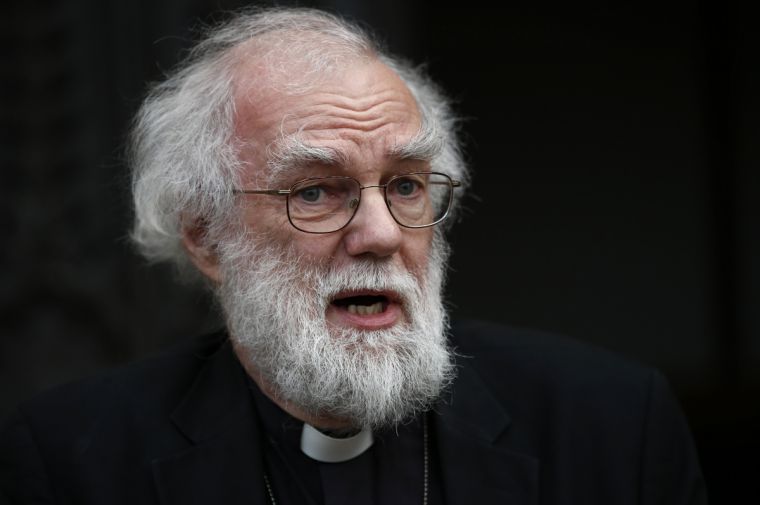

Rowan Williams: How theology helps us understand 'Being Human'

Rowan Williams, Master of Magdalene College, Cambridge and archbishop of Canterbury from 2002 until 2012, has produced a new book. Being Human will be published on March 15 by SPCK. This is an extract from that book.

[We] are in a cultural and work environment where it seems that individualist assumptions prevail, assumptions about control, assumptions about unavoidable conflict, assumptions about there being always a private area into which we can retreat and shut the doors...If we live in an uncooperative environment, if we've developed uncooperative selves, the field is not lost. Something can be reclaimed. But it can be reclaimed only by a careful, systematic challenge to those assumptions about what the human is that so imprison us – a challenge to our (in the broader sense) educational philosophies. That's a challenge that needs clarity about what a person is and isn't; clarity about the difference between the person and the mere individual; clarity about the capacity of human agents to do what my sources describe as transcending the merely natural, transcending the simple list of things that happen to be true about me.

Such clarity is not easily available either for a simply materialist view of human life – the human individual as a machine... – or for a purely spiritualist view of human life – human identity is just the sovereign iron will that lives somewhere in here and imposes itself on the world out there. Somewhere in between is an understanding of human identity, human personality, as fascinatingly and inescapably a hybrid reality: material, embedded in the material world, subject to the passage of time, and yet mysteriously able to respond to its environment so as to make a different environment; able to go beyond the agenda that is set, to reshape what is around; above all, committed to receiving and giving, to being dependent as well as independent, because that's what relation is. I am neither a machine nor a self-contained soul. I'm a person because I am spoken to, I'm attended to, and I'm spoken and attended and loved into actual existence. Which takes us back to the question of human dignity and the sacred, and to that pervasive, mysterious, nagging sense that there is always something about the other person that's to do with what I can't see and that can't be mastered.

But, finally, this is all a lot simpler than it sounds, because if we ask how we do, as a matter of fact, relate to one another, we may notice a number of things. We relate to one another as bodies. We notice that there is a fundamental bodily difference among human beings that has to do with gender, and we notice there's a fundamental bodily fact about us which is that our bodies wear out and that we're going to die. We talk to one another and we expect to listen to one another. We expect, in other words, relationship to evolve in language. We behave as if relationship mattered, as if we were not, in fact, capable of setting our own agenda for ever and a day. And when we encounter people who apparently don't behave like that we regard them as, to put it mildly, a bit problematic.

The question is, can we find a language for this simple everyday fact about us – that we speak and we listen, that we recognize our bodies and their difference and their vulnerability? Can we find a language for living that kind of life, because neither the 'machine' language nor the 'independent soul' language will do the job? We need a language of personhood. And Vladimir Lossky...was quite right to say that it's really very difficult to get a clear concept, even if we do know what we're talking about.

But that does land us with the final and, I find, rather appealing paradox. People quite often say that theology is about describing unreal relations between unreal subjects; Friedrich Nietzsche said it famously in the nineteenth century and many have said it since. But what I'm really suggesting is that when it comes to personal reality the language of theology is possibly the only way to speak well of our sense of who we are and what our humanity is like – to speak well of ourselves as expecting relationship, as expecting difference, as expecting death. (And, of course, for Christians and people in other faith traditions, expecting rather more than death as well – but that's perhaps for another occasion.)

What I want to leave you with is simply the sense that it is in turning away from an atomized, artificial notion of the self as simply setting its own agenda from inside towards that more fluid, more risky, but also more human discourse of the exchanges in relations in which we're involved, and grounding that on the basic theological insight that we are always already in advance spoken to, addressed and engaged with by that which is not the world and not ourselves. It's in that process that theology comes into its own.

Rowan Williams is Master of Magdalene College, Cambridge and was archbishop of Canterbury from 2002 until 2012. Being Human will be published on March 15 by SPCK. This extract is published with permission.

His other books include God With Us (2017), Being Disciples (2016), What Is Christianity? (2015), Meeting God in Paul (2015), Meeting God in Mark (2014)) and Being Christian (2014) – all published by SPCK.