From Witches To Refugees: Centuries After Salem, We're Still Looking For Someone To Blame

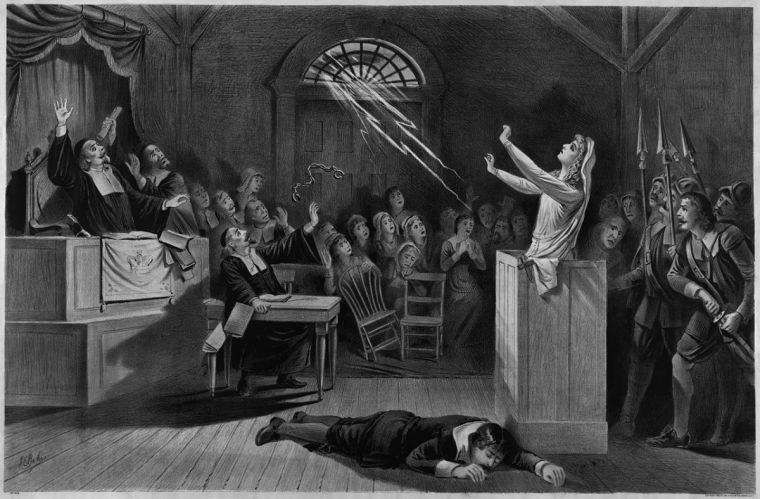

The infamous Salem Witch Trials of Massachusetts began on this day in 1692. Centuries later, they still have much to teach us.

The trials focused on certain women in the community accused of having 'bewitched' other members of the heavily Puritan, Christian community.

By the summer of 1692, the local jail was full of women who had been accused. Supposed victims cited apparitions and convulsions as evidence of the supernatural attacks, claims that would be used against the suspected witches, many of whom would be interrogated, tortured and ultimately executed.

The accused could confess to witchcraft and be outcast – or refuse to confess and be killed. In September that year, 19 of the accused who refused to confess were hanged.

The trials are often held out as a tragic example of how dangerous religion can be. It's often assumed that modern society has progressed far beyond the hysteria of Salem, but a brief glance at Twitter and international politics reminds us that society is always using heightened rhetoric to marginalise and persecute the perceived 'other'. Salem still has much to teach us.

Human history has frequently seen ethnic minorities used as scapegoats to bear the blame for any society's ills. Such an approach has reared its head recently with hysterical politics that provoke alarm by preaching about the invasion of immigrants and the evils of foreign religions.

Travel bans on Muslims, 'extreme vetting', the erection of great dividing walls – these very ideas encourage inherent suspicion of other ethnicities in a society. Division engenders the distance that enables intense suspicion of the other – people always fear what they don't understand. The ultimate tragedy of this is that when the desperate come knocking – when refugees flee for their lives – they pay the price of society's prejudice.

Legitimate fears about security in an age of terror aside, it would be naive to assume that the popularity of populists like Donald Trump or Nigel Farage in Britain has nothing to do with the ability of those leaders to manipulate a fear of outsiders. Such fear may be instinctive, but the Bible teaches that strangers should be welcomed, because we were all strangers once. Jesus preached about love of neighbour, and even more radically, love of enemies. He came to bring humanity together, not tear it apart.

But it would be wrong to compare the inhuman errors of Salem only to right-wing politics and Donald Trump. It is all too easy for liberals to find ways to casually condemn those not part of the 'in-group'. Those who think differently should be 'no-platformed', they do not deserve a voice. Why call someone 'conservative' when you can simply label them a 'bigot' – and ignore them completely? As we now know, social media bubbles actively encourage us to avoid and dismiss those with whom we do not agree.

Passionate disagreement on crucial issues is inescapable, and is often necessary – but it need not turn into a witch-hunt.

The Salem trials are often noted as a grave example of Christian superstition used to justify the oppression of minorities and 'the other'. It is worth noting that many Christians at the time, and since, condemned the trials. In 1697 the Massachusetts legislature made January 15, 1697 a day of public penance and fasting for the sins that had been committed at Salem.

Such repentance can't undo the crimes that were done, but they can mark the moment as one to never be repeated. Not many in America believe in literal witches who've come to destroy their society. Many though still fear what they do not understand, and can use any self-protective ideology to justify their denigration of 'the other'. You don't need religion to be tribal.

Christians should look back on the sins of Salem as a warning. The trials remind the Church to lead with wisdom not fear, and to show kindness and understanding to a world always looking for someone to blame.

You can follow @JosephHartropp on Twitter