There's no gospel without God's justice

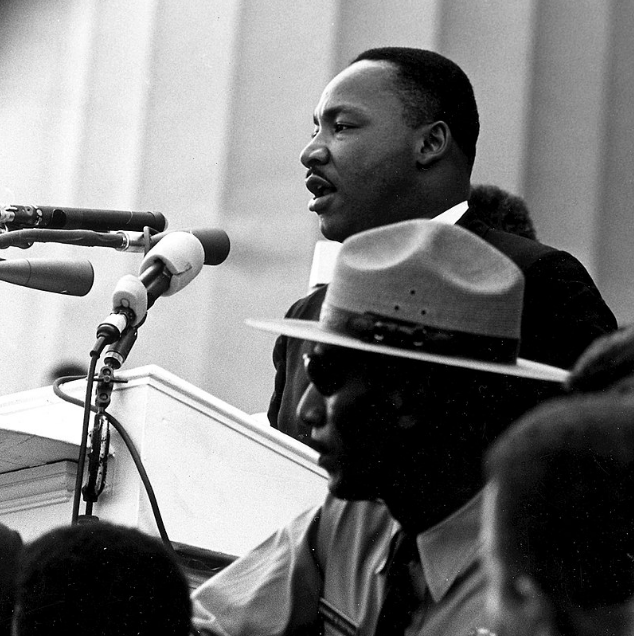

I was recently reminded of a sermon Dr Martin Luther King Jr delivered at a church in Brooklyn, New York, in 1966. The sermon's title was Guidelines for the Constructive Church, and Dr King's text was Luke 4:18-19:

The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me

to proclaim good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim liberty to the captives

and recovering of sight to the blind,

to set at liberty those who are oppressed,

to proclaim the year of the Lord's favour.

'This is the role of the church: to free people,' Dr King said. When we set people free – from spiritual, emotional, physical, social or economic bondage – we proclaim the acceptable year of the Lord, as the KJV translation says.

'The acceptable year of the Lord is that year that is acceptable to God, because it fulfills the demands of his kingdom,' King said. 'The year of the Lord is not some distant tomorrow, which is beyond history, but the year of the Lord is any year that men decide to do right.'

If asked to find a verse that summarizes the gospel, I suspect most Christians would make a beeline to John 3:16. Yet Luke 4:18-19 – which Jesus read out of Isaiah in the synagogue of his hometown Nazareth – is as much a gospel proclamation as the most famous verse in the Bible. In fact, this passage might be the first time Jesus preached the gospel of the Kingdom of God.

Now, at this point someone might say, that's not the gospel – what about Jesus' death, burial and resurrection? What about sin and forgiveness, heaven and hell? Without a doubt the gospel story is incomplete without them. But I would venture to ask: what exactly is the gospel, this good news?

If we take a long look at the narrative of the New Testament (and Old Testament), we quickly find one unavoidable assertion: Jesus is King and Lord of all, and he has come to put all things right in Creation. That is the scandalous message of the gospel. It's the claim that got him crucified. Jesus is greater than Caesar or any other ruler on Earth; he is the promised Messiah of Israel; he is God made flesh. His life, death and resurrection, the miracles he performed, the prophecies that spoke of his coming, all give witness to his kingship, lordship and saviourhood.

The coming of the rightful King is indeed good news for the poor, the captive, the blind and the oppressed because it signifies the coming of justice and reconciliation. Jesus' kingdom doesn't look like the ones here on earth, which are too often built upon the backs of the weakest members of society. In his kingdom, the power structures of the world are upside-down: the poor are rich, the captive are free, the blind can see and the oppressed are strong. So, when Jesus healed the sick, welcomed the outcasts, blessed the poor and forgave sinners, he wasn't simply performing signs. He was showing us what life in God's Kingdom looks like, including what it means to have our Imago-Dei (God-image) restored.

We know from Scripture that though it's not fully here yet, God's Kingdom is already in our midst (Luke 17:21). We live in the in-between: praying, 'Your kingdom come, your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven' (Matt 6:10) and living as if 'our citizenship is in heaven' (Phil 3:20).

This is the full vision of the gospel of Jesus, but over time many Christians have forgotten it.

Today in many churches in the West, the gospel has been reduced to a formula to get to heaven (or to avoid going to hell). We forget the Protestant Reformation occurred within a specific context. It was imperative for Martin Luther to debunk the false doctrine of works-based salvation – the sale of indulgences to the poor masses was in itself a case of spiritual injustice – and to recover the doctrine of salvation by grace, through faith alone.

But this truth is only one of the dynamic pieces of the gospel, not the whole picture. Jesus died on the cross to redeem not just our souls but our entire humanity: mind, body and soul. His bodily resurrection shows us that God's justice and compassion work not exclusively in the spiritual realm but in every sphere of existence.

When we give preeminence to the spiritual aspect of the gospel alone we not only miss out on the fullness of God's kingdom, but we also inadvertently damage our witness for Jesus. Why should present-day oppression and injustice matter if our goal is to get souls to heaven? Reasoning like this has allowed the church to ignore and even participate in some of the most egregious miscarriages of justice in history. We would be remiss if we forget that the apartheid in South Africa, the segregation of blacks in America and the Holocaust all took place in nations with Christian majorities.

This isn't a problem exclusive to the Western church. In India, my home country, the church has struggled to overcome casteism – India's version of racial discrimination. Though outlawed, the caste system and its dehumanizing view of a person's value based on the purity of their birth still permeate Indian society. In its failure to fully repudiate casteism, the church has greatly damaged its witness to the millions of Indians from low castes who have been brainwashed to believe they are not created equal.

I am the first to admit this is a hard pill to swallow. But we cannot continue turning a blind eye to issues of injustice if we are going to be effective in witnessing to the transformative power of the gospel of Jesus – the messenger has to be credible if the message is to be believed.

We also need to realise we can cannot pave over our checkered history with charity. Our acts of kindness, no matter how generous, ring hollow if we have not learned to speak against all forms of injustice.

And we must remember that when Jesus tells us to seek first God's Kingdom and his righteousness, he is calling us to live in justice (the Greek root word dikaiosune has both meanings). Only then can we become the constructive church Dr King envisioned — a church that can preach the full gospel of the Kingdom of God to a world yearning for good news.

Most Rev Joseph D'Souza is an internationally renowned human and civil rights activist. He is the founder of Dignity Freedom Network, an organization that advocates for and delivers humanitarian aid to the marginalised and outcastes of South Asia. He is archbishop of the Anglican Good Shepherd Church of India and serves as the president of the All India Christian Council.