Despite good progress, the UK is still a long way from 100% low-carbon energy

In the past ten years the UK's electricity mix has changed dramatically. Coal's contribution has dropped from 40% to 6%. Wind, solar power and hydroelectric plants now generate more electricity than nuclear power stations, thanks to rapid growth. Demand for electricity has also fallen, reducing the country's dependence on fossil fuels. Thanks to these three factors, the carbon intensity of Britain's electricity has almost halved, from more than 500g of CO₂ per kilowatt-hour in 2006 to less than 270g in 2018.

Progress has been so quick that a fully low-carbon power sector in Britain has transformed from a faint pipedream into a real possibility, according to the CEO of one of the UK's "big six" energy companies. Indeed, the National Grid now expects to be able to operate a zero-carbon electricity system by 2025.

Already approaching that milestone on windy, sunny days, the country's first hours of 100% low-carbon electricity could soon be here – but staying at 100% throughout the year will be much more difficult to achieve. So what does the journey to decarbonisation look like?

Headwinds to decarbonisation

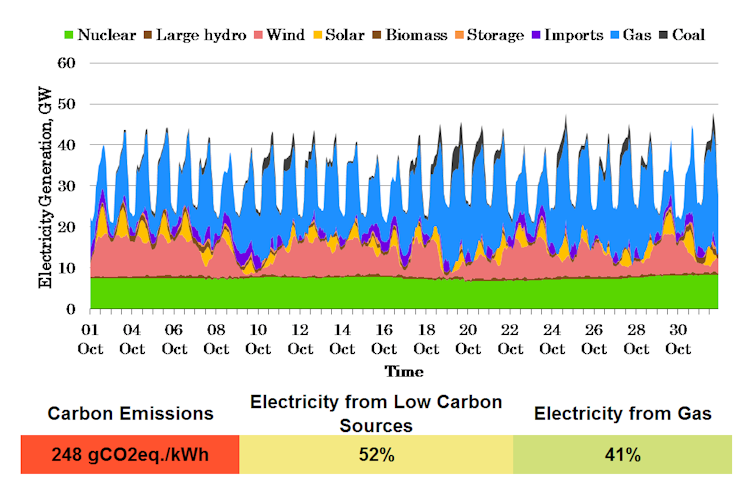

To paint the UK's energy future, it is important to first understand how electricity is generated today. The graph below is a visualisation of British electricity generation in October 2018. Periods of strong wind (in red) and sun (yellow) combined with nuclear power (green) meant that on some days, more than 75% of electricity came from low-carbon sources. With solar prices still decreasing and the government recently agreeing a major deal for offshore wind to produce one-third of the UK's power by 2030, the country's first hours of low-carbon power could arrive within the next five years.

British electricity generation in October 2018. (Dr Andrew Crossland/MyGridGB)

But the graph also highlights the other side to the UK's energy story. When the wind is weak and the skies dark, low-carbon sources provide less than 25% of electricity generation. On average, low-carbon technologies accounted for more than 45% of British electricity in 2018 – and almost half of that came from nuclear plants. Saying goodbye to fossil fuels quickly might mean accepting that the ever-controversial form of energy will play some role in the UK's electricity mix in the medium term.

Even with the aid of nuclear power, electricity consumption in Britain is set to increase dramatically in the coming decade. As electric cars continue their journey to the mainstream, traditional transport fuels will be replaced by electricity. The yearly energy demand of transport fuels is currently more than double the UK's national electricity consumption.

Similarly, plans to decarbonise the UK's heat generation – currently 66% is generated by gas – by converting to electric heating systems will also place huge pressures on demand. During winter months, heat can consume more than three times the daily energy demands of electricity – and over a full annual cycle it constitutes 50% of total energy demand. Collectively, these factors will move the goalposts for 100% low-carbon electricity further and further away.

Powering through

While the huge efficiency increase of electric vehicles over internal combustion engines should cushion the impact of electric vehicles on the UK's energy future, the country will need to diversify its energy mix as much as possible to bring those goalposts back into sight. This means continued growth in wind, solar, hydro, biomass, energy efficiency and energy storage to carry the country through the calm, grey days. Precisely how much growth is needed depends exactly on the future of energy demand, but to give some perspective of scale, more than 80% of the total UK energy supply, including electricity, land transport and heat, still comes from fossil fuels. The tens of billions of pounds already invested in low-carbon electricity is just the start of the UK's journey to decarbonised energy.

It also means seeking alternative, non-electric methods to replace fossil fuels in heat generation. Capturing waste heat from industrial processes, geothermal heat from the ground and heat extracted from water bodies could all limit demands on the electricity sector and make it easier to achieve more low-carbon heat and power. Southampton already heats much of its city centre geothermally – and many cities can and should follow suit. Recent work published by the BritGeothermal estimates that geothermal energy alone could meet the UK's heat demand for at least 100 years.

Concerted and sustained effort from both government and individuals is required if the UK is to achieve a low-carbon nirvana in heat, transport and power. State support of the renewables industry through ensuring long-term investment security and regulations to create energy-efficient and electricity-generating new homes will be essential in the UK's decarbonisation journey. The UK population will need to consume less energy individually, use energy more efficiently and use their voices and money to support renewable solutions. They will also need to elect representatives with a genuine ambition to decarbonise the country – rather than to commission new coal mines and fracking sites.

Large-scale changes are already in motion. Shell recently stated that it wants to become the world's largest electricity supplier and is among many oil giants investing heavily in renewables. While the need for new forms of energy presents big challenges for the UK it also offers a wealth of opportunities for the current generation to be part of an energy revolution. If the UK embraces the task, it could be joining Costa Rica, New Zealand and Norway as low-carbon powerhouses before the middle of the century. As one specialist at the start of his career and another nearing the end of his, we say bring that challenge on.

Andrew Crossland, Associate Fellow, Durham Energy Institute, Durham University and Jon Gluyas, Professor of Geoenergy, Carbon Capture and Storage, Durham University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.