Sufjan Stevens - Carrie & Lowell review

Rob Bell once said that Christian makes a great noun, but a poor adjective. Whatever you think about his views on Hell, sexuality or Oprah, you have to admit the man has a point. So often, people of faith rush to label things as 'Christian': films, books, music – even theme parks. Yet that use of a religious word to narrow the scope of God in culture only creates a sacred/secular divide that is, in John Stott's words, a heresy.

Perhaps that's why so many culturally-successful Christians choose to distance themselves from the label; not because they're ashamed, but because they find the phrase unnecessarily reductive. At last count, three quarters of U2 and half of Mumford of Sons were reported to profess faith in Christ – yet both bands are careful never to be saddled with that unhelpful prefix. Both however repeatedly explore Christian spiritual themes in their music, and are perhaps more free to do so – on a bigger canvas and to a wider audience – because they don't claim to be recording specifically religious albums.

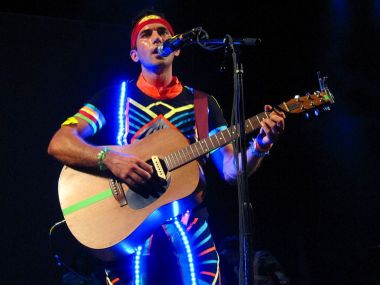

The same is undoubtedly true of Sufjan Stevens, darling of the Hipster movement and the auteur behind what's likely to be one of 2015's most 'Christian' albums (as it were). Carrie & Lowell, a sort-of concept album about the singer-songwriter's mother and step-father, is packed with references to faith, God and the Cross. It's not some sort of secretly evangelistic work however; as a committed follower of Jesus, Stevens is interested in every aspect of human existence – from death and grief (addressed in the first and several other tracks) to mystery and love. For Sufjan, these are the natural subjects you write about as a musician who is also a Christian. God is present – or sometimes feels painfully absent – in all of them.

There's no sacred-secular divide in sight, nor are there simple, fluffy statements of faith. Stevens writes powerfully about the wrestling nature of his spirituality, especially in grief. One haunting track, titled 'No Shade in the Shadow of the Cross' both acknowledges God's presence and the lack of comfort Stevens has felt from it. Another moment, in 'Drawn to the Blood', sees him identifying with a post-haircut Samson: "My prayer has always been love, what did I do to deserve this?" he laments. It's not the sort of sentiment you'll find being shared on some instragrammed cloud picture, but My Lord, it's real.

Carrie & Lowell sees Sufjan exploring his darkest moments, yet it's also a profoundly hopeful album. Even as he struggles with mother Carrie's death, he writes about grace ("I forgive you mother, I can hear you, and I long to be near you") and beauty ("My brother had a daughter; the beauty that she brings: illumination"). And by allowing us to join him on this very personal journey, in which he's the very antithesis of the smiling Christian who has all of life 'sorted', his faith becomes real; attractive, even.

Stevens recently told music blog DOA that aside from the Nashville production lines, "there's no such thing as Christian music." His implication of course is that God is present – and able to speak – through any song. That might be true, but he seems to shine more brightly through some than others. It's somewhat ironic, but Sufjan's gritty journey through his personal darkness ends up bleeding divine light.

Martin Saunders is a Contributing Editor for Christian Today and an author, screenwriter and the Deputy CEO of Youthscape. You can follow him on Twitter: @martinsaunders