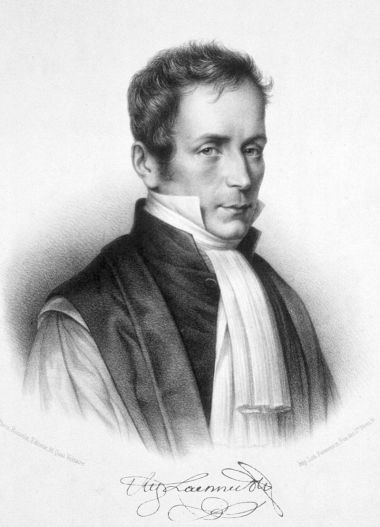

René Laennec: Google Doodle honours Christian medical pioneer

Google's masthead today shows two figures on either side of a pair of lungs. One of them is a modern doctor with a stethoscope and the other is an antique gentleman holding a sort of tube to his ear.

The tube is actually a stethoscope too, and it was the invention of René Laennec, whose 235th birthday it would have been today.

Laennec was a Breton, a brilliant doctor who was also a devout Christian. Born in 1781, he studied medicine under his uncle and treated soldiers wounded in France's revolutionary wars under Napoleon. Before his death at the age of only 45 he made important discoveries about cirrhosis of the liver, melanoma and tuberculosis, the disease that was to kill him.

His most significant contribution to medicine, though, was the invention of the stethoscope. Before this, doctors used to listen directly to patients' chests by placing an ear against the skin ('immediate auscultation'). This was rather awkward in the case of female patients and when patients were obese it was hard to hear the heart in any case.

Laennec recorded his experience of trying to treat a young woman who was rather plump.

"I recalled a well known acoustic phenomenon: if you place your ear against one end of a wood beam the scratch of a pin at the other end is distinctly audible. It occurred to me that this physical property might serve a useful purpose in the case I was dealing with. I then tightly rolled a sheet of paper, one end of which I placed over the precordium (chest) and my ear to the other. I was surprised and elated to be able to hear the beating of her heart with far greater clearness than I ever had with direct application of my ear. I immediately saw that this might become an indispensable method for studying, not only the beating of the heart, but all movements able of producing sound in the chest cavity."

He spent three years testing different materials and making tubes, eventually settling on a hollow tube of wood 3.5cm in diameter and 25cm long. Wooden stethoscopes were used until the second half of the 19th century, when rubber tubing was introduced. The stethoscope made it possible for doctors to listen to what the heart was actually doing and was a huge step forward for medicine.

But Laennec was respected not just for his skill, but for his faith. In the French biography translated by Sir John Forbes, it says he was "a man of the greatest probity, habitually observant of his religious and social duties. He was a sincere Christian, and a good Catholic, adhering to his religion and his church through good report and bad report."

His death was that of a Christian. "Supported by the hope of a better life, prepared by the constant practice of virtue, he saw his end approach with composure and resignation. His religious principles, imbibed with his earliest knowledge, were strengthened by the conviction of his maturer reason. He took no pains to conceal them when they were disadvantageous to his worldly interests; and he made no boast of them, when their avowal might have been a title to favour and advancement."

It's common today for people to set science and faith in opposition to each other, as though they are somehow mutually exclusive. Laennec's life and work show that this is far from the case. He was a man of faith whose early life was spent amid fanatical persecution of the Church, the massacres of priests, the destruction of churches and the confiscation of Church property. Tens of thousands of priests were forced to leave the country and those who refused were executed. But Laennec's faith remained firm.