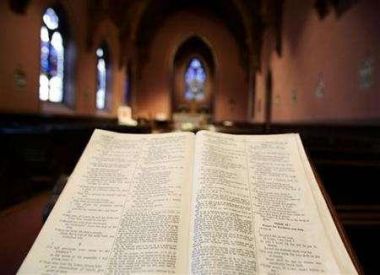

Reading the Bible aloud: Why it's part of worship and how we can do it better

Protestants are people of the book, and evangelical protestants doubly so. We believe the Bible and we want to hear it preached.

We aren't so keen, though, to hear it read.

In most UK churches, attendance at one service on Sunday is the norm. During that service, perhaps 15 or 20 Bible verses might be read – perhaps more if there's a Psalm or a Scripture call to worship. There are around 31,100 verses in the Bible, which means that at a generous 30 verses a week – and ignoring the repeats of the pastor's favourites – the congregation will hear a maximum of 1,560 verses, or a fairly miserable five per cent.

It's worth comparing that to the 1662 Book of Common Prayer. If a congregation followed that through at morning and evening services, during the course of a year they'd read the whole Old Testament once, the New Testament twice and the Psalms 12 times.

This means that in many evangelical churches there are whole chunks of scripture that just aren't read at all.

But alongside this – and perhaps feeding in to the wider problem – there's the question of how the Scriptures are read.

In the heirarchy of participation in worship, where preaching and leading musical worship jostle for position at the top, Bible reading is assumed to be a lower-level activity. Almost everyone can read nowadays, so it's assumed that almost everyone can read the Bible aloud.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

Reading the Bible is a gift and a privilege. But just as a musician practises her instrument, Bible readers need to improve their skills too.

We've all heard passages read in a monotonous mumble, in which nothing of the real story comes out. We've all heard readers stumble over unfamiliar words and get lost mid-sentence. Our hearts have gone out to readers who've been asked on their way in to church to read the Bible and been presented with a list of Hebrew names.

It doesn't have to be like that.

When Ezra the scribe read from the Book of the Law from daybreak to noon (Nehemiah 8:3), we're told that "all the people listened attentively".

The Levites "read from the Book of the Law of God, making it clear and giving the meaning so that the people could understand what was being read" – in other words, giving a running commentary.

Such was the power of the words that the people wept as they listened.

The actor David Suchet has recorded the entire New International Version, a staggering achievement praised for the quality of his rendition.

Very few people have his skills – but, he says, readers can improve. The key is preparation: "Prepare everything," he says. "Failure to prepare is to be prepared to fail. If you stand up to read in public you have to do what I did – find out who it was for, what it was for, look at the language, the punctuation, compare texts, compare translations – know what it is you're reading. Is there onomatopoeia? Is there alliteration or allegory? Is it poetry or prophecy?

"I was asked to read the story of the Annunciation in Salisbury Cathedral. I made so many notes that if you'd seen it you would hardly have been able to read the text."

He concludes: "Read it slowly, authoritatively and with confidence. It is the word of God."

Read with feeling, care and understanding, the words of the Bible are enormously powerful. Read hastily, in a way that's unprepared or slapdash, the words of the Bible are devalued.

Bible reading is part of worship. We should do it as well as we possibly can.

Guidelines to help churches get the best out of public Bible reading:

1. Take it seriously as a ministry. Invite people to audition.

2. Issue guidelines about how to prepare, encouraging people to spend time in study.

3. Let people have readings well in advance – and definitely not on the door!

4. Offer training and be prepared to pay professionals for it.

5. Be prepared to experiment, for instance with dramatised readings, but don't be gimmicky: it's the word of God.

Follow @RevMarkWoods on Twitter.