The enduring legacy of St Columba

The writer of the Letter to the Hebrews reminds Christians that they are surrounded by a great "cloud of witnesses." (NRSV) That "cloud" has continued to grow in size since then. In this monthly column we will be thinking about some of the people and events, over the past 2000 years, that have helped make up this "cloud." People and events that have helped build the community of the Christian church as it exists today.

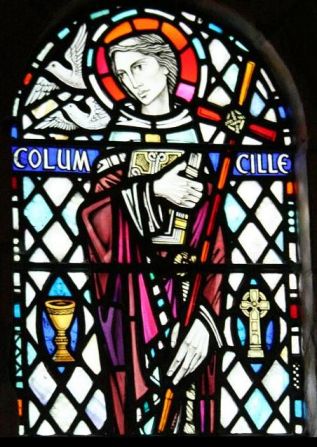

On 7th December AD 521, a young Gaelic (Irish) woman named Eithne, who lived in north-west Ireland, gave birth to a baby boy. Traditionally, this occurred at Gartan, in what is today County Donegal in the Irish Republic. Eithne and her husband, Fedelmid, were nobles, members of the Irish elite. They named the little boy 'Colum Cille' in Gaelic. It meant 'the dove of the church.' He was to become better known to history by the Latin form of this name: Columba.

Some Irish sources claim that his name was 'Crimthann' (meaning 'fox'). It is possible that he was originally called this but adopted the name 'Colum Cille' later in life. On the other hand, the two names may reflect different verdicts on the man. As he shall see, his life was not without controversy.

But what kind of world had baby Colum Cille/Columba/Crimthann been born into?

The British Isles in the sixth century

To describe the political state of the British Isles in the sixth century as 'complex' is something of an understatement.

The island of Ireland at Columba's birth was a mosaic of kingdoms that had never been part of the Roman Empire. Its most powerful dynasty – the Ui Neill – later had Columba's cousin as its overking. Christian missionaries had been active in Ireland during the fifth century. The most famous of these was the British Christian, Patrick, but he was not the first. As druidic traditions retreated in the face of the Christian advance, Ireland became famous for its Christian learning. By the sixth century, a number of monasteries had been established, which would later play a major part in Irish faith and culture, and beyond.

What is now England and Wales did not exist at the time of Columba's birth. The British provinces of Rome south of Hadrian's Wall had drifted out of imperial control around 410 and in the years between then and Columba's birth had fragmented into warring kingdoms. By the mid-sixth century most of the central, southern and eastern areas had come under the control of Germanic rulers (later termed Anglo-Saxons); although the level of incoming migration from the continent varied from area to area.

From this melting pot of cultures, the competing Anglo-Saxon kingdoms were beginning to emerge. While Christian minorities almost certainly continued to exist in these areas, a pagan culture had replaced the (officially) Christian culture of Late Roman Britain. In the north-eastern part of this area the kingdom of Northumbria would eventually emerge out of the rival Germanic kingdoms of Deira and Bernicia. It would, one day, interact significantly with the legacy of Columba and those who followed him.

In the west, a chain of independent British kingdoms held their ground in a line that stretched from the Dorset coast right up to what is now Cumbria and southern Scotland. Speaking the British language (which would one day develop into Welsh) they considered themselves the inheritors of Roman civilization. They were officially Christian. There was bitter and ongoing warfare between them and their Germanic rivals to the east.

What we now call Scotland did not exist either. And getting our heads around this is particularly important, because it would be the focus of Columba's missionary activity. North of Hadrian's Wall, what had once been clients of Rome were now independent British kingdoms. Those in the east of this region were losing ground to the Germanic rulers of Bernicia.

North of a line, roughly drawn between the Firths of Forth and Clyde, the lands were contested between the Picts and the Scots. Both played a major part in Columba's story. The Gaelic-speaking Scots (originally from Ireland) ruled the kingdom of Dal Riata (or Dalriada). At its height, Dal Riata encompassed the western coast of what is now Scotland and the north-eastern corner of Ireland. In Columba's day, it covered what is now Argyll (meaning 'Coast of the Gaels') in Scotland, and part of County Antrim in what is now Northern Ireland. Along with other Gaelic (Irish) communities, they had converted to Christianity.

The Picts were a group of peoples who lived in what is now northern and eastern Scotland. We think they spoke a form of the British language. They first emerge in Roman records in the third century, out of the various tribes of unconquered Caledonia. When Columba was born they were still pagan.

This is the backdrop against which Columba lived and acted.

The backstory of a saint

Columba's later biographer – Adomnan, the ninth abbot of Iona, writing in 697 – tells how the little boy was fostered by a priest to be educated. It was common practice for Christian noble families to give small children to the church, to be raised for a life as a priest, monk or nun. In the same way, elite households also fostered other family's children as a way of building secular alliances.

Ordained as a priest, but living a monastic life, he founded several monasteries in Ireland. This may have included the monastery at Kells, which became famous for its Christian learning.

A turning point occurred in the year 563, following the battle of Cul Dreimhne (also known as the 'Battle of the Book'). One tradition insists that this occurred due to a dispute over the ownership of a manuscript that Columba had copied. This seems a rather extreme way to settle a copyright issue! However, it probably illustrates the way in which patronage of rival religious communities, by different elite Irish families, had become another way in which power-politics played out in early medieval Ireland.

