Evangelicals And Martyn Lloyd Jones: Fifty Years Later The Debate Rages On

October 18, 1966, marked a defining moment for British evangelicals.

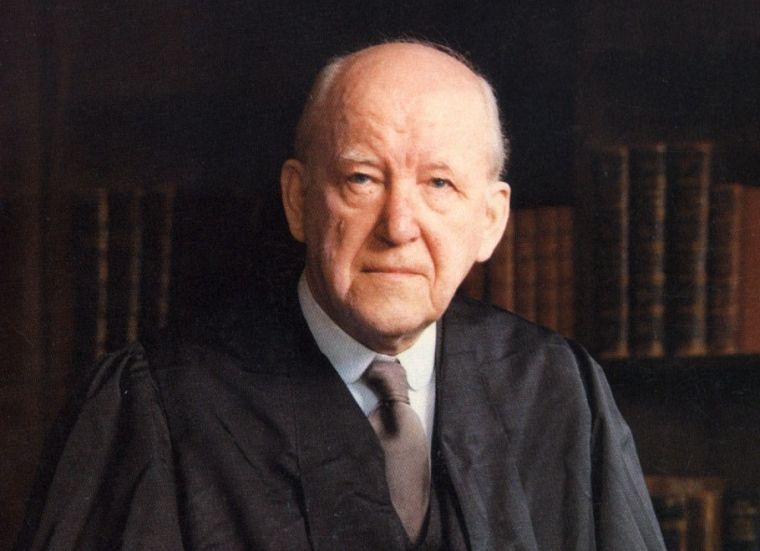

Fifty years on from when Martyn Lloyd-Jones gave his address to the Second National Assembly of Evangelicals, the line drawn on that evening is as clear as ever and the questions have not gone away. How do you define an evangelical? And do evangelicals compromise their convictions when they associate with people who don't share them?

The events at Westminster Central Hall that night could have been predicted. Martyn Lloyd-Jones had long held particular views on ecclesiology. He saw the Church in true Reformed fashion as "a spiritual fellowship of the truly converted", not defined by any particular body, denomination or building. This view provided a dilemma for those evangelicals who were in Churches which included those people, some in positions of leadership, who were not doctrinally orthodox – by his definition – or perhaps not even Christians at all. Among these Churches was the Church of England.

The solution he espoused in his address that night was not new. In a powerfully-worded call he urged evangelicals to leave their "mixed" denominations and form separate, truly evangelical churches. "Evangelicals spend their time criticising their own leaders, but these men are still your leaders....you cannot disassociate yourselves from the Church to which you belong," he told the gathered clergy and church leaders. "That is a contradictory position, and one that the man in the street must find very hard to understand."

Lloyd-Jones, a towering figure in 20th-century evangelicalism, had long held that evangelical Anglicanism was a contradiction in terms. But what he saw as the threat of the ecumenical movement had reached such an extent for Lloyd-Jones he felt the time had come for a separation. Not that he saw it as a schism, because this separation would involve true believers separating from unbelievers: "The only people who could be guilty of the sin of schism were those who in reality belonged to the body of Christ....and yet remained separate from one another in different denominations," he said. "They, and they alone, could be guilty of that sin [schism]."

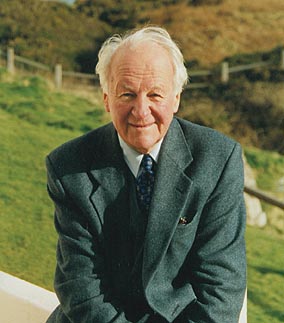

He had been invited to give the address by the Evangelical Alliance, which knew his position. But the chair of that meeting was John Stott – another bastion of the evangelical movement and a self-confessed Anglican evangelical.

In a polarising move Stott stood up and contradicted Lloyd-Jones after he had finished. He argued the Anglican Church was both biblical and evangelical and so evangelicals had a natural home there. "Evangelicals like myself, believe it is the will of God to remain in a Church that is sometimes called a 'mixed denomination'," he said later. "At least until it becomes apostate and ceases to be a Church, we believe it is our duty to remain in it and bear witness to the truth as we have been given to understand it."

John Stevens, national director of the Fellowship of Independent Evangelical Churches (FIEC) unsurprisingly defended Lloyd-Jones in a blog post on Monday. The FIEC's policy on unity is shaped by Lloyd-Jones and Stevens said his "overriding concern was the need to defend the gospel, and never to compromise it for the sake of acceptance or preferment". Although "he got much wrong", Stevens wrote that Lloyd-Jones was "miscast" as a divisive figure.

"It is a wonderfully stirring and compelling call to gospel faithfulness in the face of gospel compromise, and for the need for evangelicals to express visible unity for the sake of gospel clarity in the nation," said Stevens.

He concluded: "We ought at the very least to recognise the vital importance of protecting the truth of the gospel and gospel ministry. In every generation evangelicals will face internal and external dangers to the gospel, which lure us to compromise or relativise the truth. We need to be on our guard against such dangers and reflect carefully on how to address them."

Ian Paul is an Anglican evangelical theologian. He responded to Stevens' post and said it offered a "fascinating perspective" and "deserves reading by any evangelical".

But he said Stevens' comments about evangelical doctrine highlight a "major difficulty with the idea of a 'pure church'".

He told Christian Today: "John defines evangelical belief as centring (at least on part) around 'inerrancy of Scripture, the reality of Hell and penal substitutionary atonement.' Many evangelicals have questioned these doctrines, not on the basis of changing culture or hermeneutical sleight of hand, but by revisiting what Scripture itself says (how many times does Paul mention hell?).

"Many Anglican evangelicals, myself included, would rather define evangelicalism as centred on Scripture – as in fact the Church of England, as a Reformed part of the Catholic church does in its ordinal and formularies, which is why we find a home here – rather than defined by certain specific doctrines, despite the risks inherent in that.

"The basis for unity that John is happy with – based on such 'key doctrines' – actually leads to almost no unity at all with others, so that, as he himself points out, FIEC churches won't even act in partnership with Churches Together, whose agenda now is restricted to shared actions rather than an aspiration for doctrinal or institutional unity.

"It seems to me, then, that Stott was right – and I will happily remain both an Anglican evangelical and an evangelical Anglican."

Fifty years later, it seems the debate rages on.