George Whitefield: How John Wesley's friend and rival found peace with God

In February 1738 off the coast of Kent and near the port of Deal, two ships were anchored.

On board one of them was a man who would, in a few years, go on to become famous around the United Kingdom.

He would, along with his brother, begin a movement that spread like a bushfire across the country from Cornwall in the west to the north of Scotland.

He name was John Wesley, now returning home after failure and heartache in the recently acquired American colony of Georgia.

As his ship docked on the east coast following the long journey across the Atlantic, John still felt a deep sense of embarrassment.

On board the other ship anchored outside that small port on that winter night in the reign of George II, was a man who had come from much more humble beginnings than the Wesley brothers.

He was heading in the other direction – to Georgia and colonial America.

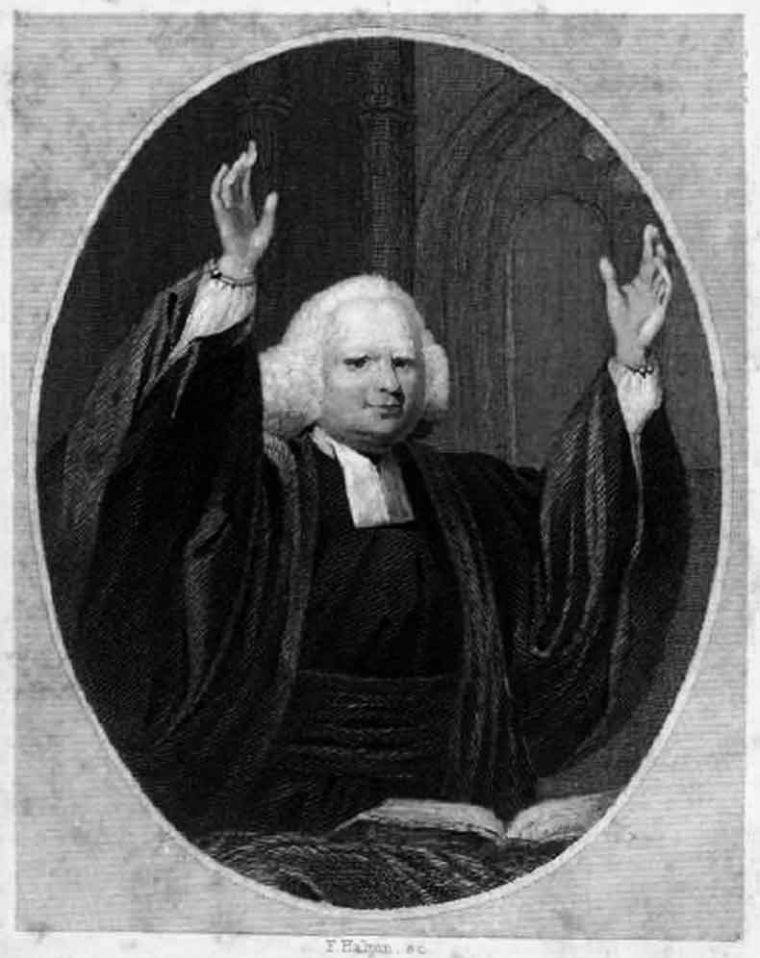

Born in a Gloucester pub, George Whitefield, the pot boy from the West Country, would go on to conquer America with his energy, his preaching, his enthusiasm and his faith in the Christian gospel.

From Georgia and South Carolina in the south to Philadelphia and Boston in the north his voice and personality would become known throughout the American colonies.

The sickly son of the innkeeper would preach to huge crowds across the American colonies and he would become, within a few years, the most famous man in the world.

The two ships lay close to each other, Wesley waiting to disembark and Whitefield, along with his colleague and friend, the London merchant, James Habersham, waiting to set sail as he had been for several weeks.

Wesley did wonder if he should visit his friend, for they had first known each other during their time at Oxford University when Whitefield had joined Wesley's Holy Club.

Wesley cast lots, and decided not to visit but he would, instead, write a letter before disembarking and travelling to London.

