Ursula Le Guin: What the atheist writer taught this Christian

One of the frustrating things about the way many Christians argue against atheists is how they often project their own worries on to people who just don't see it it that way. One of these worries is around the meaning of life: 'If you don't believe in God, life fundamentally has no meaning.' It's meant as an argument – 'Therefore you should believe in God.'

It isn't really an argument; the fact that proposition A might be unpalatable doesn't necessarily mean you should accept proposition B. But the other problem with it is that it doesn't pay respectful attention to what atheists might actually think about life, death and the lack of a hereafter.

A few years ago I was interviewed for a UK Christian TV station. One of the questions the interviewer asked was about which books had influenced me. I think I threw him by talking about Ursula Le Guin's Earthsea trilogy.

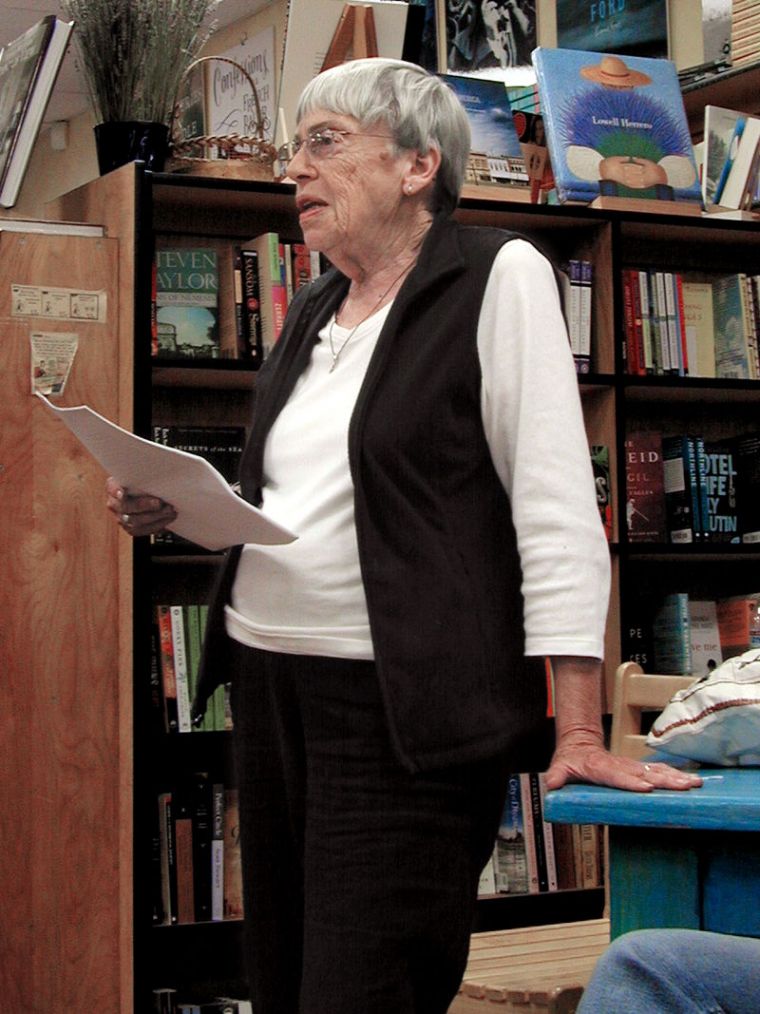

Le Guin, who has died aged 88, was a hugely respected and creative science fiction writer whose work influenced not just others in the genre but seriously literary types as well, including Salman Rushdie and David Mitchell. She won every award going. She was phenomenally well read, and her interests included anthropology, sociology, gender and environmentalism.

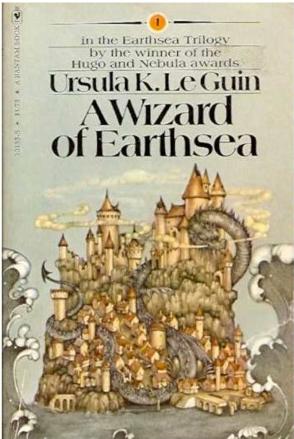

And Le Guin was an atheist, whose Earthsea trilogy – about a wizard named Ged and his battles with the various powers of darkness – amounts to a full-scale assault on what she perceived as religion's destructive preoccupation with living forever.

As fiction, it's absolutely perfect. It's rich, humorous, moving and wise. You are immersed in a world that's completely believable though extraordinarily strange. Magic happens through words, through which gifted people exercise power. But it's perilous, too, because it can be misused.

In the first book, A Wizard of Earthsea, Ged is forced to confront a 'shadow' loosed when he attempts to conjure the dead. A villager asks him, 'What of death?' '"For a word to be spoken," Ged answered slowly, "there must be silence. Before and after."'

In the Earthsea trilogy there is a place of the dead, but it's a place of shadows. No one knows each other, no one speaks – and it's this to which everyone must come.

The epigraph to the first book is a poem:

Only in silence the word,

Only in dark the light,

Only in dying life:

Bright the hawk's flight

On the empty sky.

It's the transience of life and action that gives them meaning. The silence, dark and dying are essential if the word is to be heard, the light is to shine and the life is to be lived.

In the final book, The Farthest Shore, all this becomes much more explicit. Another wizard, Cob, has become terrified of dying and has broken the springs of magic so he can be repeatedly resurrected. Thousands share his fear. There's violence and social breakdown. Many use drugs to try to follow him. Ged defeats Cob at the cost of his own magical powers. People can die properly again, and because of this the richness and harmony of life in Earthsea is restored.

(I should say, by the way, that I'm speaking of the original trilogy – 1968-73 – because she returned to the Earthsea world decades later, in 1990 and subsequently. There's a sense of being preached about gender politics which is a bit irksome; she does this much better in The Left Hand of Darkness, another classic. She also introduced different ideas about death, which I found artistically unconvincing. So I'm sticking with the original.)

Why, then, did I shock my Christian interviewer by choosing the Earthsea trilogy rather than, say, the Narnia books? According to Le Guin, the Christian eternal life is a destructive fantasy that leaches all the colour and meaning out of life. Best to accept that you're going to die and that after a while no one will remember you. Do the best you can while you're alive, because there's nothing else but extinction.

Now, that is not actually what I believe, because I'm a Christian (mind you, it echoes Ecclesiastes in all sorts of ways). But it taught me two things. One is about the enormous value of the life we have been given. Religion should never make life less – less happy, less rich, less fulfilling. It should never make people worse – less merciful, less gracious, less generous. Its teaching about an eternal life should never justify us not making this one as good as we can for as many as we can.

The other is that I saw clearly, as a Christian, that atheists can live meaningfully without God, in terms that make sense to them and are not inherently foolish. That's what the storyteller's gifts can do, and why all Christians should read good fiction: it makes you see the world through other people's eyes. Do I think they're right? No; I'd love to convince them otherwise. But I don't think I can do that by rubbishing their beliefs or assuming they just haven't thought things through.

Arguing with someone is rarely a good approach to converting them. But if we do that, we owe them the respect of understanding them first.

I'm grateful for Ursula Le Guin and her (as I believe) God-given gifts. She's one of those bright spirits who enriched the world.

Follow Mark Woods on Twitter: @RevMarkWoods