idea that people leave the Church because they have lost their faith or are hostile to religion in general isn't right. They leave because it doesn't work for them. If they're disillusioned, it's not with God, it's with the way the Church asks them to do God.

The answer is not, though, to lose confidence in the Church and imagine it has to be entirely reinvented. For most Christians it works very well. But it does mean that people need to be given the freedom to criticise, to be honest, and to feel they've been heard and that the Church will respond and change where it can.

And it means, perhaps, that churches can be less defensive about the world outside their doors. It's not full of enemies. It's made up, in good part, of people who'd like to belong if they could only be persuaded the Church was worth belong to.

Follow Mark Woods on Twitter: @RevMarkWoods