How can we make peace with the past?

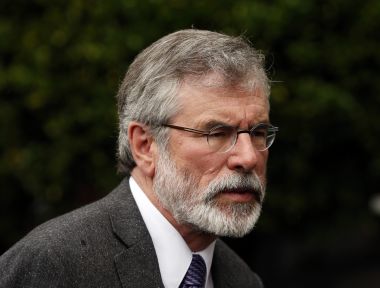

"The poison from the past keeps dripping into the present," said Channel Four correspondent Andy Davies. He was reporting on the arrest of Sinn Fein President Gerry Adams who was questioned earlier this year over the kidnap and murder of Belfast woman Jean McConville.

The death of Mrs McConville in 1972 is one of the most notorious crimes of "The Troubles" in Northern Ireland. Her body was found in 2002 but her killers have never been brought to justice. This year has seen a flurry of police activity and several arrests with Adams being the most high-profile.

He has repeatedly and categorically denied involvement in Mrs McConville's murder or the killings of the 'Disappeared' – men and women in Northern Ireland suspected of being informers of the British who were taken from the streets, questioned, shot and buried.

Last night it was confirmed that human remains found last October were another of the 'Disappeared' Brendan Megraw. He was 23 when he was abducted from Twinbrook in Belfast in 1978. He had recently married and was awaiting the birth of his daughter.

Yesterday evening Brendan Megraw's brother, Kieran, read a statement, "He has been alone for nearly 40 years and now we can bring him home and lay him to rest with our mum and dad," he said, adding, "We hope and pray that the suffering of those still waiting for the return of their loved ones will soon be brought to an end."

A peace of sorts, then, for that family.

But the 'poison of the past' that Andy Davies referred to can be found seeping into many current news stories. For some it brings justice – take the inquiries into so-called 'historic' child sex abuse. Perpetrators are finally being investigated and, in some cases, convicted decades after the original crime. But prosecutions also come with great cost and pain for the victims and survivors.

The past certainly caught up with Susan and Christopher Edwards of Dagenham, East London. They murdered her parents Patricia and William Wycherley in 1998 and buried them in their back garden. The Edwards carried on leading a seemingly normal life for 15 years until they eventually confessed. They were jailed for life earlier this year.

Most of us won't be living with a huge crime concealed in our past. But many of us will harbour unresolved pain; crimes committed against us or by us, large or small but distressing nonetheless.

That's why the term 'historic abuse' is offensive to many survivors, their past is very present and something they have to live with each and every day.

Some of us are tormented by grief for a relative or friend; some are missing from our lives through death, abandonment or family rift.

Popular cultural wisdom doesn't like the past. We should definitely leave it behind.

A quick Twitter trawl reveals the following nuggets: I'm determined to rise above all past mistakes and live a meaningful purpose filled life.

Stop fixating on your past. Live every moment. Live your dream.

Can we really just decide to move on? I'm not sure it's that simple.

The Bible has much to say on the subject. Paul in the New Testament says he is "forgetting what lies behind and straining forward to what lies ahead". In his second letter to the Corinthians he writes, "Therefore, if anyone is in Christ, he is a new creation. The old has passed away; behold, the new has come."

The Old Testament Prophet Isaiah says, "Remember not the former things, nor consider the things of old. Behold, I am doing a new thing; now it springs forth, do you not perceive it? I will make a way in the wilderness and rivers in the desert."

These are powerful words. But sometimes it takes time for us to actually take on board these amazing truths and the process of dealing with the 'poison from our pasts' can be messy.

A quick prayer and a platitude may not be enough. Healing and restoration can come but it may take time and in some cases expert counselling. The Mind and Soul website provides great resources for churches and individuals in this area.

'Freedom in Christ' is a phrase that is often bandied around by Christians. But what does it actually mean? And are we as a church really doing enough to help people make peace with their pasts?

Sarah Lothian is a freelance journalist.