The churches and the aid agencies made the same theological error

There's a certain irony about the timing of the report of the House of Commons' International Development Committee (IDC) report into aid agencies' record on sexual exploitation and abuse.

It is damning, accusing them of 'complacency verging on complicity'. Aid workers – those heroes of our time – used prostitutes in disaster-hit areas who were desperate for cash, traded food for sex, abused children – you name it, they were at it, and their employing organisations did very little to stop them.

No, OF COURSE not all of them. Of course a tiny minority, and of course most aid workers are as pure as the driven snow – including, and we may hope especially, the ones who work for Christian organisations. But as the IDC report says: 'No corner of the aid sector appears to be immune: the problem is a collective one.' It quotes Kevin Watkins, chief executive of Save the Children UK, who says: 'This is not the occasional bad apple that we are dealing with here; it is a structural and systemic problem that we have to deal with through proper integration.'

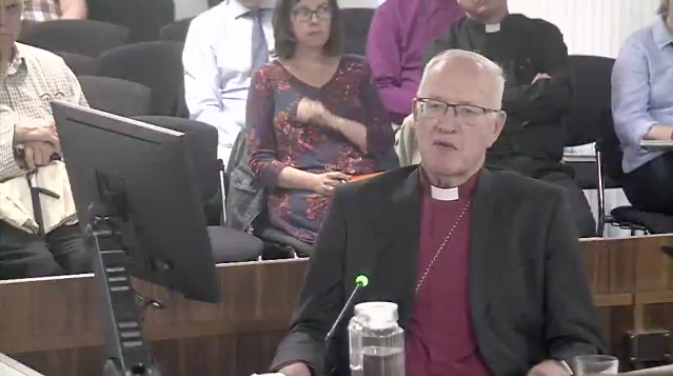

The irony, of course, lies in the temporal proximity of the IDC report to the skin-crawling, toe-curling embarrassment of the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse review of the Church of England's handling of the Peter Ball case last week. At the heart this was the testimony of former archbishop George Carey, whose personal failures contributed so much to Ball's evasion of justice for so long.

It also coincides with the resignations of the Australian Archbishop Philip Wilson, convicted of covering up child sex abuse in his diocese, and US Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, accused among other things of sexually assaulting a teenager 50 years ago. The saga of the Chilean bishops continues to run. And among US evangelicals, the Southern Baptists are still dealing with the fallout of their own #MeToo moment.

However, there's more than irony here. There are points of comparison between the world of aid agencies and the world of the church that are rather instructive.

Both rely on the support – the admiration, in fact – of the wider public. They have it, at an institutional level, because they are there when people need them. And aside from this, they are both represented, at the sharp end of their work, by people who are prepared to make themselves vulnerable, to take risks, to devote themselves to a cause, often for little financial reward. Their motives – yes, those of the clergy too – are, in the fullest sense, humanitarian.

Because of this, they come with a considerable amount of moral capital. We assume they're good people because they're doing a good thing.

And put like that, the cracks in our edifice of assumptions start to show. Why on earth should we think that? There are very few people, after all, whose goodness runs all the way through them. Most of us are not sticks of Blackpool rock. We are fractured, damaged, at best complicated, a kaleidoscope of motives and desires. The same person is capable of enormous goodness and self-sacrifice, and abysmal failures and betrayals. 'With the tongue we praise our Lord and Father, and with it we curse men, who have been made in God's likeness,' says James (3:9), an astute observer of human nature.

Well: the IDC report says of scandals among aid agencies, 'outrage is appropriate but surprise is not'. It's exactly the same with the church. And the shock that's greeted the revelations of clergy sexual abuse is because the church – as both institutions and individuals – has failed to grasp something fundamental about theological anthropology.

George Carey told IICSA that he 'could not believe that a bishop in the Church of England could do such evil things'.

Of course he could. Lots of people could, bishops among them. Admitting this should not be hard for a Christian who believes, as most do, that there is a fundamental flaw in human nature that requires a Redeemer to fix. The number of those who would do such evil things – who, if they had that desire, would overcome moral conditioning, their fear of being found out and their fear of God – is far fewer. But the potential for serious wrongdoing is there in all of us.

It's the failure to acknowledge this that has led us – the church, the aid agencies, the administrators of orphanages and child migrant schemes and all the rest – to where we are today. We have bought into the 'hero' myth – 'Because this person is doing good things, they'll never do anything bad.' It's an idea powerful in its romantic simplicity and toxic in its foolish naivety.

Are we then living in an age where unqualified admiration is simply no longer possible, and we are automatically suspicious of everyone? I hope not. But the failure of institutions affects more than the immediate victims. Their function is also to safeguard honourable people. They are there to protect the reputation of the good – or mainly good – by mercilessly excising the bad. Institutions, including the church, are there as defenders of hope. They are a bulwark against cynicism, making it possible for us still to believe.

And when they fail to do that, because they lose their moral clarity, or in the case of the church, fail the most basic theological test, the damage is incalculable. For the aid agencies, it's a dent in donations; they'll bounce back in a few months. For the church it's far worse: recovery will take years, if not decades, and the casualties of faith along the way are heartbreaking to think of.

The church at the moment is living in an age of shame. Its institutions have let down its individuals. It has to prove it understands that before it can begin to regain the capital it has lost.

Follow Mark Woods on Twitter: @RevMarkWoods