Evangelical Christians much more politically engaged than rest of the UK

Evangelical Christians are far more politically engaged than the rest of the population, but share the general lack of trust in politicians, according to a new study by the Evangelical Alliance (EA).

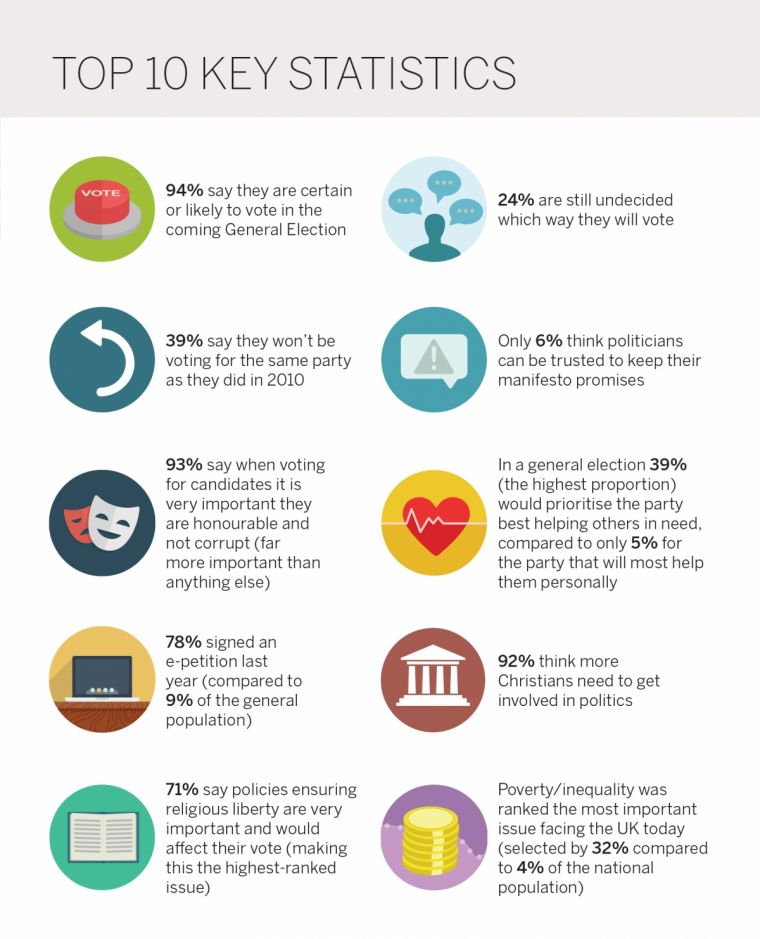

The vast majority of evangelical Christians are already convinced of the need to vote at this year's election. According to the EA's 'Faith in Politics?' report, 94 per cent of Christians asked said they would probably vote – 80 per cent said they were 'certain' to vote, and 14 per cent said they were 'likely' to. This is almost double the national population, of whom 41 per cent said they were certain to vote in the next election, according to a 2013 report.

But exactly how those votes will be cast is still unclear. Almost a quarter (24 per cent) said in the survey, which was conducted in August and September 2014, that they hadn't yet decided how they would vote.

One aspect that may be influencing this uncertainty is a disenchantment with politicians and political promises. More than half (60 per cent) of the 2,020 evangelicals surveyed said they had become less trusting of the government in the last five years and half said that they were less likely to believe what politicians say. About two thirds said that the recent expenses scandals had affected their trust in parliament.

Despite their reservations they about politicians, evangelicals are clearly politically engaged, and this engagement is not limited to the polling booth. Evangelicals are seven times more likely to have contacted a politician and taken part in a public consultation than the general population and 14 times more likely to have participated in a campaign. Additionally, 78 per cent of those surveyed signed an e-petition in the last year, compared to 9 per cent of the population as a whole.

The kind of political engagement demonstrated by Christians shows some alignment with what evangelicals think Jesus would do. When asked what Jesus would do if he lived in the UK, 82 per cent said he would protest against violence and corruption, 42 per cent thought he'd be put in jail, and just 4 per cent said he would stand for political office.

The report also stresses the difference between evangelicals' voting priorities and rest of the population.

Poverty and inequality ranks top of the list of concerns among evangelicals, with 32 per cent of people saying it was the most important issue facing the UK, compared to just 4 per cent of the rest of the population. Race and immigration is the primary issue nationally, according to a 2014 Ipsos Mori poll, with 21 per cent of the population saying that this is the priority for Britain, compared to 6 per cent of evangelicals.

