No punishment, no repentance: The persecution of Christians in Egypt

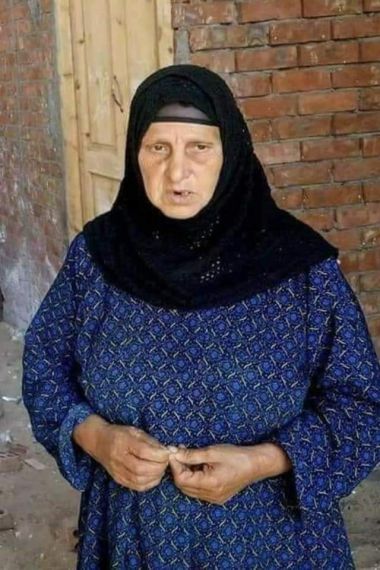

Memories of the attack have never faded from Souad Thabet's mind.

An Egyptian Coptic Christian woman in her 70s, Souad wishes she could forget the moment that a group of Muslim men invaded her home in El-Karam village in Egypt. They dragged her out of the house and stripped her. In her ears, is the noise and giggle of the large crowd of spectators. She was mocked and beaten. Her husband was too.

That was in 2016. Recently, Souad learned that her attackers have been acquitted.

El-Karam is a village of 40,000 people, 5 per cent Coptic Christian. A rumour spread in the village that Souad's son Ashraf was having an affair with a married Muslim woman. Both Ashraf and the woman, Nagwa, denied the allegation. Ashraf believed the rumour to have been spread by Nagwa's husband, who used to be his business partner, but they had fallen out. Ashraf even received death threats and reported them to the police. However, authorities did nothing, and he finally fled the village with his wife and children. His parents remained behind.

One night, a mob of local Muslims armed with weapons broke into several Christian homes, including Ashraf's. After looting the properties, they set fire to them. Ashraf's mother was dragged outside and stripped by Nagwa's husband, his father and brother, as she later testified.

Reconciliation without repentance

Violent mob attacks on Christians in Egypt mostly occur within mixed Muslim/Christian communities, with Christians generally the much smaller population. Radicalised Muslims, and sometimes the local Imams, promote the shunning of Christians, creating a fertile ground for aggression. Rumours of alleged blasphemy, the opening of a new church or even a small conflict over a trivial matter can trigger organised attacks on local Christians.

Often, these attacks are followed by so-called 'reconciliation sessions' meant to resolve the conflict. Christians usually have no choice but to participate. Next, they are pressured, with threats and intimidation, to accept the terms imposed on them: to change their testimonies against the perpetrators or recant their complaints to the authorities. This practice perpetrates a climate of impunity where Muslims who have committed crimes against Christians are cleared of charges or not prosecuted at all.

After one such reconciliation session, the Coptic Christians of El-Karam, whose houses were burned on the night Souad was humiliated and beaten, changed their testimonies against Muslims who they had claimed were the perpetrators. They now said they had been mistaken in the identities of those people due to the dark night. This undermined Souad's case: the three people who had attacked her and been sentenced to 10 years' imprisonment were acquitted last December, as were all of the other Muslims.

"This is a great injustice," Souad's son, Ayad Daniel Attia, told a local expert. "We were pressured many times before to reconcile with my mother's attackers. We refused to do so hoping that we could seek justice by law. The law, however, did not bring us justice, nor did it protect our rights."

Hostile climate

Egyptian Christians have had to fight for their rights for several centuries now. Today, they make up 15 per cent of Egypt's 103 million population. They are hardly newcomers to the land; the Coptic Orthodox Church names the apostle Mark as the founder of Christianity in Egypt.

After Arab armies invaded Egypt between 639-646 AD, periods of severe persecution began under Islam and the church struggled to survive. The number of Coptic Christians dwindled and by the 10th century they comprised only half of the population.

Today, oppression of Christians operates in different ways in Egypt. There is a widespread view in Egyptian society whereby Christians are regarded as second-class citizens. This view fuels their discrimination and creates an environment in which the state is reluctant to enforce the fundamental rights of Christians – despite claiming otherwise. It leaves Christians vulnerable to all kinds of attacks and pressure.

Upper Egypt, in the south of the country, is particularly dangerous for Christians. Islam has been more radicalised there than in the north. Most incidents and mob attacks take place in this region. However, Christians in the poor rural areas in the north experience a similar degree of oppression from radicalised Muslims – especially in the Nile delta villages and towns.

Due to the hostile climate especially in rural areas, neither church leaders nor ordinary Christians can protest these practices. This environment nurtures disregard for the law and contributes to a culture of impunity.

"Dirty Christian, die!"

One of the forms of impunity granted to Islamist radicals is by attributing mental illness to a perpetrator, thus clearing their criminal charges.

Sara* was walking on the street in a busy shopping area in Warraq district of Giza governorate in January last year.

Suddenly, she felt a sharp object hitting her body. "Dirty Christian, die!" she heard a man shout while her legs started to tremble. The man had stabbed her in the neck.

"I didn't feel pain at first," Sara told the local expert. "I must have been in shock. I felt a lot of blood was coming out of my body and I just started dabbing it with my scarf, but it was too much."

While Sara fainted, the attacker, dressed in the typical white clothes of Islamic extremist Salafists, continued to threaten her. While a crowd of eyewitnesses gathered around them, the man did not feel the urge to flee, seemingly confident that his actions would have no consequences for him.

Sara had large, deep cuts around her neck and her life was saved in the hospital. However, the person who committed the atrocious crime was never held to account, allegedly due to mental illness.

Under the rug

This climate of impunity is also created by the police, who often protect and cover up radical Muslims.

There have been numerous reports of murders of Christians who have been asked to renounce their faith and were instantly killed upon refusal. According to an Open Doors' contact, although the names of the suspects are known in most cases, the police frequently display a good deal of inertia in making swift arrests and starting investigations. This sense of impunity acts as a driver of further intolerance and persecution.

Sometimes police officers are themselves the perpetrators: Open Doors recently received new reports of brutal murders of two Coptic Christians at the hands of local police.

Dr David Landrum, Director of Advocacy at Open Doors UK and Ireland, said: "Christians have lived in Egypt for nearly two thousand years. Egypt is their home. It is completely unacceptable that the law does not protect their fundamental human right to practice their faith safely.

"It is completely unacceptable that they can be persecuted with impunity. Unless this culture of injustice is addressed in Egypt, we can expect to receive more reports of oppression and violence. The Egyptian authorities need to act now."

Egypt is number 16 on the Open Doors' World Watch List, a ranking of 50 countries where it is most difficult to be a Christian.

*name changed for security reasons.

Zara Sarvarian works for Open Doors UK & Ireland, which is part of Open Doors International, a global NGO network which has supported and strengthened persecuted Christians for over 60 years and works in over 60 countries. In 2020, it raised £42 million to provide practical support to persecuted Christians such as food, medicines, trauma care, legal assistance, safe houses and schools, as well as spiritual support through Christian literature, training and resources. Open Doors UK & Ireland raised about £16 million.