True biblical holiness: It's not about what you don't do

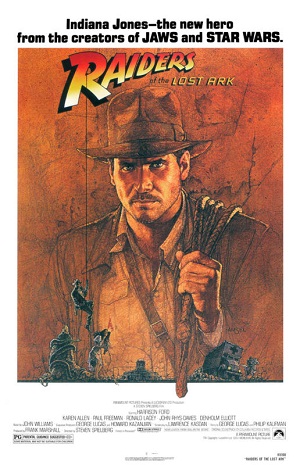

At the end of the film Raiders of the Lost Ark there's one of those iconic moments. The evil Nazis have succeeded in locating the lost Ark of the Covenant ("It's a transmitter for talking to God!") and are unwise enough to take the lid off.

If you're one of the very few who haven't seen it, no spoilers here other than to say it doesn't end well.

It's pure hokum, obviously. But think about the idea behind it. There's something in that box which is too pure, and too dangerous, for human beings to look upon.

The same idea is expressed in Exodus 33:21-23, when God hides Moses in the cleft of a rock and hides him while his "glory" passes by, so that he sees only his back. It's there in 2 Samuel 6:7, when Uzzah puts out his hand to steady the ark when it rocks on its cart; God strikes him dead.

God is radically different. God is dangerous. God is holy.

And this idea of holiness runs all the way through scripture. At its root is the idea of being separated. Sometimes this means that things are completely destroyed, like the Amalekites in I Samuel 15. Other things are not designed for common use, like the Temple and its furniture. Objects – and people – can become contaminated and need to be purified. The whole race of Hebrews is 'holy', separated from those around them, and intermarriage between them is forbidden – see Ezra 10 and the tragic story of those who have taken foreign wives being required to divorce them.

In the New Testament, holiness takes on dimension. "Just as he who called you is holy, so be holy in all you do; for it is written: 'Be holy, because I am holy'" (1 Peter 1:15-16, quoting Leviticus 11).

But what's New Testament holiness about? Not, in spite of the Leviticus quote, separating yourself from anything that might cause ritual contamination. Instead, Jesus turns holiness on its head. It isn't about keeping yourself free from taint by making sure that avoid anything that could compromise you. It's an active movement of love and compassion towards another person. It's a personal commitment to do good things, no matter what they cost.

The old ritual holiness laws looked a lot like the anti-infection measures hospitals put in place to control outbreaks of disease. But citizens of the new Kingdom of God deliberately go out and infect people with grace.

That's why Jesus healed people on the Sabbath, even though it was technically forbidden (you were allowed to stop people getting worse, but not to do anything to make them better). The parable of the Good Samaritan turns on the purity laws: the priest and the Levite didn't want to touch the man lying injured by the roadside because he might have been dead. They wouldn't have been able to worship in the Temple because they'd have been ritually unclean. For Jesus, that isn't holiness, it's hypocrisy.

We sing about holiness all the time. We dwell on the holiness of God, by which we often mean something uncomfortably like that whole Raiders of the Lost Ark thing.

We pray to be made holy. But I'm not sure that we really understand what we mean by that.

Holiness, in the minds of many people, is about what we don't do. It's about not drinking too much, or not drinking at all. Christians aren't supposed to gamble, have sex before marriage, lie, cheat or steal. We're supposed to have more integrity than other people.

In the New Testament Church, these were all issues: read Acts, or Paul's letters to Timothy, and you can see them grappling with things that were new and strange ideas for just-converted Christians.

But Jesus made holiness about what you did do, not about what you stopped doing. All these things are important, but none of them are radical. None of them change the world.

For Jesus, being holy means encountering individuals nice, saved people would normally run a mile from. For him, being a friend of tax collectors and sinners didn't compromise his holiness, it was the essence of his holiness.

Should we be careful what we say and what we do, and be sure that we're not bringing the name of Jesus into disrepute? Of course. But religion that's all about keeping our noses clean has nothing to do with Jesus.

He said, "I have come that they may have life, and have it to the full" (John 10:10).

So here's what that might look like.

1. People who live full, abundant lives aren't scared of getting things wrong. In his letter to the Colossians, Paul criticises legalistic Christians: "Why, as though you still belonged to the world, do you submit to its rules: 'Do not handle! Do not taste! Do not touch!'?" (Colossians 2: 20-21). They're relying on rules to keep them from doing the wrong thing, instead of relying on God to help them do the right thing. Holy Christians are found among people who are not respectable.

2. People who live abundant lives don't spend all their time in church. The mark of a Christian who's still living by the rules rather than by grace is that they need walls around them to make them feel safe. But you don't have to spend all your time going to Christian meetings, seeing Christian friends and doing 'Christian' things. That's old-school thinking, as though you're holier when you're separate from 'the world'. Jesus-type holiness is being different in the world.

3. People who live abundant lives are evangelistic even when they don't talk about God, because they make him interesting. There's a stereotype – fed, it has to be said, by Christians who've led narrow, cramped and joyless lives and seem to want to recruit others to do the same – that being a Christian is all about what you give up. But that's not what Jesus says. Being a Christian is about living every day intensely and being full of curiosity about the world and our place in it. When most people's horizons are limited to the things of this world, that's holy.

4. People who live abundant lives are focused on God first, and only second on the world that he's made. Yes, holiness in the new Kingdom Jesus brought is directed outwards, towards other people, rather than inwards at making sure we don't offend. But it must always be anchored in faith in God. "We love, because he first loved us," says John (1John 4:19). Love that's cut loose from its moorings will drift. Holiness in the world is only possible because of our relationship to a holy God.

Holiness is about separation. It means we're different. But that difference isn't expressed in keeping the world at arm's length, it's expressed in embracing the world in the love of Christ.

Follow @RevMarkWoods on Twitter.