Friends, not frenemies: towards meaningful dialogue between Christians and Jews

There could hardly be a more timely topic than how we combat the cancer of anti-semitism. The Chief Rabbi's challenge to the Labour Party is still echoing around the country, as – sadly – is the evasive response of the Labour leadership. Jewish children are abused on the London Underground by a man shouting verses from Christian Scripture at them (and are defended by a young Muslim woman, apparently more attuned to the outrage than some Christians would be!).

And the Church of England publishes a report on the record of Christian anti-semitism which has stirred acute controversy and raised the question of what sort of real reparation for centuries of bigotry and violence is really possible and whether all the nettles have actually yet been grasped.

The biggest nettle of all, of course, is the issue raised by the Chief Rabbi in his critical comment on this report. Is it clear that evangelisation is out? No ifs or buts: Jews simply will not sit down and dialogue if there is any perception that there is an agenda of conversion. Rabbi Mirvis does not see any sign that this is promised. And for him and others, this puts the Church of England well behind the Roman Catholic Church whose 1965 teaching document Nostra Aetate declared in unambiguous words that God had not 'rejected or accursed' the Jewish people and that no engagement with them should suggest this.

But apart from this, there are other matters that need to come into play from the Jewish point of view if dialogue is to get off the ground. The Church has to recognise just what Jews believe about God, about the 'peoplehood' of the Jews, about the Land and about the Torah. And once these basic recognitions have been secured, there is the need for acknowledgement of the specific ways in which anti-Jewish violence and discrimination have operated in this country, as a direct result of the legal status of the Church of England.

For the most part, Anglicans from the 17th century onwards did nothing to further the emancipation of Jews. Although this was also true of their attitude to other religious minorities outside the Established Church, it is essential to face the fact that this weighed heavily on a small and vulnerable community. Only one or two voices were raised from the Church in condemnation of the serious anti-semitic riots in British cities in the 1750s. Jews were prohibited from studying at universities, professing the law or entering Parliament. It is an irony that even when the requirement for the Regius Professorships of Hebrew in Oxford and Cambridge that he be an Anglican priest was lifted, the subsequent appointments were still of Christians.

In other words, traditional Christian anti-semitism is not just an aberration of the Middle Ages or of less sophisticated Christian communities; it was enshrined in the story of the Church of England and must be honestly named. But to correct the centuries-long bias in culture and institutions, there surely needs to be a visible commitment to genuine study and dialogue, as well as first-hand learning in the training of Anglican clergy - if only to counter the lazy and pernicious use of clichés about 'law versus gospel' – clichés that are routinely recycled in sermons; or the use of a term like 'pharisaism', without any understanding of the historical context; or ill-informed assertions about the Jewish world of Jesus' day.

Countering the history of hostility, then, doesn't just mean making sure that Anglicans are ready to resist any language that demonises or delegitimises the state of Israel, but making sure that casual and ignorant characterisations of Jewish practice and thought, in history and today, are resisted with equal force. The temptations are always there to treat Judaism as – on the one hand – a thing of the biblical past, now decisively left behind by enlightened Christian truth or – on the other – as a kind of sinister shadow to Christianity.

