How to read the Book of Revelation

Yet another 'prophecy' about the end of the world comes and goes – but we know, like the proverbial bus, another one will be along soon. One of the reasons for this predictable yet disappointing procession is that we don't really know how to read the Book of Revelation properly – the source of many of these failed forecasts.

Many people leave this last book of the Bible firmly closed, and in some ways I don't blame them. If you do open it, it looks like a very strange text indeed, for at least two reasons. The first is that we haven't read anything else quite like it, and we usually learn how to read things by drawing on our past experience. The second is that, if we ask for help from other people, they will give us a very wide range of possible views, most of which are completely contradictory. So what should we do?

There are actually some relatively straightforward things to bear in mind as we read – though perhaps the most important thing is just that: to engage our minds. God invites us to love him with our mind, as well as our heart, soul and strength (Luke 10:27), and the best thing we can do with Revelation is to keep our hearts and our minds connected with one another. The vast majority of wacky ideas that have sprung from this book can easily be dismissed if we simply ask 'Is this really plausible?'

Here are seven things to think about which will make all the difference:

1. Notice where this book is

Pause for a minute; look at your Bible. Where is Revelation – is it inside or outside the covers? Why is it inside – why did it become part of what is now our Scripture? The first followers of Jesus already had their own Bible, what we now call our Old Testament, and it is worth considering why they felt the need to add anything more. The books of the Old Testament were testimony to God's words and actions in rescuing his people, being present with them, and making his glory known to the world. And so, when God came once more to speak, act and save in the person of Jesus, they needed to include testimony to this as well. Hebrews 1:1-2 puts it very clearly: 'It the past God spoke...but now he has spoken by his Son...' The other documents in the NT testify to what God has done in Jesus, and how we should live in the light of this – so Revelation must be doing the same. If, instead, it set out a completely separate end-times scheme that wouldn't be relevant for another 2,000 years, it would never have been included.

2. Notice to whom this book is written

What kind of text is Revelation? We are given some important clues early on, when the writer says 'John, To the seven churches in the province of Asia: Grace and peace to you...' (Revelation 1:5). You might recognise this phrase, since it comes at the beginning of all of Paul's letters – it is the standard way people wrote letters in the first century. Whatever else Revelation is, it is a letter, written to particular people living at a particular time in a particular place. So although it is written for us as Scripture, it is not written to us. We therefore need to consider how John's first audience would have understood it if we want to know how God wants to speak to us through it.

And of course it means you can visit these places today. You can see the acropolis (upper fortified town) where 'Satan's throne is' (2:13); you can visit the city that needed to 'Wake up!' (3:2) when it was besieged; you can even see the furred-up pipes that carried 'lukewarm' water (3:16) to Laodicea. Cold water is good for refreshing; hot water is good for healing; but lukewarm water is good for nothing! The Laodiceans' problem was not lukewarm faith, but lukewarm 'works' (3:15).

