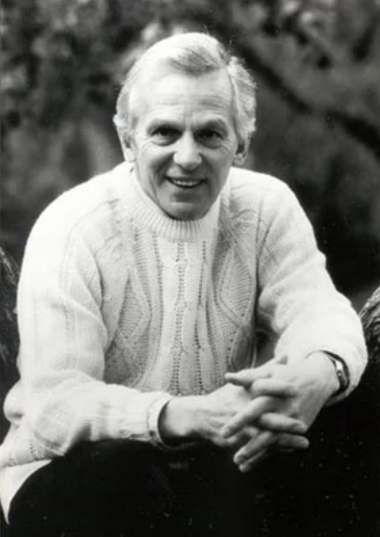

Remembering Brother Andrew, a fearless smuggler of Bibles

(RNS) — Depending on when you were born or what you believe, you may have never heard the best-known exploits of Andrew van der Bijl, who passed away on Tuesday. Many in the Christian world, however, know the work of the man known as Brother Andrew — even if they don't know they know it.

During the Cold War, Andrew, born in the Netherlands in 1928, operated like a Christian international spy, smuggling Bibles and Christian literature into communist Eastern Europe in the 1960s, coordinating the delivery of a million Bibles into China via a tugboat manned by 20 missionaries in the 1980s.

Open Doors, the organization Andrew founded in 1955 (and whose U.S. operation I now head), later delivered another million New Testaments in Russian to the Russian Orthodox Church.

These stories, some of which he told in his 1967 bestselling book "God's Smuggler," only scratch the surface of Andrew's adventurous personality and the contributions he made to the church.

But as someone who has inherited a share of Andrew's work, I can tell you that it was in his everyday life, away from all the media attention, that Andrew was perhaps the most inspiring.

My last visit with Andrew, on April 12, 2018, came days after my 50th birthday and only a month before Andrew's 90th. Andrew and I had met a number of times, but we both recognized this very likely would be the last time we would see each other this side of heaven.

The purpose of this visit, unlike previous ones, wasn't business. The only item on our agenda? To take a walk in his cherished garden at his home outside of Amsterdam. Despite a chilly day and overcast skies, he led me out to his rows of plants and magnolia trees, still beautiful though he'd had to give up tending them himself. It was, I thought, an apt metaphor for his relationship to the ministry he'd built, now carried on by others.

But a month later, he announced he would go to Pakistan. Andrew had spent much of his previous decades trying to show the love of Christ to Muslims. Now, violence was rising between some Muslim groups and their neighbors. Though Andrew knew it would be difficult, if not impossible, to get a meeting with the leader of the Taliban to talk about Jesus, he would not rest until he stood on Pakistani soil and tried.

No protests from others could change his mind, any more than they'd been able to talk Andrew out of such exploits in his 30s, 40s or 50s. Now, in the final stage of life — months after his wife had died — any naysayers likely had less chance than ever to talk him out of such ideas.

So Andrew got on a plane and flew 3,500 miles to an area contested by terrorists and extremists. He did not get to meet with the one Taliban leader he most wanted to see, but he did deliver his message from God. His trip still inspires me and many other to continue to carry love to our Muslim neighbors.

This historian's challenge is to accurately capture legendary heroes of the faith, like Andrew, who are often a paradoxical mix of stubborn, passionate strivers and gentle, compassionate souls. Andrew was also contrary, full of contradictions. He carried the most tender heart for the vulnerable; he could not bear it when Christians were cut off from access to the Bible. He could not stand silent and do nothing, knowing people around the world were persecuted for their faith.

But he was equally opinionated about the Western church; our camp drew his sharp criticism. It was difficult for a man who would risk meeting with Pakistani extremists to understand how those completely free to be part of a church or read their Bibles would not do so.

In his garden that day, after I finished telling him about all our team was doing to further Open Doors' mission, Andrew turned to face me, looked straight into my eyes, and said, "David, when you love the book, you invest in the book."

This statement was at the crux of it all. It was the motive and the answer to much of what Andrew did.

Andrew really believed what all Christians are supposed to: that the Bible changes people. It was his passionate love of Scripture that had transformed him from an injured war veteran to a champion of the global church. Andrew believed, unquestionably, that if he could get anyone — an extremist, a lazy American worshipper, a nonprofit CEO like myself — to keep reading the Bible and wrestling with Scripture, that our heads would clear and our hearts would chase what's right. Whatever wisdom and courage we needed would stir in us over time.

Andrew's other great subject was community — especially the global community of believers. This people-loving part of Andrew is what earned the nickname "Brother Andrew," a tag that stuck after someone observed how he committed to living as a brother to all.

Unlike some vigilantes who draw fame to themselves, Andrew refused to be a loner. He insisted, tirelessly, on working alongside others. He would often tell me, and others, "This is not a work you can do alone."

As a result, Andrew was always on the hunt for new rebels and radicals willing to go to the darkest places on earth, at the risk of death, to change the world. And he was grateful for everyone who joined his cause. "I'm blessed to be surrounded by so many good people," he frequently said.

These people were instrumental, he knew, because they would carry on his work in more places and times than he himself could carry it. Today, this is certainly true. Thanks to the work started by Andrew, Open Doors staff and partners work in more than 60 countries around the world ... and there is no shortage of vision for expanding into more.

With the passing of Brother Andrew, and Billy Graham before him, I can't help but feel like we have lost the final pieces of a great generation of Christian leaders. But as we search for inspiration in Brother Andrew's journey and the courage he showed in standing against totalitarian governments, extremists and religious infighting to serve those persecuted for their Christian faith, I think he'd waste no time in laying down a challenge:

The lessons from my life will be useless unless a new generation arises to carry the torch, to look for new and creative ways to take the Bible into places that are torn by war, hatred, nationalism and generations of conflict.

More than anything, Andrew would want the Western church to continue to support persecuted Christians around the world and support them in better and bigger ways.

As I wrapped up our visit and prepared to leave, Andrew started to say goodbye, then paused as if he'd thought of something better to say.

"Keep going," he said, his volume quiet but his conviction strong as ever. "Keep going."

It's not a work we can do alone.

David Curry is president and CEO of Open Doors USA, which advocates on behalf of those who are persecuted for their Christian faith throughout the world.

© Religion News Service