His letter was not encouraging, for in it he told Whitefield that he was wasting his time going to Georgia, as he would fail in his mission.

How wrong he was.

At the heart of the city of Gloucester stood the Bell Inn, one of the largest and busiest hotels at that time in Gloucestershire and where George Whitefield was born in December 1714.

The pub itself is no longer there, unwisely knocked down in the 1960's to make way for a row of anonymous shops leading to Bell Inn walk – the only reminder of its existence.

Only a few yards from the site of the old inn in Southgate Street is St Mary de Crypt, one of the oldest churches in the city of Gloucester.

Take a step inside and you'll see a pulpit complete with sounding board above it enabling the preacher's voice to travel further. Whitefield hardly needed one of those even on the one occasion he preached at St Mary's – his first sermon ever.

A few steps from the pulpit you'll find the school room, which dates from Tudor times. It was here that George was educated until he left Gloucester, in 1732, to go to Pembroke College at Oxford University.

Pembroke was one of the smallest and poorest of the colleges and while George may have been a student of sorts he also had to pay his way, which he did, acting as a 'servitor' to the other more wealthy gentlemen students.

A servitor was an undergraduate student who received free accommodation (and some free meals) but was also expected to act as a servant or skivvy to the other students in the college.

It meant undertaking the most menial of tasks including clearing out the bed pans, washing and cleaning the rooms as well as doing the academic work the other students were too lazy to do. It's also clear from his diaries that he was bullied.

While Whitefield must have cut an impoverished figure at Pembroke, his time there also became a time of renewal in his life.

It was at Oxford that he met the man who would be his friend as well as a fierce rival for the next 40 years.

Across the road from the rather small and undistinguished Pembroke College are the rather more elegant and impressive surroundings of Christ Church College. That's where the Wesley brothers lived and studied and where Whitefield first met them.

While George came, as we have seen, from humble beginnings, Wesley's background was rather more impressive through in some ways no less impoverished.

Despite having a rather weak and wayward clergyman father, Wesley had a formidable mother; the remarkable Suzanna Wesley, mother to 19 children, nine of whom had died in infancy.

It's said of Susanna that 'although she never preached a sermon or published book or founded a church she is known as the Mother of Methodism'.

John was hugely influenced by his mother and her own brand of holiness and piety.

With that in mind he formed, in 1729, the Holy Club at Christ Church.

Each day the club members set aside time for praying and examining their spiritual lives, studying the Bible and meeting together.

But they also took food to poor families, visited the local prisons and taught orphans how to read.

They celebrated Holy Communion on a regular basis, something that rarely happened at that time in the Church of England, and they fasted on Wednesday and Friday.

They were a formidable lot, though mocked by the other students who scoffed and called them 'Methodists' as they were so methodical in seeking to serve God.

Growing up in Gloucester, George had been a very normal boy.

Despite his education, first of all at the Cathedral school, then St Mary's, George had played pranks, read books he shouldn't have read, played truant from school and, later in life, claimed that he had stolen money from his mother.

Later on at Oxford, remembering his childhood, Whitefield believed that he wasn't good enough to be of service to God; there were too many things that he had done wrong as a young person.

He also had a deep sense of unworthiness despite a growing belief that he might be called by God to be ordained.

But it was in the Holy Club, probably a diversion from the misery of his life as a servitor, that George Whitefield began a new spiritual journey that changed his life; a very painful spiritual experience and one that almost broke his already weak body.

This inward spiritual battle also brought him to the edge a nervous breakdown, before he later experienced what he would call a new birth.

This experience was to be the hallmark of the evangelical movement he went on to establish, including the early Methodist movement.

At Easter 1735 the storm broke as Whitefield, very much like Wesley three years later, 'felt his heart strangely warmed'.

At that point came a sense of peace, Whitefield returned home to Gloucester renewed in spirit but seeking also to regain his shattered physical health.

Richard Atkins is a Methodist minister and is the Faith and Ethics producer and Sunday Breakfast presenter at BBB Radio Gloucestershire. Follow him on Twitter @atkinsradio

This is the first in a four-part series. Next time – the open fields and the good ship Whittaker.