JS Bach: Was the composer of the world's greatest Christian music a believer?

Some years ago I was lucky enough to have a conversation with the late, great composer Sir Peter Maxwell Davies about religious music. We talked about whether the composer of sacred music had to be a believer. He thought not. 'I admire the church as work of art,' he said, 'but I find it impossible to believe.'

There are some important ideas contained within Max's typically honest and clear statement. First, I don't believe for a moment that he was seeking to downgrade religious music by describing it as a work of art – rather the opposite. For a composer of his integrity, there could be no higher evaluation of its worth. Second, and perhaps most important of all, is the evidence of his work. Whether or not he found it possible or necessary to believe, the fact is that he did find it necessary to continually revisit the texts and the preoccupations of the Christian church for his own art. Music takes an honoured place in that tradition. The answer to my question is in the music.

How do we address the same question to composers we cannot talk to? How did faith affect the work of Johann Sebastian Bach?

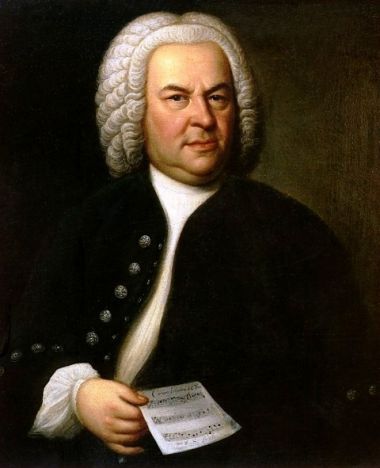

It is a question I wrestled with during the fascinating and immensely rewarding process of writing the volume on Bach for the series A Very Brief History, published by SPCK. Like so many other questions about Bach, a definitive answer remains tantalisingly out of reach. There is little in the way of personal insight in the surviving documentary record, of his personality, his relationships, his feelings, his motivation. There is masses of evidence about his working life, much of it recording his often prickly dealings with employers and colleagues. But not much about the man: as far as evidence of his own religious faith is concerned, we have to content ourselves with some careful but not always hugely revealing handwritten annotations in his own copy of Abraham Calov's translation of the Bible, and the fact that he owned a fairly substantial library of theological works, including two complete sets of the writings of Luther.

Of course, the surviving letters contain plenty of greetings and invocations in the name of God, as would those of any educated person of his background. He casts his cares in the lap of the Almighty when his family gives him trouble, as for example when his errant son Johann Gottfried Bernhard, the only one of his 20 children to grow up to lead a slightly wayward life, got into debt and disappeared. But there is nothing, for example, to reveal his thoughts on the many sad occasions when his children died in early infancy – 10 in all.

To what extent, then, are these scraps of evidence simply the conventional verbal gestures of an 18th-century musician? Or are they evidence of something deeper and more genuine?

One piece of evidence remains: the music.

Even here there is room for conjecture. Like all composers, Bach's output was inextricably linked to the worldly circumstances of his employment. He wrote church cantatas during his period of employment at Weimar, where he was responsible for the music in the soaring, galleried Himmelsburg chapel, and in his last and longest place of work, Leipzig, where his employer the Thomasschule provided music for the weekly sung service and many others besides. He chose the texts, but was answerable to his bosses for those choices.

Leipzig also saw the composition and performance of the Passion settings, the Lutheran Masses, the funeral motets and much else. On the other hand, when he worked at the small but musically congenial court of Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen, he wrote no church music at all because the court was Calvinist and thus had no use for choirs or concerted sacred music. To a large extent, he wrote church music because he was paid to.

In addition, in his last works he did not, as some composers did, dive ever deeper into the liturgy and sacred texts. Instead he burrowed into the technical side of his musical inheritance in an awesome series of beautiful, abstract works of pure counterpoint – the Art of Fugue, the Musical Offering, the Goldberg Variations.

But this only tells part of the story. Towards the end of his life he devoted huge efforts to assembling a work which no church or court could have used as part of the liturgy, the monumental setting known to posterity as the B Minor Mass. Bach didn't call it that – he carefully issued it in separate sections, each under its own title, not as a complete orchestral Mass. Why? What motivated him to rework and newly compose so much elaborate music for a piece which he could never, and did never, hear?

Surely part of the answer has to lie in the repeated exclamations of 'Credo' in the movement he ambiguously titled Symbolum Nicenum: 'I believe'. Most unusually for a German Lutheran work, these words are sung first to a snatch of plainsong, the sort of thing Catholic composers did. Is there a gesture towards ecumenism and the universality of faith here, or even something more?

In the end, I believe Bach was more the learned musician than the musical theologian. But it was in the nature of the Lutheran tradition in which he was brought up and worked to place the figure of Christ front and centre.

When you hear a soloist deliver Bach's searing, personal response to the words 'Mein Jesus ist tot' ('My Jesus is dead') in the St John Passion, there can be no doubt that here is a composer for whom individual faith was important and real.

Andrew Gant is the author of 'Bach: A Very Brief History', published by SPCK.