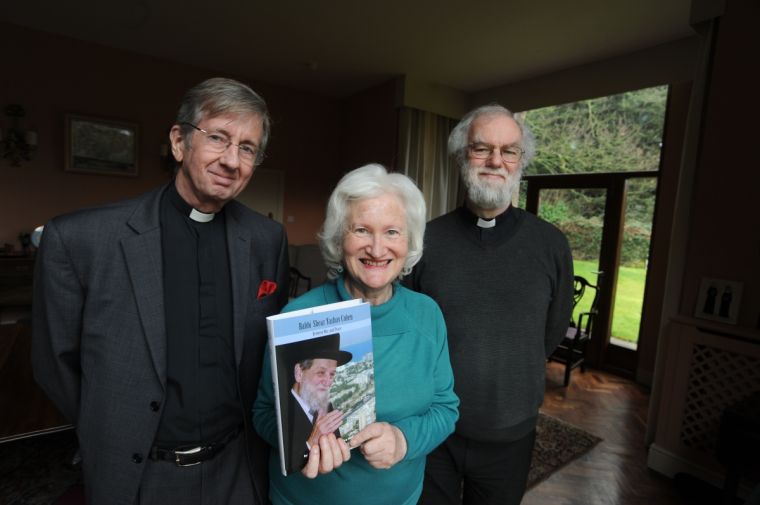

And all this means being crystal clear about what is needed for real dialogue between Christians and Jews in general, and Anglicans and Jews in particular. On the basis of the long (11 years or so) experience of one small but intense and committed local dialogue group in Broughton Park, Salford, Greater Manchester, a few definitions and priorities have come into focus, and these are offered as an example of good practice.

(i) The Jewish concept of God

There seem to be two approaches to the deity in Judaism, which may seem on the surface to be in tension but which manage to be reconciled in the daily life of the Jew. First of all, the Hebrew name of God is not a noun but a verbal form, 'I will be what I will be' (Ex.3.13-14); this is an austere witness to an absolute mystery - a deity who is not an individual person in anything like the normal sense (or in the sense often suggested in popular Christian devotion). But at the same time, there is the God who is a comforting, even intimate presence – the God of other passages in the Torah and in some aspects of Jewish practice across the centuries, especially the Hasidic movements.

The great Jewish philosopher and Talmud commentator, Moses Maimonides (known as Rambam: 1035-1104), stated that we could define God only by what He is not. But on an everyday level, Jews would be lost without constant recourse to God, expressed in the performance of the laws of the Torah in everyday life. What we do – especially what we do in treating other human beings – can bring us closer to God. Trying to change either pole of this tension is to strike at the heart of Jewish identity. Christians who think in terms of a personal relation with God that is not expressed in law and covenant will fail to understand the necessary and creative tension between God as mystery and God as lawgiver that Judaism lives with.

(ii) Jewish peoplehood

This is about how Jews are all connected to each other throughout the world, by way of family, history and shared practice. So the basic Pesach Seder – the Passover meal – is the same in India and Istanbul, in Toronto and Tel Aviv. Some customs differ, but the structure is the same, and this makes each individual Jew think of all the other 14 million with deep love and sympathy. This is especially strong in our own day, given the constant awareness of the 6 million Jews who were slaughtered in the Shoah, and the 7 million who now live in the State of Israel.

At the key festival times of the year – and often just before the beginning of Shabbat, Jews tend to make contact by phone, skype or social media with loved ones, whether in this country, in Israel, or wherever else they may be in the world. They also feel personal pain and shame when a Jew behaves badly or sinfully, and at these tragic times they will pray even more earnestly than usual for forgiveness.

The 10-man minyan that is needed for a full religious service, the week-long minyanim that gather in the home of someone who has recently died – these are marks of the communal spirit of Jewish identity, the determination that no-one be left behind, and they reinforce the sense of being a people.

(iii) The Land

Jews were given the Land of Israel as a holy trust in order that they could carry out to the full this gift of peoplehood and intensify their study of the Torah. As one of the great rabbinic teachers of the recent times, R. Shear Yashuv Cohen (1927-2016), insisted, the single mitzvah (commandment) to settle in the Land is more important than all the other 612 mitzvot together. So many Christian commentators ignore, minimise or misrepresent this. But it is again a key theme. The reality of Israel represents the fact of living Jews choosing their own destiny.

Christians are all too prone to thinking only about dead Jews – the characters of Hebrew Scripture, the 'Old' Testament – or perhaps 'wandering Jews' – powerless exiles, leading a wretched and rootless life. Many forms of anti-semitism, open and concealed, are rooted in an unwillingness to confront Jews as people with dignity and freedom, people who are not imprisoned in the stereotype of Jewish misery that has been created and intensified by Christian propaganda and Christian persecution.

The sacredness of the Land and the commandment to inhabit and cultivate it is not the preserve of any single political agenda – Israel is a country of passionate and open democratic argument about these things; but to attempt any kind of dialogue with Jews without understanding what a Christian might call the 'sacramentality' of the Land is a waste of time.

