What was the main driver of the thousands of Ebola deaths in West Africa?

Global heath experts are once again on their toes as another Ebola outbreak has been declared in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), the number of suspected cases of Ebola has risen to over 43 from nine in less than two weeks in an isolated part of the DRC, where three people have died from the disease since April 22.

The last outbreak in West Africa killed more than 11,300 people across four countries. Now, Ebola appears to be back, bringing with it arguments, recriminations, accusations and counter-accusations of whether the right decisions and choices are made when outbreaks erupt.

Three years ago, Sierra Leone closed its borders with Guinea and Liberia on June 11 in a bid to stop the epidemic. However, a country-wide emergency was not declared until August: 6 months later. But it's a mistake to believe that the delay in an emergency response was the main driver behind the thousands of infections and deaths that were recorded across West Africa.

As a recent study entitled Protecting the Living, Honouring the Dead attests, cultural insensitivity to local burial practices, was the main driver fuelling the high rate of Ebola infections in most communities.

Almost all of the bereaved families we interviewed who lost relatives between May and November 2014 did not appreciate burials done by the early burial teams across the districts covered. 71 per cent of families who lost someone in the first six months of the crisis reportedly did not witness the burial of their relatives, and only 19 per cent were involved in the burial in some way.

We decided to tackle the issue by training people to handle and bury the dead in a way a cultural sensitive way. We trained burial workers – many of whom were survivors themselves – to observe religious and cultural funeral practices.

I've worked on the West African Ebola emergency response from the early outbreak in 2014 up to the present day, and it is a mistake to place blame solely on delayed action. As aid workers suspected, and now this report confirms, it was the failure to respect traditional burial customs - and wider ignorance of the virus - that contributed to thousands of Ebola deaths in Sierra Leone.

I hope that the latest outbreak of Ebola in northern DRC will remain 'isolated, remote, and small'. The location of the affected area appears to have helped contain the spread of the virus. Hopefully the Congolese health authorities have it under control. This is their fourth Ebola outbreak in 15 years. They seem to understand the virus and have a good track record on containment.

The situation in Sierra Leone in 2014 could not have been more different. Nobody had heard of Ebola. And when people started to die locals believed that it was witchcraft, government lies or anything but the fatal infectious virus that scientists and NGOs were talking about.

The arrival of burial teams clad in head to toe in white overalls, goggles and face masks struck fear into the minds of Sierra Leoneans. In the early days of the epidemic, burial workers gathered bodies without a thought for traditional funeral practices. Bodies were piled high and disposed of as efficiently as possible. There were no ceremonial dressings of the deceased or last goodbyes. No wonder then that around 96% of the families we spoke to were unhappy that prayer, washing, dressing and perfuming of bodies were not part of the process.

It's no surprise then that families started to hide the bodies of loved ones and bury them secretly. The consequence was that infection rates and deaths shot up.

The families we spoke to told us that the use of black bags and chlorine to wash corpses of their loved ones instead of shrouds were 'disrespectful and undignified'.

One bereaved parent told us how burial workers had 'dropped the corpse of my late child on the ground as though it was a bag of cassava. I also saw corpses rolled with sticks; others tied on ropes and dragged on the ground. It was such a painful and sorrowful scene that no one would be happy to see and talk about.'

Another issue that was overlooked was the cultural taboo of men burying women. It wasn't until our safe burial teams involved women and the wider family in the funerary process that we saw a shift in behaviour change.

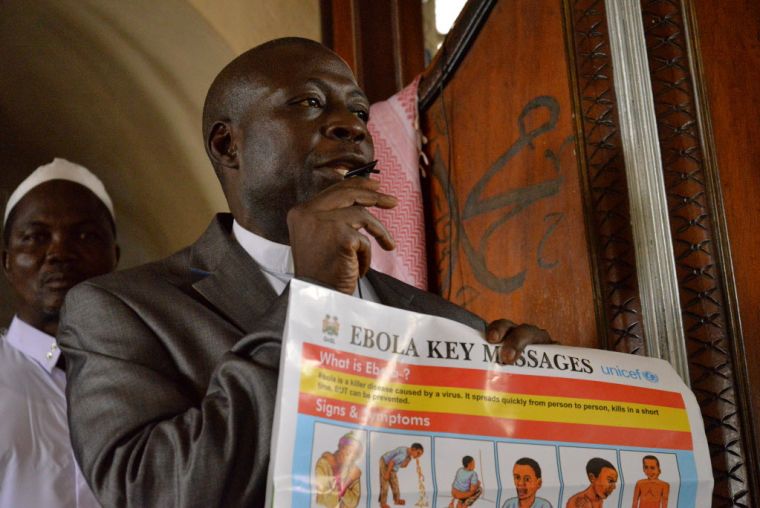

Involving religious leaders made a huge difference to our Ebola emergency response. Interestingly 100 per cent of all bereaved families agreed that the involvement of religious leaders and women in the burial process was very important. The mobilization of priests and imams to spread prevention messages saw infection rates plummet. And in the month after the Safe and Dignified burials were introduced the highest number of deaths were reported since the outbreak started.

Ultimately, the culturally sensitive approach to the response was key to the containment of the Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone. Wherever this virus strikes next, first responders must engage faith leaders, women and the wider community to stop Ebola in its tracks.

Caroline Iliffe is Emergency Programme Officer at World Vision. Follow on Twitter @worldvision