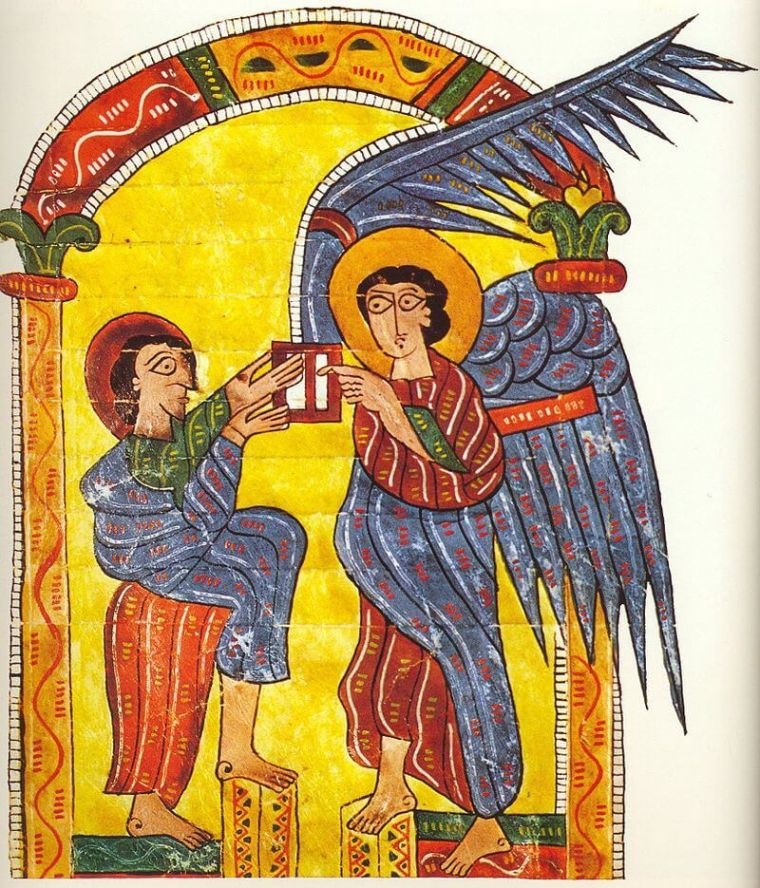

3. Notice the use it makes of the OT

I once spent a week of my life counting the allusions to or echoes of the Old Testament in Revelation's 405 verses. By the end of Friday afternoon I had reached 676 – which is a lot of allusions! It means we cannot really move without bumping in an OT reference. (If you don't believe me, just compare Revelation 1:12-17 with Daniel 10:5-12). When Revelation's first hearers (1:3) come across thunder and lightning (4:5), trumpets (8:7) and locusts (9:3), they are much more likely to think of Mt Sinai (Exodus 19:16), the call to temple worship (Leviticus 23:24), and judgement and restoration (Joel 2:25) than they are to imagine either twee Christian art or armoured attack helicopters (yes, that is one interpretation of Revelation 9:3!).

4. Notice the ideas that it borrows

If I started explaining what Jesus had done like this 'There was a girl who had a red cloak with a hood, and one day she set off into the woods...' and managed to weave in the gospel, you'd know what I was talking about. Or if I started off 'There was once a house with three bears, daddy bear, mummy bear and baby bear...' and ended with Jesus' death and resurrection, you'd recognise it. In the same way, when anyone in the first century read or heard Revelation 12, they would immediately recognise it as the Python/Leto myth. (You can read it here at myth 140.) The great dragon tries to kill the offspring of Leto, but she is rescued, gives birth to Apollo and Artemis, and Apollo returns to slay the dragon. The story was used by Roman emperors to depict themselves as Apollo, the defeater of the forces of chaos and the bringer of peace. Revelation 12 turns it around: the emperor is the bringer of chaos, and only Jesus is the one who brings victory and peace.

This is not an exercise in being 'academic' in our reading. It is just the normal discipline of recognising that the Bible was speaking in the language of its context and culture, and this decisively shapes its meaning.

5. Notice the way it uses numbers

End-times fanatics love to make use of number – and Revelation gives some warrant for this. But it makes use of numbers in a particular way. First, it includes significant words with special regularity – so 'Jesus', the faithful witness, occurs 14 (= 2 x 7), which is the number of perfect witness (since you need two witnesses Deuteronomy 17:6, and 7 is the number of completeness). It also uses 'triangular' numbers (think of the 15 red balls on a snooker table) such as 666. But it is not alone in this in the NT. The 153 fish (John 21:11) and the 276 people on Paul's boat (Acts 27:37) are also such special numbers!

Finally, Revelation uses a common form of numerology in the first century (known as isopsephia in Greek or gematria in Hebrew) in which you add up the numerical value of the letters of a word to give the word's value. This is possible since, before the Arabic number system we use today, all letters had a value and were used in everyday arithmetic. In this way, the number of 'the beast' is the same as a the number of a man's name (in this case Nero Caesar) since both add up to 666. This 'solution' to the puzzle of Revelation 13:18 has been known in academic circles since the 1840s, but sadly has still not filtered down into popular reading. And that leads me to my final point...

6. Notice that it is given to God's people as a whole, not to us each as individuals...

The opening of Revelation invites a blessing on the one (singular) who reads and those who hear (plural, Revelation 1:3). The situation envisaged is not an individual, with his or her own text, reading alone, but a lector at the front of the congregation reading aloud so that others can listen. (This is really the only possible social context of the church's reception of the early Christian writings.) What is true for Revelation is true for all of the New Testament: it was in the first place given to the whole people of God for the building up of the whole people of God.

That means we need to help one another to read and understand aright. Some of the things I have mentioned above might seem just a little technical and remote from everyday devotion. But it is now very easy to access this kind of information. You might want to start with my Grove booklet available post free here. Or you could turn to Craig Koester's Revelation and the End of All Things, or Michael Gorman's Reading Revelation Responsibly.

7. ...and for a particular purpose

But the reason for thinking about these things is not so that we can impress others with our knowledge – it is in order that Revelation can do the work in and among us that it is designed to do. John, our 'brother in kingdom, tribulation and patient endurance' (Revelation 1:9) wants us to understand how we can live as faithful witnesses, testifying to the victory that Jesus has won, in a world which is frequently hostile to God and his people.

In our post-Christendom world, it is a message we badly need to hear – without being sidelined by the latest silly scheme that has been dreamed up in ignorance.

Rev Dr Ian Paul is Honorary Assistant Professor at the University of Nottingham, and is currently writing the new Tyndale Commentary on the Book of Revelation. He blogs at www.psephizo.com