(iv) Torah

The word means 'teaching' – 'everything you need to know about Judaism': how to deal with other people in a consistent and principled way (law), how to argue, how to read the Bible and the commentaries, how to live in the Land. For the orthodox Jew, Torah encompasses both the text of the Hebrew Bible and the commentaries, and is holy and sacrosanct. But this doesn't mean that it's static. Torah is not a car-owner's manual, but rather a blueprint for development, a source of solace, a cure for the heart and mind, the best kind of therapy that exists.

One major contemporary scholar, Rabbi Dr Nathan Lopes Cardozo, describes Torah as a form of 'rebellion'. It is something that unsettles our comfort zones and overcomes our boredom and apathy; in a memorable phrase, he says that Halacha, the prescription of the law, 'was astir while the world was sleeping' in biblical times.

In order adequately to approach the Torah, a good knowledge of biblical Hebrew and Aramaic is essential; translations won't do. Because Hebrew vocabulary is very small compared to that of English, every 'jot and tittle' of the text is open to interpretation and argument, argument based on sound language skills and knowledge of Jewish norms.

In addition, the Torah is a two-way conversation between God and the Jewish people. Familiarity with the commentaries in the original language is obligatory. You can't interpret the Bible as you please and ignore the bits you don't like; you must immerse yourself in a living tradition of commentary and practice.

This is why it is so wrong when Christians speak in a way that demeans the Torah and the people whose life depends on the Torah. Once again, clichés about 'legalism' or 'rigidity' have to be rooted out, and challenged whenever they occur. It is wrong to take Torah texts out of their setting and ridicule them; this serves only to reinforce the neglect of serious and demanding ethical principles in our society today.

Anything that is to be a constructive dialogue between Jews and Christians will have to factor in these points. And specifically in relation to Anglicans, it is vital that Jewish people are made to feel cherished and protected by the Church of the nation. Those who have historic cultural power are often unaware of the impression of 'effortless superiority' they can convey, and the threatening effect of this.

There needs to be real humility in listening to authentic scholars – and two things that a great many Christians don't realise are that not every rabbi is a scholar, and that Judaism has no distinction between clergy and laity, so that someone a Christian would see as a 'lay' person is just as likely to have scholarly authority. It is certainly also vital that Jewish scholars should be invited to teach in Anglican and other Christian training institutions. We have known of some in years past – but not now – that have organised student exchanges with Jewish institutions, and surely this face-to-face encounter on level ground is of the first importance.

Dialogue is not searching for a new set of religious formulae that we can all sign up to, nor a fight for the victory of one party over another. The beginning of wisdom is to understand honestly what another participant is claiming and why – and not to assume that one's own version of the other's thinking is the last word. Quite a bit of would-be inter-religious dialogue falls at the first post with this. Christians who complain that Sunni Muslims seldom seem to bother to read the gospels and find out what Christians say about themselves might reflect that Jews feel much the same when Christians argue with or criticise them in the light of what Christians think Jews say or mean or do.

And what emerges from authentic dialogue is – at the very least – a new sense of both yourself and your dialogue partner; perhaps a surprise at the degree of convergence, perhaps a surprise at a deeper divergence than you ever imagined. Usually both! Thinking about the four pillars of honest Jewish Christian dialogue listed above, there are certainly instances of wildly variable patterns of convergence and divergence. Early and mediaeval Christian thinkers would have agreed enthusiastically with Maimonides in so many words that you could only say of God what he was not, and that he wasn't a person in any sense resembling a human individual.

The deep and loving interdependence of the connection between separated members of a people is echoed in Christian teaching about our interdependence in the Holy Spirit. Yet Christians have always found it hard to understand the significance of the Land and have frequently misrepresented its meaning for Jews; and – as we have seen – they are prone to misread what Jews think about Torah, simply because the first Christians came to the conclusion that Torah did not have to be observed in all its details by new Christians from gentile backgrounds.

