Has the Church succumbed to half-brained thinking?

Like me you have probably been insulted because of your faith; perhaps someone has even called you a half-wit. But according to a ground-breaking book by Iain McGilchrist, a psychiatrist who now resides on the Isle of Skye, it might be that the whole of Western culture has neglected half of our brains. Let me bring you up to speed with McGilchrist's thesis, and then explore three ways the Church may have succumbed to this half-brained thinking.

McGilchrist argues that the distinctions between the two halves of our brain, though often misunderstood, offer profound insights into why the world is the way it is. In his book The Master and his Emissary, he surveys the medical and psychiatric evidence to present a persuasive case that the fact that our brains have two hemispheres not only shapes how we perceive the world, but is actually a defining factor in our culture.

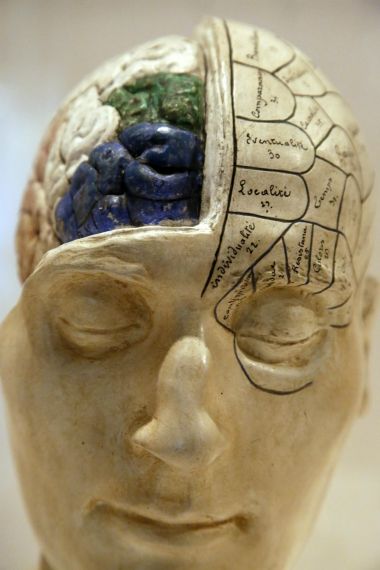

You have probably come across the popular understanding of left-brain vs right-brain. Creative and artistic types sometimes talk about themselves as being "right-brained", whereas logical and analytical types blame the dominance of their "left-brain". This popular way of thinking about the brain arose in the 1960s and 70s after a series of split brain experimental operations. But McGilchrist argues that the experimental data does not support this simplistic division. Instead, he argues that both right- and left-brain function are involved in logic and emotion and both hemispheres are utilised for language and for visual processing. He says that the two halves of our brains present two competing but complementary ways of viewing the world. This split function seen in animals and birds has proved to be very helpful. He states: "a bird for example, needs to focus on a grain of corn that it must eat, in order to pick it out from, say, the pieces of grit on which it lies. At the same time there is a need for open attention, as wide as possible, to guard against a possible predator." Both sharp focus and wide attention are needed for the bird's future existence and the brain divides up the labour between left and right to make sure both are attended to. The left side of the brain prefers to look after focus and the right prefers to look after the big picture; though both are involved in each other's work to some degree.

McGilchrist not only shows how this split between specific focus and wider focus can be applied to human brainwork and experience, but goes a step further to show how the two different modes can be clearly seen in contemporary Western culture. He uses a parable told by Nietzsche to illustrate and summarise his viewpoint. The story goes that there was a wise ruler whose kingdom expanded so rapidly that he had to employ emissaries to visit his dominion instead of going to these regions himself. One of these emissaries, however, grew so confident and assertive that he thought he was wiser than his master, and eventually deposed him. The main thesis of McGilchrist's book is that in the Western world the left-hand side of the brain is the emissary that has usurped the wise leadership of the right, and that this is the reason why we have many problems in our world today.

For an overview of the book you can watch an amazing animation produced by the Royal Society of the Arts:

McGilchrist argues that Western culture has preferenced the left-brain's precision rather than the right-brain's ability to understand context. The world the left hemisphere creates yields clarity on things that are "known, fixed, static, isolated and explicit but ultimately lifeless" while the right hemisphere yields understanding "of individual, changing, evolving, interconnected, implicit, incarnate living beings within the context of the lived world." In the 6th century there was a balancing of the two hemispheres, but since then there has been a drift towards a left-brain conception of the world. This may well be due to the dominance that the left hemisphere has over speech and messaging.

McGilchrist argues that because of left-brain dominance we live in a world of paradoxes: "we pursue happiness and it leads to resentment and unhappiness and an explosion of mental illness. We pursue freedom but we live in a world which is more monitored than CCTV cameras and our daily lives are subjected to what de Tocqueville called 'a network of small complicated rules' that cover the surface of life and strangle freedom. More information, we have it in spades but we get less and less able to use it, to understand it and be wise."

I find McGilchrist's thesis compelling and as I read I find my brain making all sorts of connections with Christian ministry. Trying to readdress the balance, here are the right-brain questions it leaves me with (as opposed to left-brain answers):

1. Has militant atheism flourished in the West because of the monocular vision of left-brain thinking? Have we become used to ignoring the bigger questions of purpose and context that the right-brain would force us to confront, thus reducing the compelling nature of Christianity to our prevailing left-brain culture?

2. Has the Church tried to appeal to left-brain thinking by making the gospel sound more scientific and empirical? The "Four Spiritual Laws" or "Four Points" is a highly popular gospel presentation which seeks to provide the bare essentials of the gospel using scientific or left-brain terminology. But what has been lost in this reduction? Have we tried to neatly package the gospel rather than leave room for mystery and paradox, awe and wonder?

3. Has the Church allowed left-brain thinking to control her strategy by allowing numbers and the measurable to dominate? Ask a church pastor what their plans are for their church and by and large they involve increased attendance or bigger budgets. As McGilchrist observes, in a left-brain world "Numbers... would come to replace the response to individuals." Have we used a predominantly quantitative analysis of our ministry rather than qualitative concepts? Is our success as churches about the number of people that attend or the degree to which we have formed people in the likeness of Christ?

Also does jet-lag affect left-right-brain function? I'm looking forward to exploring more of the implications of McGilChrist's book when I am part of a panel discussion with him at an event hosted by Regent College in Vancouver at 8pm UK time on Wednesday 10th of February. I am expecting my brain to be a little fried as I am travelling out to Thailand for a conference and it is going to be 3am local time on Thursday morning when I join the call. But if you are awake and wish to be part of the online conversation, you can join in here for free.