Religious people are happier, research claims – but how much does it matter?

Does religion work?

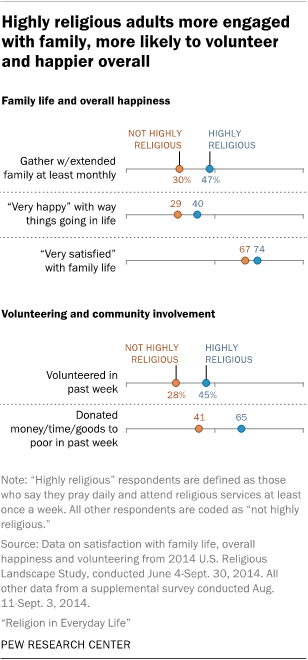

New findings from America's respected Pew Research Center appear to show that "people who are highly religious are more engaged with their extended families, more likely to volunteer, more involved in their communities and generally happier with the way things are going in their lives".

The 'happiness dividend' is quite striking, with 40 per cent of highly religious US adults describing themselves as "very happy" compared with only 29 per cent of those who are less religious.

That's settled then. If you want to be happy, go to church, pray and read your Bible. It won't guarantee happiness, but it'll improve your chances, so what's not to like?

Then, of course, we start interrogating the figures and we find things aren't as simple as that.

Figures like this are sometimes seized on by Christians anxious to prove that religion is good for the soul. Well, it can be, and we shouldn't be afraid to say so. Church is a school for the spirit. It makes us talk to people we wouldn't instinctively want to befriend, it provides a community of enquiry and support, it teaches us about patience, perseverance and loving kindess. It allows our gifts and personalities to blossom. It teaches us about God.

That's church at its best, and probably church at its average, too; most churches are OK. There are still too many that fall short and damage people horribly. Let's admit that too.

But let's not jump on these figures and claim they prove anything.

Maybe people aren't happy because they go to church. Perhaps they go to church because they're happy. These are naturally gregarious, unselfish, family-orientated people who find that a church community allows them to be themselves and encourages their sunny outlook on life.

And in other ways, the survey shows religious people aren't that different from everyone else. They're just as likely to lose their cool in stressful situations, to overeat, and to be indifferent about caring for the environment.

So it raises as many questions as it answers. One of these questions is about happiness. Is it a particularly useful measurement for Christians? Of course it's not a bad thing, but chasing happiness all too often means self-indulgence and pursuing short-term satisfaction. Lasting happiness is much more often a by-product of self-denial, discipline and commitment to a worthy goal. We can well believe that it comes from dedicated Christian discipleship, but it's not the point of Christian discipleship.

Another question is about unhappiness. It would be a misuse of statistics like this to treat them as an endorsement of happiness as the normal Christian state. That would be nice, and it may even, up to a point, be true. But not all Christians are happy. Some lead really difficult lives and struggle for all sorts of reasons. These people are gifts to the Church and just as much part of it as the happy ones. They shouldn't be regarded as failures.

The key question about Christianity isn't whether it 'works'. We can credibly claim that it does – that laws based on Christian principles make countries stronger and fairer, that Christian moral values make society work better, and even that Christians are happier. But the real question is whether it's true. Faced with the awesome reality of God made man, everything else is rather insignificant.