Good disagreement: Can the CofE hold it together?

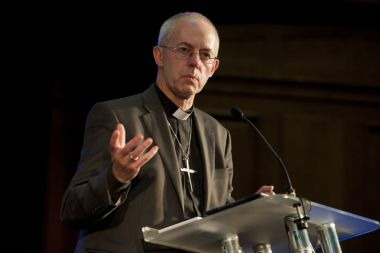

The Church of England has got a lot going for it. The Archbishop of Canterbury is respected and highly capable, it's not doing too badly numerically and it's got a bit of swagger back in its step.

On the other hand, even though the vexed question of the consecration of women as bishops was passed last year and they have been coming thick and fast ever since, no one could say that it is an entirely happy family. The elephant in the nave now is human sexuality, code for "Is it OK to be a gay Anglican?" This is a far more bitter pill for conservatives to swallow than the female bishops one and it could yet make shipwreck of the entire enterprise. It has arguably already done so for the Anglican Communion, of which it is the mother Church. The ties that bind it have never looked so fragile and there is quite a good possibility that a meeting of Primates called to Lambeth in January to resolve the question of how Churches stay Anglican while loathing each other will end in catastrophic failure.

It's against this background that Good Disagreement has been published. Edited by Andrew Atherstone and Andrew Goddard, it is composed of essays by Anglicans attempting to do what the title says. It is introduced by the Archbishop of Canterbury, who has made reconciliation a theme of his time in office so far. He says that "whether the outcome is unanimity or separation, it seems the only way to imitate Christ in our conflicts is to invest trust, love and time in the people from whom we are currently divided".

Anyone turning to it for a quick "how to" theological fix will be disappointed; it doesn't provide a check-list of sound and unsound doctrines. However, it does do an excellent job of addressing the deeper structures of disagreement and reconciliation. It puts disagreement in historical contexts ranging from Martin Luther and the Reformers through Wesley and Whitefield, Dietrich Bonhoeffer and John Stott. It looks at reconciliation in Paul's letters, ecumenism, and the link between unity and holiness. There are chapters reflecting on interfaith dialogue, women in leadership and what happens when churches really do fall out.

One of the most interesting chapters is by Tom Wright. The former Bishop of Durham writes about "pastoral theology for perplexing topics". How do we distinguish between things that matter and things that don't? The Apostle Paul stresses unity, but at the same time he is passionate about holiness. It isn't that anything goes. In fact there are deadly threats and solemn warnings against immorality and the "works of the flesh" (Galatians 5). So how can we tell the difference?

Wright begins with Paul's vision of the Church. It is one great worldwide family, and anything that divides it into ethnic groups – like Jewish ritual practices such as circumcision – can't be allowed to affect that fundamental unity. But sexual behaviour is related to belief in the one Creator God. Honouring God in our bodies is "a Trinitarian ethic flowing directly from the Trinitarian reworking of monotheism itself".

Does this take us very far in thinking through the issues that divide the Anglican Communion? Perhaps not, since it's the outworking of sexual ethics in today's world, with its vastly greater understanding of human sexuality, that's the rock on which the Communion, and perhaps the CofE itself, might yet be split. This might be said of the other chapters too. They are without exception wise, well-informed and constructive, entirely fulfilling their authors' aim of helping people think though the problems of how to reconcile "grace and truth in a divided Church". But it might well be that those who most need to read the book won't do so, or if they do they will assume it is a liberal conspiracy (which is very far from the case).

I asked a Christian sociologist a little while ago whether it might be better for the different factions in the Church of England to go their separate ways, as they seemed to be using up a lot of energy fighting each other when they could be doing more useful things. Yes, she said: groups that had a tight-knit sense of their own identity were often more effective than those which were less focused.

I actually think the CofE would lose a great deal if its extreme wings peeled off to independency or Roman Catholicism. I hope it is able to find ways of disagreeing well, but there is still a mountain to climb.