But one thing ought not to be in dispute. For Jews and Christians alike, the very shape of revelation is that the Almighty calls and creates a people, whose loving obedience to him manifests to the world the character of the divine. This people is united in the history of the Exodus and the giving of the Torah. The community living under law, and the shared history of liberation become the active presence of the Almighty in the history of the world. This is sealed by the covenant God makes – makes and continually renews. Nothing in Christian Scripture makes any sense without this background set of assumptions. And even when the new Christian community has emerged as distinctive, there is still a refusal to say that this basic shape of God's action has been breached, that the covenant has been repudiated.

So it should be – as Nostra Aetate says very plainly – impossible for Christians to say that there has been a change in God's purpose, or that the Jews are no longer 'chosen'. The real difficulties arise when Christians try to hold together two apparently incompatible ideas. On the one hand, God does not change His mind; on the other, Jesus is believed to be a point of climax in Israel's history after which a different sort of community becomes possible – one in which the divine call to become a people is somehow extended to the non-Jewish world. When Paul tries to make sense of this in his Letter to the Romans, he clearly finds it difficult, yet he obstinately insists that God has not rejected the Jews. Despite some of the deeply negative language about the Jews and more particularly the ruling elite in Judaea at the time of Jesus, no Christian writer dares to suggest that God has now turned his back on the first promise; and this of course must mean that the Jewish bond with the Land is not just cancelled, even if it is not of any significance for non-Jewish Christians. And if so, it has to be something that Christians are prepared to recognise and discuss openly and imaginatively with Jews who take the promise seriously (it is too easy for Christians to talk only with the sort of Jew who is indifferent to the Land as the site of divine promise).

Some individual converts to Christianity from Judaism across the ages have contributed to mutual understanding; sadly, others have just repudiated their Jewish identity –as if the only legitimate role for the Jew now was to become a Christian. That sounds wrong, even in the terms of Christian Scripture, and it certainly paralyses dialogue. If the Christian believes that every human being will finally 'come home' to a relation with Jesus, that is a belief that must never lead to manipulation, proselytism, the devaluing or delegitimising of Jewish reality and belief here and now. Otherwise, Christians are simply treating their Jewish neighbours as people who ought to become members of the Church but incomprehensibly refuse to do so – which is one of the sources of the worst follies and offences of Christian history, the myth of Jewish 'stubbornness' and 'rebelliousness' which disfigures so much Christian writing from the early Church till relatively recently.

For the Christian, the haunting and hard question is how to speak about the 'uniqueness' Christians ascribe to Jesus without either diminishing his own Jewish identity (indeed, as many scholars would say, his own place within a recognisably Jewish world of charismatic/Pharisaic teachers or healers), or demeaning the primary revelation that is God's gift and call to the children of Israel. Perhaps for the Jew, the equally haunting question in dialogue with Christians might be how to maintain the uniqueness of God's goodness and faithfulness to Israel as a 'light to the nations' without completely dismissing the Christian claim to be in some way part of the same story, but with another focus and another horizon.

Of course, Christians also need to be aware that, while they are obliged to make sense of their Jewish heritage, Jews may not feel the same obligation to make sense of Christianity except as a dangerous mistake, or even betrayal and distortion of their belief. Any Jewish person committing to dialogue will presumably think there is a little more to it than that, and that the task of living constructively alongside those who claim to have at least some language about God in common is not a waste of time. But the Christian should be prepared for the fact that Jews are not under any compulsion to engage – and that the history of Christian abuse and persecution is hardly an encouragement to them to do so. Where true dialogue does happen, the Christian may well feel both humility and a sense of something slightly miraculous.

We started this article by voicing the question of whether there were nettles that had not been grasped in recent discussion. We have written on the assumption that there are difficult conversations that are necessary – but also that these may be enlarging and enriching: a conversion all round to the mystery of the God whose name is a verb, who is known only in action, not as a distant object of speculation. We hope that a Church that is still in so many ways in denial about the level of its misunderstandings may yet wake up and be ready for this enrichment – and that the Jewish sharers in the dialogue may also find new dimensions in the reality of Land and Torah and kinship that defines them as it always has done.

Dr Rowan Williams is Master of Magdalene College Cambridge. Dr Irene Lancaster is Chair of Broughton Park Jewish Christian Dialogue Group in Salford, Greater Manchester.