In describing the three main factors that influence their vote, 39 per cent agreed they would vote for the party that would best help those in need regardless of the impact it would have on them personally.

The EA's advocacy director Dr Dave Landrum said: "Evangelical Christians are passionate about politics that works for the good of all of society, and when it comes to voting they're not going to be backing the party which just benefits themselves the most."

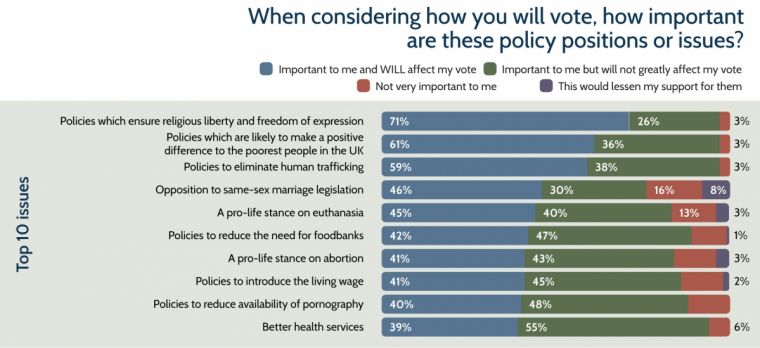

Respondents also said that policies ensuring religious liberties would affect the way they voted; 71 per cent said that this was an issue that would affect their vote, with a further 26 per cent saying that it was an important issue but not critical in deciding how to vote.

Almost half (46 per cent) said that opposition to same-sex marriage was an issue that would sway their vote.

"Many commented that the redefinition of marriage had badly damaged their view of politics," Landrum said. "It's time for politicians to rebuild trust with all voters, but in the coming months evangelical voters are likely to be wary of grand promises made by any of the political parties."

Unsurprisingly, these issues – poverty, religious freedom, marriage – are also among the main issues that have been spoken about publicly in churches in the past year. Almost a third of evangelicals (30 per cent) said they had been openly told to support or oppose a particular policy by their church, but it is clear that churches are not generally telling people how to vote – only 2 per cent of respondents said their church had told them to support or oppose a particular candidate.

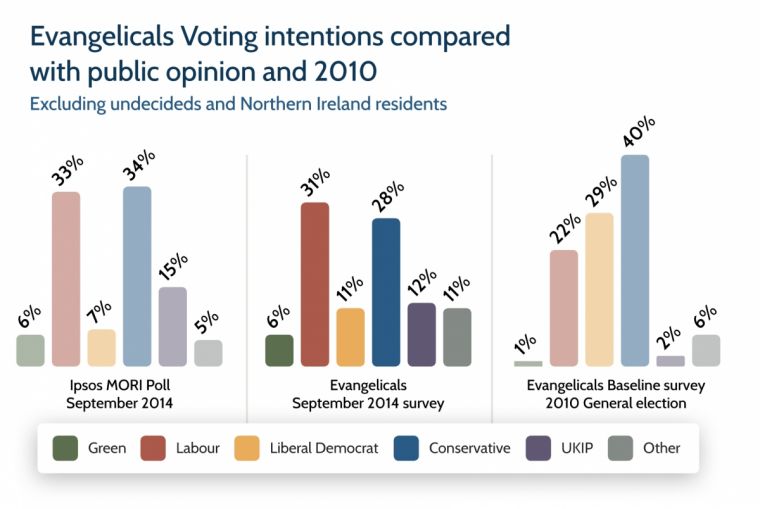

Although Christians prioritise different issues from the rest of the population, the change in party support is similar to national changes; support for UKIP and the Green Party has increased and Liberal Democrat support has declined. In the EA's 2010 survey, just 2 per cent of evangelicals said they supported UKIP, this is figure has now risen to 12 per cent.

Overall there is likely to be a slight shift to the left, as fewer evangelicals said they would vote for the conservatives than in 2010 and there is a rise in the number planning to vote for the Labour Party.

There is also more scepticism about the combination of faith with Conservative Party views, as 22 per cent said they found it hard to understand how someone could be a Christian and vote for the Tories. Only 9 per cent of those asked said the same about the Labour Party.

A majority (59 per cent) of those surveyed expressed a sense that none of the parties represented their Christian views. And despite the already high levels of political engagement among evangelicals, 92 per cent said they thought more Christians should get involved in politics.