In the end, Columba left Ireland as "a pilgrim for Christ." There is some debate over how voluntary this exile was. What is beyond doubt is the dramatic effects of his move.

Columba and Iona – church on the 'sea highway'

On leaving Ireland, Columba travelled to the court of the Scots ruler of Dal Riata at Dunadd, which survives today as a hillfort in modern Argyll and Bute. As a result, the Scots king granted Columba the island of Iona on which to found a monastery. This was certainly the tradition known to Adomnan. Another tradition, recorded by the eighth-century Anglo-Saxon monk Bede, was that the king of the Picts gave the land to Columba following his conversion to Christianity.

Modern visitors to Iona will be struck by the isolated peace and solitude of the site. Nothing could be further from how the location operated at the time of Columba. Situation on the main sea-route down the western coast of Scotland it was more a 'church by a motorway,' than a 'hermitage in the wilds.' Columba's saintliness and the learning of the community drew visitors from far and wide. So much so, that Columba often had to withdraw to a quieter place for undisturbed prayer. He used a stone as a pillow, like Jacob at Bethel in Genesis.

Missionary trailblazer...and battler of monsters!

Soon other Christian communities were founded on nearby islands, imitating the way of life on Iona. Iona became the mother-house of a family of religious communities in Scotland, Ireland and, in time, in England.

From Iona, Columba crossed the mountains of central Scotland to preach the good news of Christ to the pagan Picts. Later traditions recalled his miracles of healing; slaying a ferocious wild boar with a word of command; baptising far and wide; besting pagan priests; at one time he was preceded by a pillar of fire (like Israel in the wilderness); and protected by angels.

Adomnan records that, at the river Ness, Columba saved his servant from a fierce water-beast that had previously killed a man in the river. This seems to be the first appearance of a beast that would later be known as the 'Loch Ness Monster.'

The impact of Iona

It is hard to exaggerate the impact of the community that Columba founded at Iona. It became a spiritual, cultural, and intellectual powerhouse. Later traditions indicate that by the year of Columba's death, in 597, Christianity had been preached across the Pictish lands, and in every island along its west coast. Even if this exaggerates Columba's impact on the Pictish kingdom (other missionaries were also active there), it was still an extraordinary achievement.

In the next century, Iona had so prospered that its abbot, Adomnan, wrote in fine Latin the 'Life of St Columba,' which is a major source on his origins, life and achievements. From Iona more Christian missionaries went south, most famously the Irish Aidan and his Irish companions, to preach the Good News in newly minted Anglo-Saxon kingdoms as far apart as Northumbria, Mercia, and Essex.

So great was the sanctity of Columba that it was claimed that, after his death, he appeared in a dream to the Anglo-Saxon King Oswald of Northumbria, promising him victory before the Battle of Heavenfield (c.634). What is certain is that Oswald had earlier been a political exile in Dal Riata and had converted to Christianity there. Victorious in battle, he called on monks from Iona to preach the Christian message in his kingdom and settle on the island of Lindisfarne. This would soon become another spiritual powerhouse – this time in northern England.

Even Viking raids, after 795, could not eclipse Iona. Relics of Columba remained there and when Viking rulers converted to Christianity, they came as pilgrims to the monastery that earlier Vikings had attacked. A number of Gaelic-Norse kings would be buried there. The cross of Christ had triumphed over the hammer of Thor.

The year that Columba died (in 597), an official Christian missionary group sent from Rome by the pope arrived in the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Kent. In the next century there would be considerable tensions between the church practices established by this venture and those that emanated from Iona, and which were also found in the British kingdoms. In the end it would be the 'Roman' ones that triumphed. However, this should not cause us to lose sight of the huge contribution made by Gaelic-speaking Christians (in the tradition of Columba) to the emerging Christianity of Anglo-Saxon England.

The importance of Columba today

Columba was no 'plaster saint.' He was embroiled in Irish ecclesiastical politics and was possibly exiled; big and tough, he could be fiery too; yet he was also gentle and caring; a counsellor to visitors and the confidant of kings. He was both 'Colum Cille' (the dove of the church) and 'Crimthann' (the resourceful and feisty fox). Dedicated to Christ, he brought the gospel to pagan peoples, accompanied by miracles. He established religious communities that would carry on the work after him. His actions – personally and through these – had a huge impact on the culture of many early medieval kingdoms in the north and beyond.

Happy 1,500th birthday, St Columba!

Martyn Whittock is an evangelical and a Licensed Lay Minister in the Church of England. As an historian and author, or co-author, of fifty-four books, his work covers a wide range of historical and theological themes. In addition, as a commentator and columnist, he has written for a number of print and online news platforms; has been interviewed on radio shows exploring the interaction of faith and politics; and appeared on Sky News discussing political events in the USA. His most recent books include: Trump and the Puritans (2020), The Secret History of Soviet Russia's Police State (2020), Daughters of Eve (2021), Jesus the Unauthorized Biography (2021), The End Times, Again? (2021) and The Story of the Cross (2021). He also has an interest in early medieval history and the world of Columba, having written The Origins of England, 410-600 (1986), A Brief Guide to Celtic Myths and Legends (2013) and a number of books on Viking history, most recently The Vikings: From Odin to Christ (2018) co-authored with his eldest daughter.