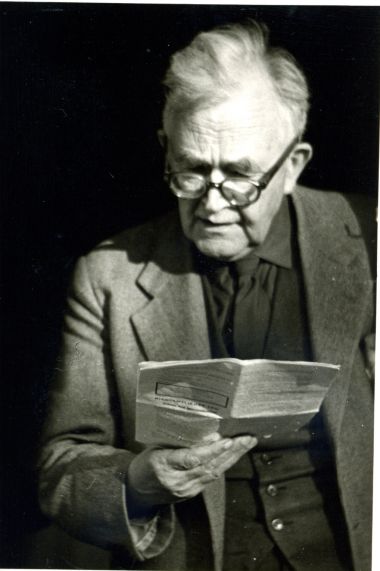

Karl Barth: 10 things you didn't know about a great 20th century thinker

Swiss theologian Karl Barth (1886-1968) was one of the most important figures in 20th century theology. He reacted against the prevailing liberalism of the 19th century and became a leader in the Confessing Church that resisted Nazism. He wrote about the sovereignty of God, election, sinfulness and Christology.

1. He was a pastor as well as a scholar

Barth's works include his famous commentary, The Epistle to the Romans, and his 13-volume work Church Dogmatics, one of the longest theological books ever written. But he began his ministry as pastor of a small church in Safenwil, and while he was formidably learned, he wanted to speak to the Church rather than just to academic theologians, so much of his work is quite accessible.

2. He was a scourge of liberalism

Liberal theology in the 19th century had treated the Bible and traditional Christian doctrine as a human creation that could be reshaped in the light of philosophical and scientific advances. Barth realised how badly this approach had gone wrong when his theological teachers supported German war aims in 1914.

3. He believed God reveals himself, he is not discovered

One of his recurring themes was that God had revealed himself in Christ and through scripture; the initiative was all his. The problem was that while liberals could talk about religion, history and art, they had nothing authoritative to say about God. For Barth, God had revealed himself in Christ and through Scripture. Liberals just talked about humanity and called it God.

4. He didn't believe in inerrancy

On the other hand, not being a conservative evangelical didn't make him a liberal. He didn't believe in the inerrancy of Scripture; he thought that regarding Bible as inerrant was using a foundation other than Christ, which was idolatrous. But he believed the Bible was fundamentally about God, who was "Wholly Other". He has been described as "neo-orthodox", though he rejected the term.

5. Students went to hear him even when they didn't have to

At the University of Bonn his lectures were so popular that around 400 students attended, packing out the largest lecture hall. His seminars were so popular that he had to limit numbers; students had to sit an exam in order to be admitted.

6. He was a leader in the anti-Nazi movement

Barth was the main author of the Barmen Declaration in 1934. It was a fierce denunciation of Christians who aligned themselves with the Nazis and accepted the submission of the Church to the state. It said among other things: "We reject the false doctrine, as though the Church in human arrogance could place the Word and work of the Lord in the service of any arbitrarily chosen desires, purposes, and plans." Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who was to be martyred in 1945, was a signatory. Barth had to resign from his post at the University of Bonn in 1935 for refusing to swear an oath of allegiance to Hitler and spent the war in Switzerland.

7. He believed all politics were under God's judgment

Barth was adamant that the Church had to critique all politics. In the Darmstadt Declaration in 1947 he said that it was the German Church's willingness to side with anti-socialist, conservative forces that had led to its support for Nazism. Western critics took this, wrongly, as support for communism.

8. He had an unconventional family life

Much of his work was undertaken with the help of Charlotte von Kirschbaum, his secretary and theological assistant. She subordinated her own career to his and did not receive the recognition she deserved. Their closeness led to considerable tensions within his immediate and wider family.

9. His longest work might have been even longer

Church Dogmatics, Barth's greatest work, encompasses four major doctrines: Revelation, God, Creation, and Atonement or Reconciliation. He originally planned to write about redemption and eschatology, too, but seems to have run out of steam.

10. His faith was surprisingly straightforward

Barth was asked after a lecture in Chicago if he could sum up his theology in one sentence. He replied in the words of a song his mother had taught him: "Jesus loves me, this I know, for the Bible tells me so." The story has been doubted, but appears to be true.

Follow Mark Woods on Twitter: @RevMarkWoods