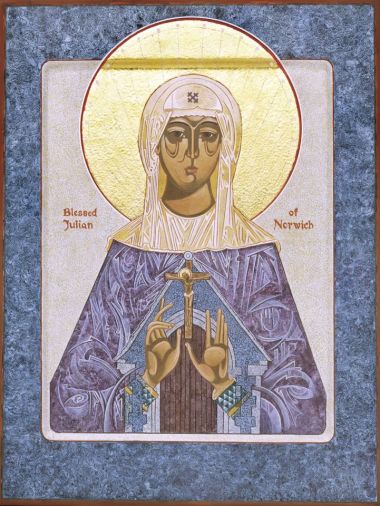

Julian of Norwich: How an unknown hermit produced one of the Church's greatest spiritual treasures

Julian of Norwich was obscure in her lifetime and almost forgotten after her death. She was a mediaeval "anchoress" or hermit who lived from 1342 to around 1416, and Julian wasn't even her real name: her cell was attached to St Julian's Church.

But centuries after she died her Revelations of Divine Love were rediscovered by Christians who recognised in her writing a profound knowledge of God and a spiritual treasure.

It's on this day, May 13, when she was about 30 years old, that Julian recovered from a serious illness that had left her near death. A priest brought her a crucifix and said the last rites of the Church over her. During her sickness she experienced 16 visions of God or "showings" that she recorded not long after her recovery. She later expanded this account into a much longer text.

Julian was the first woman to have a book published in English. But her work was not widely known until it was re-issued in modernised language in 1901, after which it became very popular. She's now recognised as one of England's most important mystical writers.

One characteristic of her work is how she refers to Jesus as the mother of Christians. Divine love is like motherly love, she says. The bond between Christians and God is like the bond between a mother and her child.

Her most memorable image is a very homely one, but very profound. In her original Middle English, it reads: "And in þis he shewed me a lytil thyng þe quantite of a hasyl nott. lyeng in þe pawme of my hand as it had semed. and it was as rownde as eny ball..."

In modern English the passage reads: "And in this he showed me a little thing, the quantity of a hazelnut, lying in the palm of my hand, it seemed, and it was as round as any ball. I looked thereupon with the eye of my understanding, and I thought, 'What may this be?' And it was answered generally thus: 'It is all that is made.'

"I wondered how it could last, for I thought it might suddenly fall to nothing for little cause. And I was answered in my understanding: 'It lasts and ever shall, for God loves it; and so everything has its beginning by the love of God.' In this little thing I saw three properties; the first is that God made it; the second is that God loves it; and the third is that God keeps it."

This emphasis on the enduring and sustaining love of God for everything He has made is a constant theme of her writing.

She says: "God loved us before he made us; and his love has never diminished and never shall."

She also says: "We need to fall, and we need to be aware of it; for if we did not fall, we should not know how weak and wretched we are of ourselves, nor should we know our Maker's marvellous love so fully."

And famously, she says: "All shall be well, and all shall be well and all manner of thing shall be well."

Julian lived at a terrible time in England's history, when the country was ravaged by the Black Death that killed a third of the population. But she maintained a deep faith in God, sustained by an awareness of his love.

There is now a Julian Centre next to the church in Norwich where she lived, devoted to prayer and the study of her work.