Theocracy: Did a leading theologian call for a Christian caliphate?

There are certain words that have almost nuclear potential in an argument. If you use them – and particularly if you accuse the other side of being responsible for one of them – you're making a very bold call.

'Theocracy' is one of these words. It conjures up images of terrifying religious leaders controlling the status quo. Their arbitrary power is used to persecute minorities, quash opposition and make life miserable for everyone.

In historical terms maybe we think of Oliver Cromwell's joyless protestant rule over England, or indeed Bloody Mary's Catholic reign of terror.

Perhaps our minds drift to the present, where the Iranian regime headed by Shia spiritual leader Ayotollah Khameini has executed over 700 people this year alone – or their Sunni rivals in Saudi Arabia, where beheadings and even crucifixion are carried out as punishments for simply exercising free speech.

With this in mind, surely no sensible Christian theologian or apologist would suggest that Christians in the 21st Century should be seeking a theocracy?

But that's just what one of the world's leading New Testament scholars, Tom Wright, did this week.

Wright, the former Bishop of Durham and now on the staff of St Andrew's University, used part of an address at St Paul's Cathedral to suggest that Jesus came to inaugurate a 'cruciform theocracy' here on earth.

It's an argument Wright has developed across several of his academic and popular books – that Jesus' life, death and resurrection isn't primarily about personal salvation for Christians or about us going to heaven when we die. Instead, says Wright, there is a richer story to tell. That, as he put it this week, "[Jesus] was not preaching a new 'religion' nor was he telling people the secret of how to get to heaven after he died. Not about how we can get to heaven, but about how heaven's rule can come to earth. Not just a protest movement, although there is a new energy and sense of direction for a good deal of protest. Nor just a way of reordering a private mentality, although will indeed turn you upside down, some of which will be comforting, some will be very uncomfortable. He came to institute God's rule on earth, theocracy."

This is a bold, exciting and inspiring vision of the coming Kingdom of God. Wright's signature eschatology (his theory of what will happen at the end of time) has begun to have a radical effect especially on evangelical churches on both sides of the Pond. No longer is environmentalism seen as a waste of time if the earth will be renewed by God, not destroyed. No longer can churches simply worry about preaching that which 'gets people to heaven.' Instead they're called to be part of the coming of God's Kingdom in the here and now through mercy and justice as well as evangelism.

But that one little word from Wright's address still sticks out. If 'theocracy' is almost universally regarded as a bad thing, why would Wright be advocating it as God's plan?

It strikes me that Wright is mounting a deliberate campaign here. He has spent his career trying to get Christians to take their faith, the Bible and the Gospel seriously – and engage with what orthodox Christianity really teaches, rather than what they hazily imagine. So here he wants us to engage with what he actually means by 'theocracy' rather than just relying on the first stereotype that comes to mind when we hear the word. He's agitating us to think differently about a concept that we've been led to believe is a very bad thing indeed.

But, surely theocracy is a bad thing? Well, maybe that depends on your definition of God. If your god is bitter, vengeful and violent, then certainly, theocracy doesn't look like a good idea. In fact, it looks pretty much like life under fundamentalist militants like Islamic State. But if your definition of God is of loving relationship, self-sacrifice and the ultimate victory of good over evil, then it's a different matter.

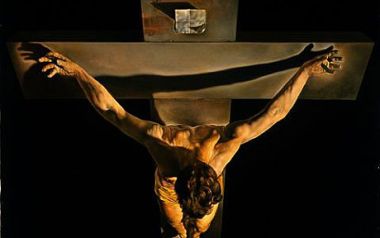

That's why it's important we engage with the qualifying words Wright used to describe the kind of theocracy he was suggesting Jesus is inaugurating. He said, "The Gospels tell the story of how the cross wins the victory of the kingdom, the messianic kingdom. Of how the kingdom came and comes not like the manner of earthly kingdoms but in a different way altogether," before suggesting this means a, "cruciform theocracy."

In other words Wright is talking about a kingdom which is based not on domination, violence and oppression, but instead based on the Jesus we see revealed on the cross – offering himself fully for the human race, the world and indeed for the redemption of all creation.

This nuanced reading of Wright's message wasn't what the National Secular Society had in mind when reporting on the St Paul's event. In a blog posted the day after, the NSS' campaigns manager, Stephen Evans said, "I'm sure most Christians in the UK would join us in dismissing these bizarre comments. Theocracy and the imposition of religious belief through coercion is the direct cause of many conflicts in the world today; to say nothing of the immense human rights abuses that theocracies perpetuate."

But here's the thing. Wright didn't call for "the imposition of religious beliefs through coercion." In fact, by advocating a 'cruciform theocracy' Wright is doing the exact opposite. Jesus allowed himself to be put to death by people who so violently disagreed with him that they tortured and killed him. Repeatedly through scripture we read of opportunities he had to impose his will on others, but he allowed them a free choice.

As author Donald Miller puts it, "In the story of the rich young ruler, Jesus asked him to follow Him, to join Him, to develop a relationship on His terms. The rich young ruler declined, as we know, and Jesus stood and grieved because He loved the young man. And then Jesus walked away."

This couldn't be further removed from the accusation of the, "imposition of religious belief through coercion."

Of course theocracy conjures up horrific images for us, and not without good reason. No-one is advocating a return to the Inquisition, or even to the days when being anything but an Anglican would see you deemed a second class citizen. But a welcoming of the rule and reign of the servant king? That's something I can get on board with. As Tom Wright himself put it this week, "We with the gospels have... a story, but it is a love story, not a power story." Amen.